HOW ASKING SOPHIA LOREN 8 QUESTIONS ON HER 90TH BIRTHDAY TAUGHT ME TO LET GO OF AMERICA

NOTES ON CARING TOO MUCH AND THEN CONVINCING MYSELF NOT TO CARE. AND GRACE. SOPHIA TAUGHT ME ABOUT GRACE.

(Above: Photo of Sophia Loren by Tony Vaccaro. 1959.)

I was sitting with a friend, Richard Nahem, last night during the intermission of Hello, Dolly! at the Lido here in Paris on Avenue des Champs-Élysées (I will write about the production in my PARIS NEWSLETTER on Friday) and we were talking about our writing careers, this Substack column, his blog I Prefer Paris. He asked me if I still kept busy writing celebrity profiles and cover stories. I told him I barely do them anymore unless one considers my rather infrequent now FIVE QUESTIONS FOR … columns here at SES/SUMS IT UP in the same genre which are to me but distant cousins of the cover stories I wrote for Vanity Fair and myriad other magazines for around 30 years. “I do some profiles for the upstate New York magazine The Mountains which I enjoy doing,” I said. “And I recently was asked to do a Q and A with Sophia Loren for Grazia to celebrate her 90th birthday. I came up with the concept 9 Questions for her 90th but she only wanted to answer 8 of them. I’ll do celebrity profiles when someone reaches out and asks, but I don’t chase them anymore. I don’t pitch. It’s thought of as a young person’s job - writing those profiles. That part of my life is mostly over, as is being a young person.”

I went on to explain that when I actually do write a magazine profile that I put all my care and thought into the first draft and then - unlike for almost all my career - I let it go and seldom even read an edit anymore. “I once debated every disputed comma and fought to keep sentences in that meant a lot to me. I cared,” I said. “Well, I still care as I write the first draft. But I’ve learned to let them do whatever they want to do once I’ve cared. I just take the money off the bedside table now. I never thought I wouldn’t care, but I just don’t anymore. I have Substack where I concentrate so much of my writing; I care there. And I’m thinking about doing a third book which would be about my life as a pilgrim.”

I told Richard that the story about Sophia Loren was an assigned one. Surprised me. Came out of the blue. She wouldn’t, however, see me in person nor would she agree to do it by Zoom. The questions had to be submitted by email and she would then return the answers. I said I had never done an “interview,” if it could even be considered such a thing, under such circumstances and would only accept the assignment if I could figure out a way to do it by creating a new construct for it. And I did. I came up with one. I decided to write small pieces before each question submitted so that she herself understood the construct and maybe it would nudge her a bit into being less concise and more discursive since I didn’t have the chance so ask follow-up questions in such an emailed format nor to engage conversationally which is my preferred way to conduct an interview by not really conducting one.

The word count ended up being twice as long as what was assigned so it had to be cut by half. I always write to the length the piece demands and then worry about the cuts later hoping that more space will be found to run the story I have written. But the cuts had to be made for this story and the construct I had conjured for it was completely discarded and the whole thing was refashioned into an old-fashioned intro followed by the series of questions. I still haven’t read the edited version. I just assume it’s no longer in my voice. But I am deeply grateful for the assignment and the money left on the bedside table.

As I told Richard about all that last night, it dawned on me that in my putting all the care in these stories in their first drafts and then letting them go that I had developed the distancing technique that I am now applying to America and my decision not to return there for a long time as I keep my pilgrim’s life centered here in Europe and North Africa. America is now the comma in the sentence I no longer care about. It’s been edited away and I find myself not fighting to retain it. I will miss its punctuation but the subject of my life and the predicate for it now are here, not there. I am still working through the loss, the grief, the not caring part because I have so deeply cared about America and its politics all my life. But America feels like the edit of my story I don’t even have the desire to read. America for me now is Sophia Loren in fewer words. It’s no longer my voice.

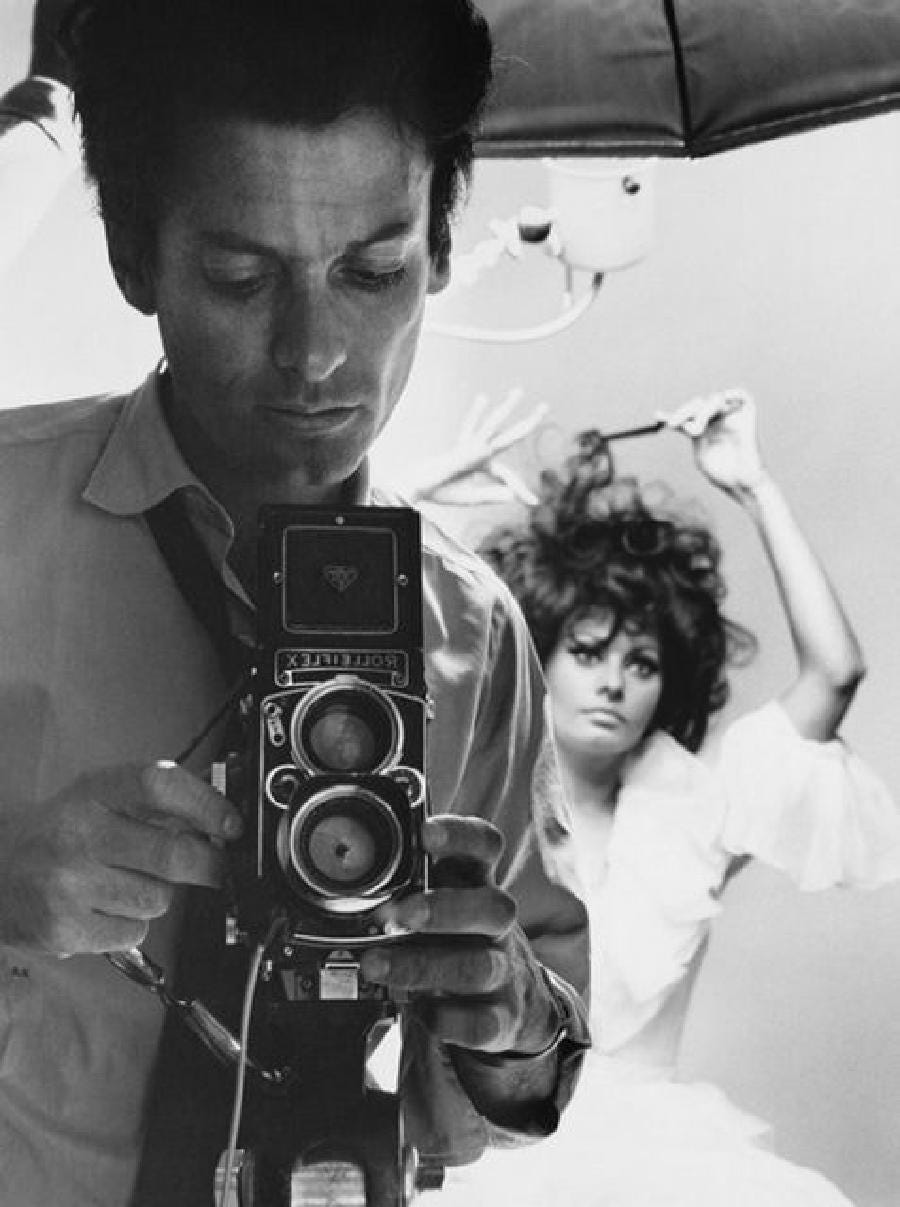

(Above: Richard Avedon and Sophia Loren. 1961.)

(Above: Loren photographed by Avedon. 1961.)

Here is that first draft. I put a lot of care into it.

EIGHT QUESTIONS FOR SOPHIA LOREN

#1: GRACE

I spent a month in Santa Fe this summer. One of my favorite galleries in town is the Monroe Gallery of Photography. Its show while I was there highlighted the work of Tony Vaccaro, who died at the age of 100 in 2023. The Vacarro show was titled “The Pursuit of Beauty” and featured not only his war photography which has an aching, brutal beauty all its own, but also his fashion work as well as portraits of Picasso, de Kooning, Pollock, Givenchy, O’Keefe, Peggy Guggenheim, Gwen Verdon, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Eartha Kitt. There was one portrait however that haunted me and to which I returned repeatedly during my stay there. It was of Sophia Loren taken in 1959.

Vacarro, who relished the capturing of a candid offhanded moment, caught the legendary movie star in a velvety-lips-apart, fingers-in-hair one, her eyes gazing back at the collective gaze she was just beginning to endure by being, even then, so calm and collected within it. There has always been a shyness to Loren’s shimmering movie star-ness, but she has never been demure which would be rather dumb of her to feign when so many of us still fall at her feet. At the same time, she has also been too keenly self-possessed and even kind to dare us to look away from her beauty that has always shone like headlights - hell, klieg lights - into our oh-dear, deer-like eyes.

And then there is the talent to which such beauty is tethered. In 1962, she won the Oscar for Best Actress for her bravura performance as the mother in Vittorio De Sica’s deeply moving Two Women after having wowed the audiences at Cannes the year before. The story centered on Loren’s maternal character trying to protect her young daughter as well as herself from the ravages of the Marocchinate, the term used for the mass rape and killings committed during World War II after the Battle of Monte Cassino in Italy. She was riveting as she attempted to relinquish her beauty but it instead bore more deeply into her until it became the ballast for both her and us to be able to brave, in turn, her bravery in taking on such a role that was both tender, tenaciously so, and yet unrelenting in the the brutality she had to suffer. “De Sica was an actor, and his way of directing other actors was to show them what he wanted," Loren once told The New York Times. “Instead of telling the scene, he was acting it for you. He did that for everybody, from the old lady to the sexy woman to the little kid. It was really a sight to see.”

Loren’s own singular talent as an actress - always a sight to see - was a melding of all three of those aspects of her humanity. As a young woman who became known as a sex symbol worthy of an Oscar there was always an old soul submerged beneath the sensuality, a canny ethereality which seduced us as much as the earthly, earthy beauty with which she is blessed. As an older actress there is embedded within her mining of characters and scenes the memory we share with her of her younger self, not a yearning to return to it but an appreciation of the longing she could engender within us as we, her audience, then mine that either ore of both those Lorens, the lionized and the lioness. And yet coupled with it all - the soulful wisdom, the bounty of her beauty, the revered artistic veteran - is the narrative of her childhood and her illegitimate birth, her poverty, her fortitude, which can soften us in both respect and empathy - just as it conversely toughened her - as we continue to find ourselves in her cultural presence in 2024, this woman with no need to preen but instead to present herself to us, plainly and forthrightly, in the service of her craft, her art, her life’s missions of acting and her own motherhood and remaining, yes, calm in that collective gaze we still bestow upon her. We still project our needs onto her image. And she still now at 90 graces us with her grace in allowing us to do so.

QUESTION NUMBER ONE

What is the source of such grace you have always been able to summon in order to navigate your life - privately and publicly - which has been both difficult at times and yet so blessed? Could you speak to the power of grace in all its manifested forms because when I think of you I think of that first and foremost: grace.

Grace comes from understanding yourself to the point where you are comfortable with every part of you. Grace comes from being at peace with who you are and that peace or self-serenity ripples out and touches others in the form of grace. Because grace is really balance. Balance doesn’t mean that you don’t also try to better yourself but it does mean that you are not defined by your insecurities, you are defined by acceptance and the desire to look at all parts of you and work on them with patience and empathy, not anxiety and despair. The good news about turning 90 is that you don’t have time for negativity and unbaked ego led emotions anymore, those naturally fall by the wayside leaving you to focus on what matters, on what makes you happy, whatever that may be. Even happiness frankly is not my main objective, what I try to pursue is peace and serenity. Happiness is often as transient as fireworks but peace and serenity can last a lifetime.

###

#2 OBJECTIFICATION

According to Tony Vaccaro, Loren was scheduled to come to his New York penthouse back in 1959 for an early photoshoot at 11 a.m. But around 10 a.m. the doorbell rang as Tony was just getting out of the shower. He assumed it was his doorman bringing him, as usual, The New York Times. So running from the shower, he wrapped a small towel around his hips to cover himself up. But when he opened the door, there stood Sophia Loren. She slowly looked him up and down, then said "Tony Vaccaro: always ready.”

Sophia Loren: always ready also.

QUESTION NUMBER TWO

Vaccaro insisted he innocently stood in that towel before you but many men with whom you’ve dealt in your life as a movie star in show business were, I assume, not so innocent. How have you dealt with being objectified as a sex symbol and did such objectification morph and alter over time since your stardom has spanned many cultural and societal changes? You have said, “You have to be born a sex symbol. You don’t become one. If you’re born with it, you’ll have it even when you’re 100 years old.” Could you speak as well to being a sex symbol still at 90?

First of all the term “sex symbol” has always made me somewhat uncomfortable. I am not naïve, I understand why I would be called a sex symbol, but it is such a minute part of me, or such a thin layer of who I am that I can’t help but not give it any true weight. And maybe that’s why I am a sex symbol, because I don’t care to be one and that insouciance or the fact that I don’t take it seriously is sexy. If you rely on your looks too much, not only people feel it but also you rely on something that is a fake friend, a false ally because eventually whether you like it or not “aesthetic beauty”, the one born from without, will inevitably desert you and then, what are you left with if that’s all you counted on, if that was the only source of your strength? Beauty might be the front door to a person, or the front façade of a person, it could be the reason why people give you the time of day at first but then once the person has walked in through the front door, beauty disappears and what people respond to is who you are inside, behind the front façade. That’s what matters, the beauty inside, it’s a cliché because it’s true. And that beauty is not as homogenized as the outer one, that beauty shines the brightest according to how unique and emotionally rich it is. Being grounded has also a lot to do with it. Being grounded makes you open and accessible to all sorts of people, which in turn makes you all the richer humanly and this kind of beauty is ageless and timeless. In fact, it improves with age.

###

#3 DIRECTORS AND PHOTOGRAPHERS

From Vittorio De Sica (Two Women, The Gold of Naples, Marriage Italian Style, Sunflower, Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow) to Edoardo Ponti (The Life Ahead, Between Strangers, Human Voice) from Arthur Hiller (Man of La Mancha) to Rob Marshall, (Nine), from Robert Altman (Ready to Wear) to Stanley Donen (Arabesque), from Michael Curtiz (A Breath of Scandal) to Sidney Lumet (That Kind of Woman), from Martin Ritt (The Black Orchid) to Carol Reed (The Key), from Stanley Kramer (The Pride and the Passion) to Delbert Mann (Desire Under the Elms), from Ettore Scola (A Special Day) to Charlie Chaplin (A Countess from Hong Kong), Loren has worked with some of the greatest film directors and been photographed by our greatest photographers, including, in addition to Vaccaro, Herb Ritts, Richard Avedon, and Alfred Eisenstaedt. Chaplin told her, “I feel that, when I direct you, I am the director of an orchestra.” She adored him, as she did “Eisie,” as she called Eisenstaedt who photographed her for seven Life magazine covers throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Ritts photographed her for the 1995 Vanity Fair Hollywood edition which put her in its category, “The Goddess.” The editors there also referred to her as a “force of nature.” She is.

(Above: Loren photographed by Eisenstadt. 1961.)

QUESTION NUMBER THREE

Chaplin said you were like conducting an orchestra. With which instrument do you most identify and why? Also, would you like to talk about any of your directors regarding those with whom you adored working, like Chaplin, as well as those with whom you found it more difficult to deal? In addition, do you like being photographed? Some actors don’t. They don’t consider themselves models although Pauline Kael once wrote about you - she was a fan of yours as much as a critic: “Wouldn’t we rather watch [Loren] than better actresses because she’s so incredibly charming and because she’s probably the greatest model the world has ever known?” Do you consider that a compliment or just a backhanded one, even from a fan?

My mother was a concert pianist, my son Carlo is a conductor whose specialty instrument is piano, so I would say that I relate to piano the most because it is the closest thing to an orchestra. It can be used for a solo as much as part of an orchestra. I like that. When I act, even if I am the protagonist of a film, I don’t see myself as the “lead”, I see myself as part of a team, part of an orchestra. Yes, I might the “first violin” or the “featured pianist” but always in relation to a greater ecosystem. I am at the service of my character, of the story, of the director.

The director that taught me everything I know, that helped me “unlock” whatever it is I had inside so the camera could capture it is Vittorio De Sica. He was and still is my mentor. When I work, I can still hear his voice whispering directions in my ear, I can still feel his gaze upon me full of encouragement and paternal love. I drew so much courage and bravery from that gaze, that gaze made me who I am today.

Do I like being photographed? It depends on the day. Sometimes I do, sometimes I don’t. Being photographed is exactly the opposite of acting. When you act, your job is to react to everything around you, every moment calls for a different emotional colour. Being a model is to hone in on the colour the photographer is seeking and when you find it, freeze in that moment until the photographer tells you to shift. So really, being a model and being an actor are two opposite things.

###

#4 KINDNESS

A decade ago, Vivian Rothstein wrote an article titled “What I Learned from Sophia Loren” at the website for Capital & Main. “When I was 13 I was, like many kids growing up in L.A., offered a bit part in a movie,” Rothstein remembered. “But this wasn’t any movie; this was Desire Under the Elms, starring Sophia Loren, Burl Ives and Anthony Perkins. Written as play by Eugene O’Neill, its story was so risqué that my mother wouldn’t let me see the film for years. (Young and beautiful Sophia Loren is married to old man Burl Ives but has a child by his slightly creepy son, Tony Perkins, while they’re all living together on an isolated farm.) …

“There wasn’t anything glamorous about Burl Ives repeating his lines a million times and pretending to dance with me and the other two kids as if he were having fun at a farmhouse picnic. Ives never said a word to me or the other girl from my ballet school who was hired because she also ‘looked like a farm kid.’

“What saved it all for me was Sophia Loren, who breezed into the studio every day with her glowing smile, greeting each one of us individually, starting with us lowly extras and working through the whole crew before she got down to work. She had something personal to say to each of us. Her attention raised our status and got us talking to each other. …

“Loren was recently quoted in the Los Angeles Times as saying, at a Screen Actors Guild award event, ‘I’m just a little girl from Napoli. I can’t believe I am here with all these famous people.’ That’s how she acted on our set. And we all fell in love with her.

“Loren … was honored in L.A. last week by the American Film Institute, which paid tribute to her 50 years of stellar work in U.S. and European films.” Rothstein continued. “If you’ve seen her movies you’ll notice her stunning physicality and beauty (I’m sure shown to best effect by the camera crews who, like me, appreciated her respect and acknowledgement). And watching her act, one also sees the connection she conveys with people who are poor and struggling. ‘You know,’ the Times quoted her as saying, ‘I was raised during the war and the only thing we dreamed about was to make it through the next day.’

“Brava Sophia Loren for your life’s work! And thank you for all you taught me.”

QUESTION NUMBER FOUR

I was so struck by the your kindness in this story. How has kindness played a part in your life? Do you remember anyone intersecting with your life as you did with this young girl during the making of that film and unexpectedly teaching you a lesson that has stayed with you ever since?

Kindness is everything. It’s what every relationship should be based on because kindness is not just kindness, when you are kind to someone, it also means that you respect them, that you see them, that you acknowledge every layer of who they are. Kindness is essential to me maybe because I grew up in a time during the second world war when kindness was replaced by vitriol and bombs, but underneath the rubble, in the basement and tunnels where he hid from the attacks, there was a lot of kindness. That kindness shown to us by our neighbours, or the stranger huddled next to us waiting for the sirens to stop, or the family relative. That brand of kindness is what kept us safe and sane. I want everyone to feel that kindness.

###

#5 LEADING MEN

Loren has written about kindness before when she was writing about men in her memoir, Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow: My Life. “I have my own peculiar yardstick for measuring a man: Does he have the courage to cry in a moment of grief?” she wrote. “Does he have the compassion not to hunt an animal? In his relationship with a woman, is he gentle? Real manliness is nurtured in kindness and gentleness, which I associate with intelligence, comprehension, tolerance, justice, education, and high morality. If only men realized how easy it is to open a woman's heart with kindness, and how many women close their hearts to the assaults of the Don Juans.”

Sophia Loren has starred opposite many dashing and handsome leading men - among them Paul Newman, Gregory Peck, Jean-Paul Belmondo, Cary Grant, Frank Sinatra, Marlon Brando, Charlton Heston, Daniel Day Lewis, and Marcello Mastroianni. But it is Anthony Perkins with whom she costarred in Desire Under the Elms and Five Miles to Midnight that most fascinates me. He fascinated her also and I read that she even attended his funeral in 1992 after he died from complications from AIDS. At his death a statement was released which Perkins had prepared: “I chose not to go public about [having AIDS] because, to misquote Casablanca, 'I'm not much good at being noble,' but it doesn't take much to see that the problems of one old actor don't amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world. I have learned more about love, selflessness and human understanding from the people I have met in this great adventure in the world of AIDS than I ever did in the cutthroat, competitive world in which I spent my life.”

QUESTION NUMBER FIVE

I appeared as Alan Strang in Equus with Tony Perkins when he played Dr. Dysart. His son Elvis has become a dear friend of mine. So I have a personal connection to this question. What are your memories of dear Tony? And, in his memory, what has taught you the most about love and selflessness and human understanding?

I remember Tony as a very generous actor, thoughtful and open. I loved looking into his eyes, he had such a rich enigmatic inner life. He was able to shift so effortlessly and so quickly from light to darkness, from goodness to mystery. It was incredible to behold. Being an actor really means to be a reactor to whatever your scene partner throws your way and that means being a good listener. Tony was an amazing scene partner because he was so present and responsive. What he taught me was to remind me to listen.

###

[TO READ THE LAST THREE QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS PLEASE CONSIDER BECOMING A PART OF OUR PAID SUBSCRIBER COMMUNITY FOR ONLY $5 A MONTH OR $50 A YEAR. THANKS.]