LETTER FROM LONDON: 2/14/25

Mickalene Thomas, Much Ado About Desire, Asa Butterfield, A Cameo by Gillian Anderson, and Everything Is Not Beautiful at the Ballet Because It Is Everything (That's Its Beauty)

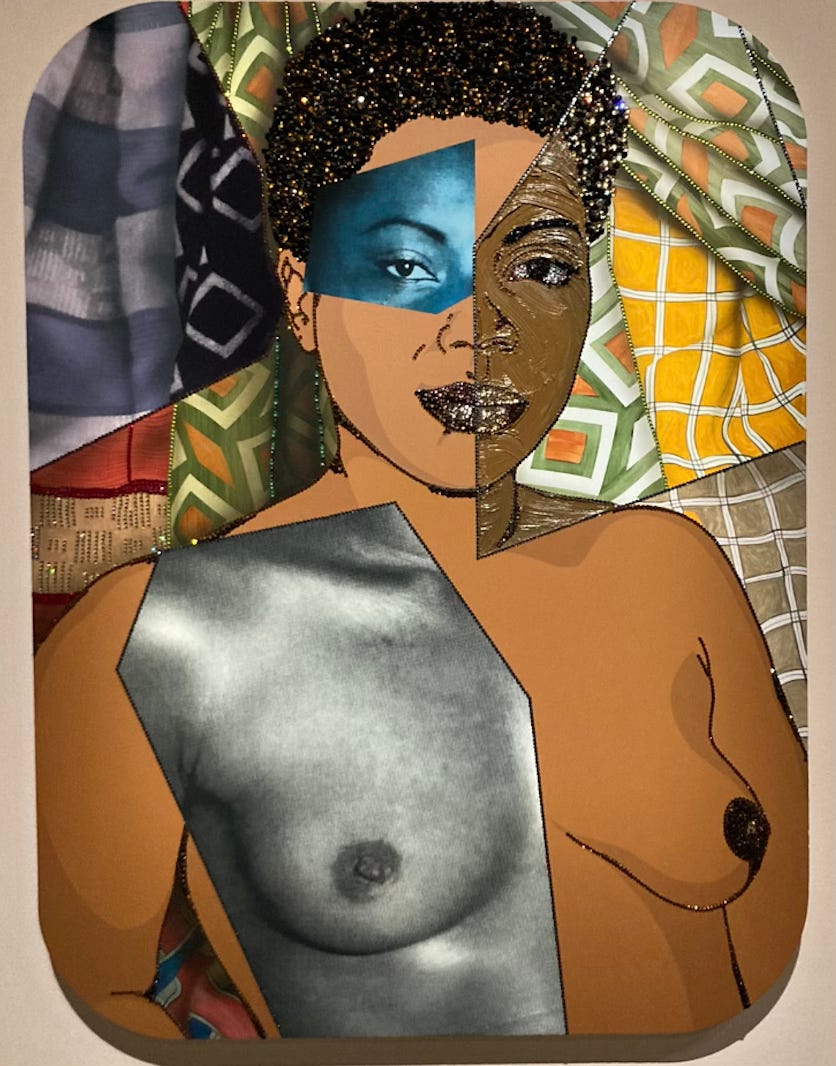

(Above: One of the first works you encounter at Mickalene Thomas’s remarkable show at the Hayward Gallery, “All About Love,” which reminded me of another work, the one below by Andy Warhol of Marsha P. Johnson in his “Ladies and Gentleman” series.)

“Desire is always this strong feeling of longing,” claimed Mickalene Thomas when she was in a conversation back in 2021 with Thelma Golden, the Director and Chief Curator of The Studio Museum in Harlem. “It’s the desire of our histories, it’s the desire of my ancestors and the other generations before me, it’s the desire of having us be seen in the same way as that idealized beauty. It’s the desire to understand your own resilience in the world. I bring forth in my work those notions of women loving women, the desire for us to see ourselves, the desire of queerness, the desire to say, ‘Yes, I’m a queer Black woman who loves other queer Black women.’ I examine my own self and question my own sense of self through my love and the desire of women, not only in relation to the historical images but also to the relationships regarding the systematic oppression of Black women that we ignore in society. When I think in those terms, I don’t necessarily want to always deal with the trauma. We all have trauma, we all have a story that derives from that trauma.

“The desire is to inspire. Thinking about what my mother has endured in her physical self, being this 6’1″ woman who all her life battled with sickle cell anemia and all her life had to struggle with her health, and yet has always presented her best self, standing tall and strong and letting the world know that she exists. Seeing that desire within her to live, and to love, has instilled in me the desire to celebrate life.”

Golden: “It’s a real act of resistance.”

Thomas: “And rebellion.”

Golden: “And recognition.”

I have often stated since I settled deep into the decade of my 60s that I no longer have desire so much, but I do have a deeper sense of longing. Mickalene Thomas conflates the two in her conversation with Golden above and in the sweeping retrospective of her work now up at the Hayward Gallery which runs until May 5th. I visited the show on Wednesday morning and will return before I leave for Porto on April 2nd. I was not only moved by how blatant she is in depicting her longing and desire for the Black female body but also how in that blatancy it can almost become blasé - a kind of political posture itself that has nothing to do with posturing but instead the ease and comfort of the radical repose - especially if you blow through the exhibit and don’t settle into it like one does into the decades of one’s life because there is a sense of that as well in the show. We dwell, as we stroll though it all, within the installations that reference the artist’s 1970s childhood where the aesthetics of longing become the desired return to the furniture of home - hers and our own remembered rooms - which exist alongside her art school years and now into the present which sees her having such a timely show on the banks of the Thames in London. I hope she desired such a show in her longing for recognition within the art world that broadens the kind of recognition - bristles even a bit at it - which Golden references above. Because we need it all right now - resistance, recognition, rebellion, resilience, even more than a bit of bristling - in this world where Black bodies and female bodies and LGBTQ bodies are being politically targeted by Trump and others like him who revel in their demonization of them, of us. Thomas’s art is not only resplendent in the many collages of carnality there on the varied surfaces of the work but also in the deeper and durable human need to see clearly and thus be seen, a clarion call that lands like a thunder clap in the midst of the gathering storm in which we all now live. I marveled at the show’s range and variety - video, photographs, installations, collages, painting - and was grateful for its daring presence in such a dangerous time.

But we lowly humans (who long for the desirous exaltation) have always lived in dangerous times. The day after A Streetcar Named Desire opened on Broadway on December 3, 1947, the third of the Nuremberg Trials came to a close and 10 of the 15 jurists on trial were found guilty. Much Ado About Nothing is thought to have been written around 1599 when in what is now New Mexico the Acoma Massacre took place instigated by Spanish conquistadors which resulted in the deaths of around 500 Acoma men and 300 women and children after a three-day battle. Of the Acoma who survived the attack, many were sentenced to 20-year terms of bondage. A desire for simpler times - a longing for a world that doesn’t hungrily lap up troubled history from its dish nasty with narrative - is understandable. But times were never simple. The history of this time, ours, will one day add its own flecks of filth to the dish which sullied our ancestors and the generations before us who supped from it yet refused to be its supplicants. So must we. We must still find ways to celebrate life - to desire such celebration, exaltation - as we traverse the traumas of our collective and personal pasts as well as this present-day one manifested itself as a body, one bloated with bigotries, trussed up, oddly tressed, laughable yet unfunny, a made-up male spouting lie after lie from the moue of its mouth.

(Above: Haley Atwell and Tom Hiddleston photographed by Marc Brenner in a rehearsal for their roles as Beatrice and Benedick in Jamie Lloyd’s production of Much Ado About Nothing. Below: Paul Mescal and Patsy Ferran as Stanley and Blanche also photographed by Brenner in Rebecca Frecknall’s production of A Streetcar Named Desire.)

There is always the ballast of art and artists - Tennessee Williams, Shakespeare, Mickalene Thomas - which tries to offer a sense of balance when the battle against the evil dished out to disturb and disorder us, to keep us in disarray and despair, can be enjoined not by justifying it as the enemy but weakening it by infusing the world around it with the empathy it lacks and the joy that injures it in ways it can’t even comprehend in its miserableness measured out in increments of deliberate cruelty. The longing that Williams writes about in Streetcar along with that one unforgivable thing - deliberate cruelty - is his own desire expressed through Blanche when she is talking to her sister Stella about Stanley: “ … Night falls and the other apes gather. There in the front of the cave, all grunting like him, and swilling and gnawing and hulking. His poker night - you call it - this party of apes. Somebody growls - some creature snatches at something - the fight is on .. Maybe we are a long way from being made in God's image, but Stella - my sister - there has been some progress since then. Such things as art - as poetry and music - such kinds of new light have come into the world since then. In some kinds of people some tender feelings have had some little beginning. That we have got to make grow. And cling to, and hold as our flag. In this dark march towards whatever it is we're approaching . . . Don't - don't hang back with the brutes.”

Paul Mescal as Stanley and Anjana Vasan as Stella and Dwane Walcott as Mitch are giving stunningly realized performances in the production of Streetcar which sold out its runs at the Almeida and on the West End and is now back and in the midst of its three-week warmup at the Noel Coward Theatre on its way to New York and the Brooklyn Academy of Music where it opens on February 28th and is scheduled to run until April 6th. But it is Patsy Ferran as Blanche who is revelatory. I saw the production for the fifth time on Thursday afternoon and it remains one of the most stirring and moving - hell, one of the greatest - theatre experiences of my life. And Ferran is giving a performance that will become legendary. I will do my part to make it so. Her interpretation of Blanche - and her talent - astound me. I wrote about it all in an earlier SES/SUMS IT UP column here.

Director Jamie Lloyd is about to have another huge hit with his production of Much Ado About Nothing at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane which officially opens on February 19th and is scheduled to run until April 5th. I saw an early preview on Tuesday night and was won over by it exuberance and glee at its own naughty bits. Tom Hiddleston, who portrays Benedick, is an accomplished stage actor, not just a sexy bloke whom films and television have found ways to exploit. He is so at home in his own body which is gorgeously male and sculpted in whiteness and yet the way he moves and, yes, dances - because there is a lot of dancing that breaks out in this production and singing and music and well-timed rhythmic mayhem - makes us think that all that male white masculinity of his is trying to free itself as well from our preconceptions of it. He’s a delight in this role and it is always a pleasure, a deep one, to witness his stage presence. Haley Atwell is his Beatrice and is well-matched to meet his parrying, rapier wit and sex appeal. They are even moving at times when their repartee falls away and we are allowed to see their true feelings, their longing, their desire. I was moved also to be in the midst of so much joy - a celebration of life - by the end of the production. The audience erupted in it. It was an exaltation. Book your tickets.

During my past months-long visits here in London I interviewed Asa Butterfield and Gillian Anderson for a previous site of mine. Asa played Gillian’s son in Sex Education, a series about, yep, desire and longing. On Wednesday night I headed out to Hammersmith to see Asa in Second Best at Riverside Studios. Beautifully directed by Michael Longhurst, it is a play by Barney Norris written for one character in a single monologue that is wryly amusing and finally deeply touching. It is about a boy who came in second to Daniel Radcliffe to play the role of Harry Potter and how haunted he is by that and other deeper traumas and losses in his life and how they are solved by finding a beginning to a new story for himself and not by just in his dwelling in the past that ebbs and flows about him. It is a play not only about healing, but how hard it is to be the person who is healing after we get so used to being the person who needs it. It is a play about fame and anonymity as well and how we all just want to be seen - finally more clearly by ourselves. As I was watching the play, I remembered how I had told Asa in our conversation that I thought he’d be great onstage but he professed to being frightened to take it on at the time. He did tell me that I was sounding like Gillian, who is a great stage actress herself, who kept telling him the same thing. After he received his well-earned standing ovation, I turned to exit down my aisle and there right in front of me was Gillian who had been at the show that night, too. I recalled all this for her. We shared a few lovely moments and then she continued to head backstage to see Asa where, she told me, she was going to tell him about running into me and this remembrance. The show itself is about finding the quiet moments to celebrate life after the louder traumatic ones keep echoing throughout one’s life. It is about longing to be less lonely within the echoing. Seeing the show itself and running into Gillian and remembering my afternoon with Asa was one of those quiet celebrations for me on what had been until then a rather lonely Wednesday evening.

Matthew Ball and Yasmine Naghdi are about to revive their roles as Romeo and Juliet for the Royal Ballet’s production opening next month. The photo above by Andrej Uspenski is from 2015 when they were rehearsing for the roles. Witnessing their partnership upon the stage at the Royal Opera House over my years here has become one of the great pleasures of my life in London. I spend more time at the Royal Opera House, in fact, than any other theatre. I was bowled over by the Royal Opera’s recent production of Aida directed by the brilliant Robert Carsen which ended its run this week. Indeed, in another quiet moment of synchronicity and celebration like that moment with Gillian out in Hammersmith the other night, I was telling a friend from Paris about how much I loved that production of Aida while we were strolling together through the Mickalene Thomas show at the Hayward when she told me that Carsen was a dear friend of hers. I had no idea. She then stopped to text him my praise of his production and he texted back saying we should all hang out in Paris whenever we are all there at the same time. I had to shake my head, yes, quietly as I felt at the same time the quintessence of gratitude for the everything-connects aspect of friendship and art and artists, and my simple pilgrim’s life infused so grandly by all three. It is in such moments I can almost feel my EVERYTHING CONNECTS tattoo buzzing beneath my latest turtleneck sweater there where it has been embedded on the shoulder I broke back in Paris almost two years ago now and which continues to teach me how in its brokenness and moreover in mine to heal in new ways and how to shoulder that healing. Healing sometimes is the easy part; it’s being healed that can so bewilder me. Shouldering it - as Second Best and Asa’s performance attested the other night - shouldn’t be so hard to do, but it is. And, for me, that’s where art comes in.

Especially ballet.

A Chorus Line’s lyricist Edward Kleban was wrong about his assertion that “everything is beautiful at the ballet” because ballet is everything, even the ugliness and tragedies in life, especially in the story ballets of Kenneth MacMillan which I have grown to love so much as part of my devotion to the Royal Ballet after dismissing for so many years the story form for the purely dance abstractions of George Balanchine whose work, when I was introduced to it back in the 1970s at New York City Ballet, was what transformed my life with its transcendence. The art form, abstract or narratively driven, combines so much - athleticism, beauty, the not beautiful, music, discipline, grace - that appeal to me but so often confound me in other areas of my life. And I have come to realize that because I am at my essence a writer consumed by the wonder of words, it is ballet’s lack of language where I long to dwell for a few desired hours. There is such respite there. Sonnets and the most romantic of poets aside, even I, a requited lover of language, know that language is finally inadequate to explain why one loves something or someone so much. One must just surrender silently and love it. I do at the ballet. I surrender to the silence at the heart of it there within its music and sinew and breath. In fact, after seeing Streetcar on Thursday afternoon, I signed onto the Royal Opera House’s website to see if there might be a cheap ticket to see Onegin for a fourth time that night. I’d already seen Ball and Naghdi twice in the lead roles and Marianela Nuñez and Reece Clarke once. Nuñez and Clarke were appearing again in the ballet later that night and there was a single £14 standing room ticket in the stalls that I scooped up before it could disappear. After three hours sitting in the Noel Coward Theatre, I was willing to stand for three more in the Royal Opera House. Pushkin, who wrote the novel Eugene Onegin, on which the John Cranko ballet, set to the music of Tchaikovsky, is based, wrote in the novel, “Thus heaven's gift to us is this: That habit takes the place of bliss.” My ballet habit is just that for me: blissful. I feel blessed that I am able budgetarily to sustain it.

The other night at Aida, I was sitting up in the far reaches of the left side of the amphitheater when two women in front of me kept talking during the first act and one of them even began to video the performance on her phone. My seat mate -Vanda above - scolded them more than once and then her own seat mate, an elderly Irish bloke who’d been coming to the Royal Opera since he was 15 and first saw Richard Strauss’s Salome, reported them to the house management who reprimanded them during the interval. When they returned to their seats there were heated words exchanged between the women and my seat mates. One of the women snottily claimed, “I can do anything I want.” I finally spoke up. “You can on the street,” I told her. “But not in the Royal Opera House.” That seemed finally to quiet them down and they behaved for the remainder of the evening.

Maybe that is why I love the place so much. I have to behave there myself because when I’m out on the street I tend to do what I want also - sometimes to my detriment. The discipline of the dancers imbues my life with a sense of it if not the thing itself. That in some way is also a definition of the role of art in our lives, it imbues our senses with an added sense it bristles into being. It is an alert: you lowly humans are capable of this kind of exaltation - you are - not just more lowness. Hope reaches out its clever hand because with art it takes on its human form.

When I was writing about Mickalene Thomas as I began this latest column hailing her and her own art and mentioning the decades in which we live our lives, the term “the furniture of home” stopped me when I typed it, as did the doubling down on writing about decades. And then I realized where I had first heard the term and where the word “decade” carried such weight. They are from W.H. Auden’s poem, “September 1, 1939,” which he wrote about an earlier rise of fascism and the lowness of humans, of decades - and the cleverness of hope. It begins:

“I sit in one of the dives

On Fifty-second Street

Uncertain and afraid

As the clever hopes expire

Of a low dishonest decade:

Waves of anger and fear

Circulate over the bright

And darkened lands of the earth,

Obsessing our private lives;

The unmentionable odour of death

Offends the September night. “

…

Down a few stanzas he continues:

“Faces along the bar

Cling to their average day:

The lights must never go out,

The music must always play,

All the conventions conspire

To make this fort assume

The furniture of home;

Lest we should see where we are,

Lost in a haunted wood,

Children afraid of the night

Who have never been happy or good.”

…

The impulse to be good - which is different than goodness - is in some way tattooed onto the shouldering it takes to create art in a world that has never been quite happy to welcome it. It has always held it suspect, like happiness itself. The cleverness of art’s hope is in its continuing to outsmart it.

In this dark march towards whatever it is we're approaching, I will cling not only to the art about me in such a world but everything about me individually - even that which is not beautiful, which is lost, which is haunted - that makes me an artist myself even if I am a second-best one for it is hard for me to claim being an artist at all. It is as hard for me as feeling healed, being healed, staying so.

Mickalene Thomas titled her retrospective at the Hayward “All About Love.”

The most famous line from Auden’s poem about the rise of fascism in another low dishonest decade is this: “We must love one another or die.”

I’ll leave my love right now at art’s door as I head out to knock about in this world where we now live. But I will nurture the tender feelings that are somehow still able to have some little beginnings in me. I will make them grow. I will cling to them. I will hold them as my flag.

I will recognize.

I will rebel.

I will resist.

I will bristle.

I will show an affirming flame.

Onward.

Your words give me hope, which is in short supply these days. Thank you.

I’ve booked about of tickets for shows recently and wavered over Much Ado mostly because they are so expensive £280 in stalls . I know I could get lesser seats but and I know it sounds a bit heathen like I just couldn’t bring myself to hit the buy button . Maybe now I’ll reconsider .