LETTER FROM PARIS: 5/9/25

DAVID HOCKNEY, BEAUFORD DELANEY, REMEMBERING MY MAMA & DADDY , and SLEEPING WITH A BLACK GUY NAMED NERO

1.

I popped up to Paris from Porto for a couple of days this week. Arrived on the 6th. Headed back to Porto on the 8th. I write this now at my desk here this morning as I try to settle not only back into Porto but also into my thoughts about the whirlwind of culture and emotion and sense of home in my homelessness, the haughtiness of it, that I now carry with me throughout the world. The main two reasons I travelled to Paris - I took Transavia, the budget airline owned by AirFrance and had a good experience overall - was to see the David Hockney 25 exhibit at the Fondation Louis Vuitton and the Paris Noir show at the Centre Pompidou, the latter featuring an astonishing array of works by Beauford Delaney, an artist whom I admire and whose alternating mentorship with James Baldwin has always fascinated me and which has resulted for me into the melding of those two men against the menace of their own haughty sense of homelessness where their homosexuality harbored itself. The flow of regard between them could have passed for flirtation but was more about each seeing in the other, these two African American men in mid-20th Century Paris, a respect for their own artistry that on some level was raising to a higher one a refusal to be the flotsam of lives wrecked on the shoals of shame, of America, of race, the rocky thud of otherness where the hull of self had been stuck transformed into the still echoing thunder of these two Black men, a writer, a painter, not partners but partnered, still in some sense parading queerly around the streets of Paris having taken all that was perhaps in such lives and making it the parade of self itself. There is a different kind of loneliness one attains when one ostracizes oneself from being ostracized. They found it in Paris when they were expats there and more deeply discovered it by seeing it in each other. They folded themselves into their own fold. They could be lonely together.

David Hockney was one of my first mentors in New York after I arrived there in 1975 to attend the Juilliard School’s Drama Division. I met him around 1977 or 1978 through my other mentor at the time, Henry Geldzahler, who was then the Commissioner of Cultural Affairs for the City of New York after having been the head of Twentieth Century Art at the Metropolitan Museum. I flew to London, in fact, for the first time, in 1978 with Henry and David on the old Freddie Laker airline, which they thought would be a lark but was not the basically good experience that I just had with Transavia. I even went to Glyndebourne with David to see the production of The Magic Flute for which he’d designed the sets. Henry died in 1994 and there was a memorial service for him at the Met. David spoke at it and afterward we found ourselves together walking down the sidewalk on Fifth Avenue. I told David that Henry was the one who cut me out of the herd and included me in his own fold, folded me into it. Henry let me know that all that made me feel less-than and filled with shame and ostracized were, in fact, the things that made me special in the world where I longed to reside, one where artists paraded about because they weren’t considered perverse or where perceived perversity wasn’t something to be so peeved about. David teared up. “He did the same for me, Kevin,” he said. “He cut me out of the herd, too. Weren’t we lucky to be in Henry’s fold? He saw us. I’ve spent my whole life seeing. It felt good to be seen.”

I think David and I were talking about love that day. I bet Beauford and Jimmy talked a lot about it too when they were walking those Paris sidewalks. I think I have been writing about it in these last two paragraphs. It took me some long sentences to arrive at it but I think that’s what I’ve been getting at.

I got there in Paris itself when I was walking alone on its sidewalks this week and realized that May 6th and May 7th are the birthdays of my parents, Howard Jean and Nancy Carolyn. My mother was born on May 6, 1931. My father on May 7, 1931. They lived in a tiny town in Mississippi called Harperville and were in the same classes growing up. They were childhood sweethearts who married. In 1963 my father was killed in an automobile accident. In 1964 my mother died of esophageal cancer although I have always thought it was a broken heart more than the cancer that did her in. The fold of family became my little brother and little sister and our maternal grandparents, Mom and Pop, who raised us out in the Mississippi countryside. I was 8 when we moved in with them. My brother was 6. My sister was 4. We are all in our 60s now. That’s Mama and Daddy down below in their senior portraits from Harperville High. I wondered in Paris during their birthdays what they would make of me wandering the world now in my haughty sense of homelessness that began not when I left home at 19 but when they left me and my little brother and sister even though Mom and Pop loved me unconditionally, so much so that they let me go when I was still so young and where out here in this world where artists parade about I’ve been wandering in a state of sad wonder ever since.

There was a lot of joy in the wondrous David Hockney 25 and Paris Noir shows but they were limned with the heightened sense of sadness that wonder can leave in its wake, that art can. All that perhaps parading about as art can’t finally frame the reality of the world, the shoals where shame and pride swirl about in our preening lives that demand that art try to capture what we trust it cannot for art might be elitist but we finally feel superior to it in our hubris. I often say that I have spent a career living just outside the frame of fame. It was a good place for me to set up a career as a writer because like all artists - and I have lived through a long sentence of long sentencing to get to this point of thinking of myself as an artist - I live too just outside the frame of self. The sight lines are just better here from which to see it all - hubris and its human hues - through such a prism.

“I believe that the very process of looking can make a thing beautiful,” Hockney has said. “It takes a long time to make it simple. If you see the world as beautiful, thrilling and mysterious, as I think I do, then you feel quite alive … I think I’m greedy, but I’m not greedy for money – I think that can be a burden – I’m greedy for an exciting life. I want it to be exciting all the time, and I get it, actually. On the other hand, I can find excitement, I admit, in raindrops falling on a puddle and a lot of people wouldn’t. I intend to have it exciting until the day I fall over.”

Baldwin: “Beauford was the first walking, living proof, for me, that a Black man could be an artist. In a warmer time, a less blasphemous place, he would have been recognized as my Master and I as his Pupil. He became, for me, an example of courage and integrity, humility and passion. An absolute integrity: I saw him shaken many times and I lived to see him broken but I never saw him bow … I remember standing on a street corner with him waiting for the light to change, and he pointed down and said, ‘Look.’ I looked and all I saw was water. And he said, ‘Look again,’ which I did, and I saw oil on the water and the city reflected in the puddle. It was a great revelation to me. I can’t explain it. He taught me how to see, and how to trust what I saw. Painters have often taught writers how to see. And once you’ve had that experience, you see differently … The reality of his seeing caused me to begin to see.”

The realty of my parent’s deaths did the same for me, no longer seeing them caused everything else to be seen in the ironic relief of their absence. That is where the sadnesses of my wonder and my wander began. Art helps. It just does. I fold it into me. The rest is just fumbling about.

2.

I am always moved by children being brought to cultural events by parents as I am by the elderly still insisting that they be brought there as well. I took these two photos above during my time at the Hockney exhibit between texting my brother, who is an OB/GYN and a sculptor and artist. I often text him as I am perusing art exhibits to show him some of the art and discuss it as a way to delve into our lives. During the Hockney stroll the other day, he mused on our each having such an appreciation of art and being artists ourselves and each of us having “an eye.” He wondered where that came from since we were not taken to such cultural events as children and inculcated with it. We actually lived childhoods of deprivation where art was concerned. I often wonder myself if it is indeed that lack of it that made us long for it, the lack that indeed gave us “an eye” to make up for it.

We never got to know our parents really - I have many more memories of them than my brother and sister who barely recall their presence in our lives - but I do think we might have inherited some of our affinity for art and culture from them. I have two vivid memories of my father. One is his sitting with me and drawing landscapes. He even acknowledged my love already of words and letters and told me the way to draw a bird in flight was to think of it as an “M” and then flatten it out so it looked like a pair of wings. The other memory is sitting and looking at shelter magazines curled up next to him and his discussing the beauty of the rooms as if we were strolling through art exhibits together. I felt his own longing for beauty in his life. I feel it still in the longing for it in mine. My mother, in fact, had an eye for interior design and certainly fashion. She was stylish. Loved a popped collar. I texted my brother from the Fondation Louis Vuitton the other day that I have come to trust the aesthetic judgements of women who love a popped collar and distrust those of the men who do.

At the Hockney exhibit, I was even more moved by children and the elderly being there because the show’s focus on the last 25 years of David’s work reveals how he has become at 86 more childlike in his thrilling application of the beauty and the mystery of the world about him. There is an abundance alas of landscapes and I am not a big fan of landscape paintings. Sorry, Daddy. Sorry, David. Turner can turn me on to them when I am in the presence of his landscapes because he seems to be seeing through them into their mystery and not celebrating the simple thrill of being one with nature but instead distinct from it. I like David’s early work more than his later - and his portraits and drawings more than his landscapes. I even saved the beginning of the show for my own ending of it circling down to the basement galleries at the Fondation to take it all in as a finale - but there were even more landscapes down there, gigantic and glorious ones. For all the simplicity in his own “eye” there was a lot of grandeur to that landscape aspect of the show. Of all the landscapes, I liked this simple apple tree below the best.

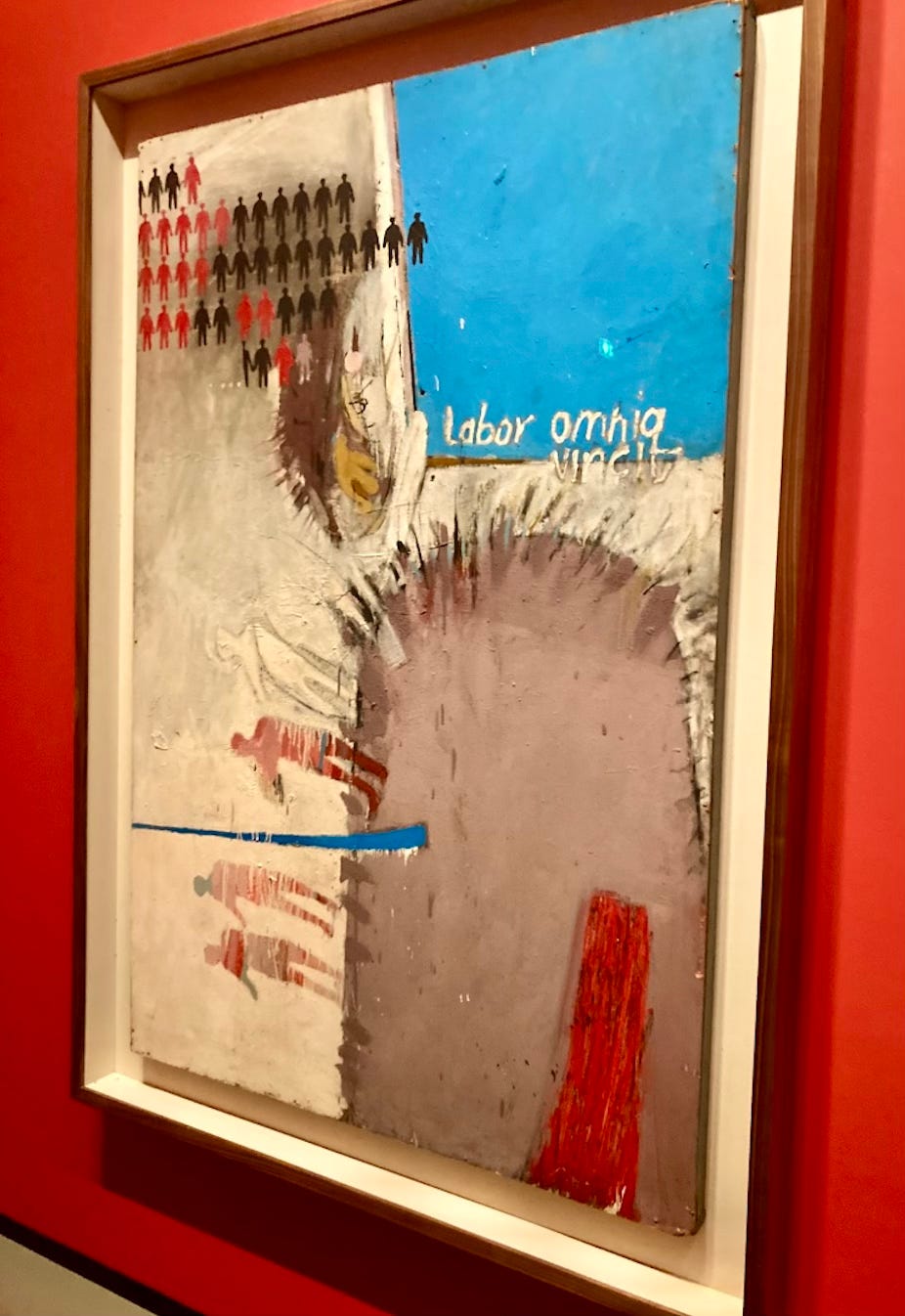

The early painting below from 1960, Labor Omnia Vincit, is the third in the exhibit down in the first of the basement galleries. It is encountered after a portrait of his father and a piece called Bolton Junction, both done in 1956, the year of my birth. The 1960 work is a kind of mission statement for the rest of his career. The title is the motto for his hometown of Bradford, England. It means “Work conquers all.” After spending more than two hours roaming slowly around the show I was reminded of what Bette Midler once told me about Picasso and visiting the museum named for him in another part of Paris. “When I went to the Musee Picasso in Paris … well, I find it's an odd place. On one hand it's full of Picassos,” she said, “and on the other hand it's kind of a mess. It's haphazard. I'll never forget it. You would think that his shrine would be totally pristine, because he was one of the greats. He was legendary. But the one thing I took away from my visit to that museum was that this guy jumped out of bed in the morning and had to make things. He was obliged to; he was compelled to. In a way, I have a little bit of that, though not to the degree that he had it. But I feel I have to create. I have to dig in the earth, I have to make something grow, I have to bake something, I have to write something, I have to sing something, I have to put something out. It's not a need to prove anything. It's just my way of life."

Art is David’s. The making of it.

3.

I only have so much space in each column. I could write a whole one about the personal narrative I told myself that conflated with so many of the paintings and works in the show that run parallel to my life. But it also feels like showing off a bit even more than I already have about that conflation. I’ll save that for texts with my brother when I send him so many of the other photos I took at the show. And of the Paris Noir one.

I was moved to tears though in three rooms toward the end of the Hockney exhibit. When I happened upon this portrait below of Henry and his boyfriend, Raymond, from 1979, which I’d never seen before, my eyes suddenly filled with emotion. So many memories came flooding up the moment I walked into this room and saw this. “Oh, Henry,” I whispered. “Raymond.”

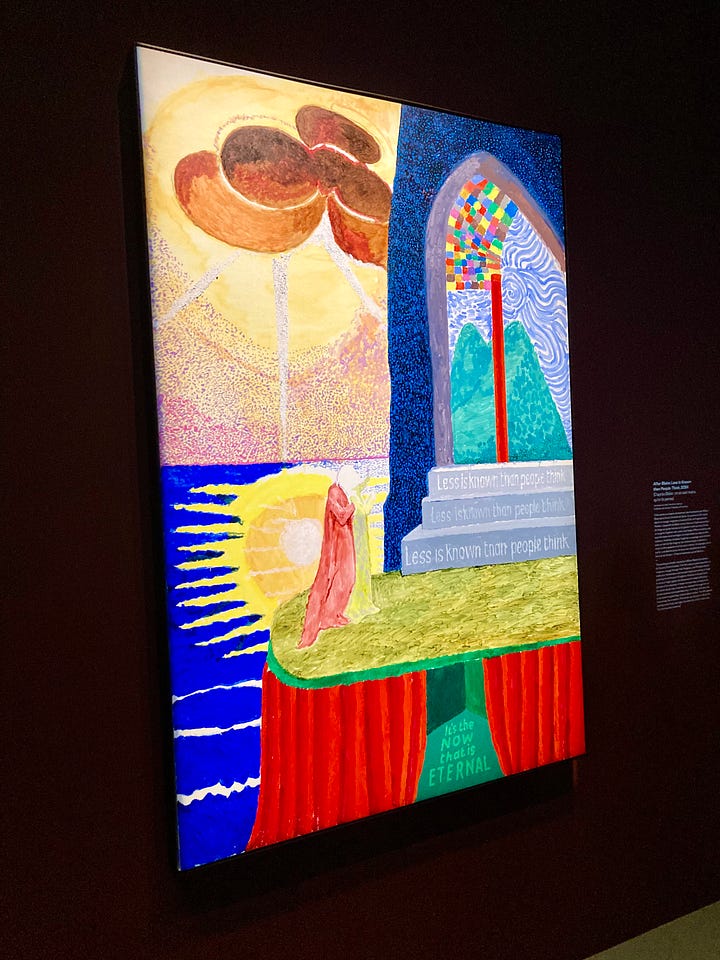

Already emotional, I was even more moved by the little chapel-like room next door with a few of his latest works which David himself describes as having “a more spiritual” dimension. The room is labeled LESS IS KNOWN THAN PEOPLE THINK. The first below is After Munch: Less Is Known than People Think. The second: After Blake: Less Is Known than People Think. And finally there is the self-portrait which references one of his early works from the 1960s: Play within a Play within a Play and Me with a Cigarette. It is a portrait of him conjuring this portrait. I zoomed in on him in the second photo so you can read his button: END BOSSINESS SOON.

After these rooms, I walked into the massive immersive one in which his stage designs for opera are projected and animated to the glorious sound of the operas. I was overcome at that moment by memories of his driving me through the hills of Hollywood in its magnificent ever-changing late-day light to the strains of Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde as the same strains came blaring forth at me when I walked into the room to the sight of his sets. “‘Do I hear the light?’ Tristan sings here,” David said over the music as he drove us around a curve toward even more light. “Do you hear it?” I’ve heard it ever since.

4.

This is the Black guy named Nero I slept with during my Paris visit. He was one of the two cats - his brother is named Felix - who live in the Airbnb where I stayed with my lovely host named, yep, Kat. She also has a dog named Milo but he’s a mama’s boy. Nero and Felix sort of tag-teamed me during each of the two nights I spent there but Nero was the one who’d spoon. I loved this more than you can know. It made me miss Matty and Finn, the two cats I had to re-home to live my pilgrim’s life which included during this trip my seeing The Seagull at the Comedie Francaise and Titanique at the Lido but the strict limit to my column space doesn’t allow me to write about them. I’ll try to do so next week in my RECIPES & REVIEWS.

5.

I heard the slow rumble of Baldwin’s thunder behind me at the Paris Noir exhibit on the same day a new pope was named. I turned around and saw this video.

Everything connects.

What an odd coincidence. My mother was also born on 6 May, 1931. In a different country on a different continent, but on the same day.

Those long rambling sentences where you tease out meaning are like archeological digs. Thank you.