LETTER FROM PRAGUE: 12/20/24

24 YEARS AGO I WAS HERE WITH HEATH LEDGER AND BRUCE WEBER WRITING A COVER STORY FOR "VANITY FAIR," YESTERDAY I WAS IN A DENTIST CHAIR GETTING A ROOT CANAL. TODAY: I CONNECT THE TWO

(Above: Heath Ledger photographed by Bruce Weber in Prague for a Vanity Fair cover story I was writing here where Heath was making the film, A Knight’s Tale. The photo above is now on display at the Prague City Gallery in a career retrospective of Bruce’s work titled My Education. Below, Heath and I during that week I hung out with him in Prague. Looking now at the photo of us and knowing what was to come, I am haunted by the shadow of the image hovering there over him.)

1.

What a difference 24 years make, I thought, as I sat in the Bolt car with the young Czech driver listening to a radio station playing songs sung in rap-like Czech mixed in with older American tunes I sort of recognized since the rhythmic recognition of them was a bit off as the sounds of the Czech language searching high and low for a vowel here and there in their interpretive renditions of old rock-n-roll anthems was punctuated by post-punky dusted-off New Wave ditties and something that sounded like the blues blurred into whatever pain causes people to sing them in Slavic tongues, a mishmash of misshapen music that serenaded me in my own pain which was searching itself for relief there somewhere on the outskirts of Prague. The last time I was here at the turn of the century I was heading to the city’s Barrandov Studios which was built by the family of Vaclav Havel in the 1930s in order for me to continue to work on a cover story about Heath Ledger who was filming A Knight’s Tale there on one of its backlots. Yesterday I was heading toward a dentist’s office to get a root canal. I can feel achingly alone and lonely at times on this pilgrimage that is now my life led in the ever widening world that can at times seem instead very small when that loneliness corners me as it did yesterday in that cramped front seat in an airless little car called a Skoda Octavia which is manufactured here in the Czech Republic. I hummed along with that blur of blues as I tried to bring into focus the memories I have of this place, among them Heath and his own blurry smile when we smoked pot together late one night walking along the Charles Bridge after a party we’d attended with other members of his film’s cast and crew. Recalling that as I was experiencing the car ride and trying not to get motion sickness along with the tooth pain, I suddenly remembered something that poet Howard Moss, who was the Poetry Editor at The New Yorker from 1948 until his death in 1987, had once written to me at the end of a long letter he had sent to me in the early 1980s in which he told me, after reading one of the short stories I was composing at the time, that I was indeed a writer - he likened me as well to a Commissar of Culture - yet pointed out that what I was missing so far in my then young already-rather-connected life was alchemy. And then from the Skoda’s staticky radio came the English lyrics of the German synthpop band Alphaville …. “forever young/I want to be forever young/Do you really want to live forever?/Forever, and ever/Forever young …” in a version sung by a Czech artist who switched back to Czech to sing all that was not that refrain. Ledger, forever alas young, had suffered an overdose at the age of 28. I am now 40 years older than that having survived my own drug addiction. “ … oh, Heath …” I softly whispered. “Huh?” the driver asked, the only sound he uttered the whole half hour it took to drive me to the complex where the dental office was located. I pretended I didn’t hear him. “ … forever young …” the Czech artist sang. I lowered my window. I longed for a bit of air. I longed for my pain to stop. I longed for alchemy. I wanted to cry. I didn’t.

2.

3.

Setting out from House at the Big Boot, the lovely little family-owned inn where I was staying on the first of my week-long visit here in Prague as a respite from Vienna (I highly recommend this inn, right across from the German Embassy), I walked over the Charles Bridge toward the Prague City Gallery to see Bruce Weber’s retrospective. I shook my head at the highly coincidental nature of my life - if not its alchemical one - when I heard that he had this show of his work here since that only other time I had been to Prague was to share the Heath assignment for Vanity Fair with his crew and him. The show is keenly curated, even mindful. Yes, it is homoerotic. Yes, its focus on celebrity is quite sly without ever resorting - or rising? - to being its sleuth. There are fashion shoots which contextualize the clothes as being narratively conversant with the bodies they cover and not speaking some other story-less language. It all has the swing and sway of the 1980s and 1990s, the decades that gave us the swag bag of sexual swagger, unapologetic in its tendency to bump into what was in its busily booked obstacle course of coarseness reconfigured as sexual cunning, a coquettishness re-cocked to test what was tasteful as testosterone strategically roamed the frame with as much objectified abandon as the estrogen stratum, that is until it was the thing itself, that swinging swag bag of swagger knocking about, that got knocked off-course and became not just the wrong kind of accessory but the purse that the pursed-lipped posses trashed, dispossessed. The times changed. The objectified objected. Agency became something models correctly insisted on having in their own lives and not just the name of the kind of company that handled them. “This show is rightly a resurrection since Bruce has been in a kind of cultural wilderness for a while,” I told its producer, Milosh Harajda, when I ran into him as I wandered its rooms in the Stone Bell House and alluded to some of the Me-Too fallout that fell Bruce’s way. That got only a wan smile from the talented curator so I moved on to talk more about Heath and that time Bruce and I shared here in Prague since Bruce Weber is not, as this show attests, a cancelled Czech. That pun is labored perhaps but the work is not. It has aged well - like Bruce himself. I am not sure if it’s art, but it is artful in its nonchalance. And because of the wilderness from which it and its creator have emerged there is an ache to its archness that is quite moving. It’s complicated even if the work finally isn’t and that too is the tension of observing all the beauty and the bodies that Bruce has for decades now with an aesthete’s hungry eye discerned and sorted and sent forth our way.

Of all the images in the show, however, I was most struck by the small nude portrait of a young man whose anomalous mostly limbless body had been congenital. It reminded me of the nudes and portraits of amputees taken by the New Orleans photographer George Dureau. The nude young man was caressing his pet snake with his two arms that only reached to what one could imagine to be elbows if he had had them. The man was someone Bruce had met at a leather bar in the East Village back in 1972 when he was on an assignment from his photography class taught at the New School by Lisette Model, the Austrian-born photographer who is known for the frankness of her framing of the human condition, its form if not its beauty. Bruce was introduced to Model by Diane Arbus. “Lisette gave me the courage to stand my ground and push my pictures in unexpected directions,” he claims in a quote next to the nude. “She taught me that I could choose a unique path, and that I didn’t have to give into anybody else’s ideas of what photography should be. My entire artistic life has felt like an extension of Lisette’s class and the lessons I learned there.”

I also liked the faceless portrait of CZ Guest that has been chosen for the exhibit. There is an architectural quality to it that does not rely on any form of beauty, just form itself. It, like the young man from 1972 with congenital anomalies, stood out in the flow - image after image after image - of breezily idealized eroticism.

I was most moved by the last room that becomes a kind of temple of sorrow and grief for Stella Tennant who, like Heath, died unexpectedly, tragically, still much too young. There are banners of her beauty. Her presence. There is a stoicism to how she has been so grandly stored away here at the end of the show for you to come upon her and upon that grief, the silent acknowledgement that can accompany it for all your life after its having come upon you.

Photography: the silent acknowledgment, the stoicism of the steadily held lens. There is no stealth to Bruce Weber’s work as there is to the work of other photographers - Beard, Weegee, Kertesz, Lartigue, and, yes, Model. But neither is it staged in the sense of Leibovitz. It is instead deeply attuned to attitude, a stand against the stance.

(Above: Teenage Beauty by Lisette Model. Provincetown, Massachusetts. 1944)

(Above: CZ Guest by Bruce Weber. Palm Beach, Florida. 1988.)

4.

There was nothing silent about the ending to my Heath Ledger story in Vanity Fair. So back to music here in Prague. I wrote in its final two sections:

Rock Eisteddfod?

“It’s a nationwide high-school competition,” says Ledger. “It’s a dance thing. You get about 60 or 80 students. You have to create an eight-minute dance piece to a topic you’ve picked. You have to create your own sets and costumes. And you’ve got a month or two to do it. Usually a lot of girls’ schools do it. We were the first all-guys school to ever do it. Our topic was fashion” he says with an actory aplomb that could send his leading lady reeling. “It was pretty cheesy. But we won the competition. I choreographed the whole thing. Sixty male students—all farmers at a military school— who had never danced before. We were doing it just to get out of school and go to the competition so we could meet all those girls. We went through all the different aspects of fashion. It was cool, man. These kids had never danced and didn’t think they could do it. I remember the first meeting we had. All of them were kind of surly, going, ‘Fuck this. I’m not gonna dance.’ I had to literally get up in front of all these surly guys and put on a song and just dance. By the end, when they won the competition, they were so fucking blown away by it. For starters, that they could simply win something, but also that they could dance. I guess it was like a Gene Kelly movie. Like Summer Stock.”

You might think that Ledger’s cinematic hero would be Steve McQueen or Paul Newman or Marlon Brando or James Dean. “No, it all comes from my love of Kelly. I think he’s just awesome. It was more or less the partnership between him and Judy Garland that I liked. He nurtured her and had her under his arm,” he says, miming having a phantom Garland in a gentle headlock. He pats her invisible head. “I really loved that. There was something so magical about Gene Kelly’s films. It was moviemaking! They built those amazing sets! They danced and sang!” He pauses, trying to decide whether he should admit something or not. “Actually, I have a pair of tap-dancing shoes,” he says. “I was living on Waverly Place in Greenwich Village for about six months, and one day I went to Capezio’s and bought myself some shoes. I haven’t had a lesson yet. Like everything else, I’m self-taught. I do it by myself in my apartment.” Lighting his last cigarette, he has to laugh at the image of himself privately step-ball-changing in front of his mirror. “God! Doesn’t that sound lonely?” he asks, taking a long slow drag.

Ledger has never bothered with acting lessons, either. “I don’t have a method to my madness.... For me, acting is more about self-exploration. I’ve learned a lot about myself in order to learn about the craft. How many kings can you find to play a king? You can’t find them. When I act, I look at it as if I’m a mixing board in a sound studio. The pattern on the board is me. When I play a character, I go, ‘I’ll turn these knobs down and these ones up.’ But in order to do that I have to know myself. I have to know myself like an instrument. I’m just a saxophone,” he says, shrugging. “I’ve always been very big on self-exploration and answering my own questions. For so many, it’s hell growing up. But I guess I’m blessed. I’ve really enjoyed it. I don’t let a lot get to me. I really don’t. As I keep saying, I break everything down. Everything. I look up at those stars,” he says, pointing at the sky above the Vltava River, “and go, ‘There’s no explanation for us to be here.’ When anything is blocking my head or there’s worry in my life, I just—whoosh—go sit on Mars or something and look back here at Earth. All you can see is this tiny speck. You don’t see the fear. You don’t see the pain. You don’t see the movie industry. You don’t see this interview. You don’t see thought. It’s just one solid speck. Then nothing really matters. It just doesn’t.”

‘Aaaannnd … cut!”

Ledger pulls off his helmet and hands it to a costume assistant. Scowling, he trudges over to the playback monitor to watch the sword fight his character, Sir Ulrich von Lichtenstein, has just won. Richard Greatrex, *A Knight’s Tale’*s director of photography, whose credits include Mrs. Brown and Shakespeare in Love, readies his crew for the fight’s next take. “I met Heath once before. I’d shot his screen test for a Miramax film called Calcio, which is the Italian word for football. It was about an English football fan who ends up in Sardinia. The film got canceled at the last minute because Harvey Weinstein [Miramax’s co-chairman] didn’t like Heath. The director and Harvey had quite a disagreement about him, and the thing fell apart only a week before we were to start shooting. I think Harvey must be kicking himself now, considering all the buzz about the boy.” (Weinstein, through a spokesman, claims that he doesn’t recall such a film.) In fact, Miramax, along with Paramount, is producing Ledger’s next vehicle, The Four Feathers. Ledger, for his part, refuses to answer—but does smile knowingly—when he’s asked if he “stuck it to Weinstein” during the salary negotiations for The Four Feathers, considering the producer’s past failure to appreciate his talent. (Sources say Ledger will cross the $2 million threshold.)

Greatrex continues: “I spoke to director Gillian Armstrong just before I came to Prague, and she was raving about Heath.… He certainly knows his way around a set. He knows where his body lies in the space very well. He understands the 3-D-ness of movie acting. He’s very skilled at that.” A giant shadow falls ominously across the sword-fighting ring. “Oh, God! Look at those dark clouds rolling up.”

Ledger emerges from the tent where the playback monitor is now stationed. He is still scowling. The costume assistant attempts to loosen a bit of the armor on his biceps, for he is getting badly bruised with each two-handed swing of his sword. “I wasn’t graceful enough,” he growls, addressing what he just saw on the monitor. “Any fool can fight. I have to find a way to be more graceful.” He is able to dismiss the hovering assistant by quietly thanking her. Groaning at the weight of his armor, he slips his helmet back on. Once again he lifts his sword, ready for another morning of dolly shots and shouting extras and a close-up or two of his angry eyes, grouted beneath his visor.

By lunch the swordplay is finished. Perspiring heavily, Ledger removes his armor and shirt until he is wearing only his leather leggings. He puts a Janis Joplin CD into his boom box. On a hillside next to his trailer, he attempts to stretch his sore body to Joplin’s singing. (The day before, in a better mood, he stretched to the soothing tones of Tracy Chapman.) Finally sitting down to a plate of meat loaf and potatoes—his curls blowing in the rising wind—he’s asked if Heath is a shortened version of Heathcliff. “No, just Heath. But I do have an older sister named Kathy,” he says. “Well, Kate.”

There is a thunderclap, and a downpour erupts. The cast and crew head for cover. Their star stays put. He slips Joplin from the boom box and slides the Doors in. “Riders on the Storm” begins its own distant rumble. Ledger turns his face to the rain and heads up the hill. The Czech sky is roiling. “Into this house we’re born,” Jim Morrison sings. “Into this world we’re thrown.” The stones have become slippery. Ledger picks up a few and heaves them toward the heavens. Ray Manzarek’s keyboard gets his feet tapping. A rock ‘n’ roll Gene Kelly, he’s found the grace he misplaced this morning and, grinning from ear to ear, stomps about in one puddle after another. Lightning flashes. He ignores it and keeps on dancing.

5.

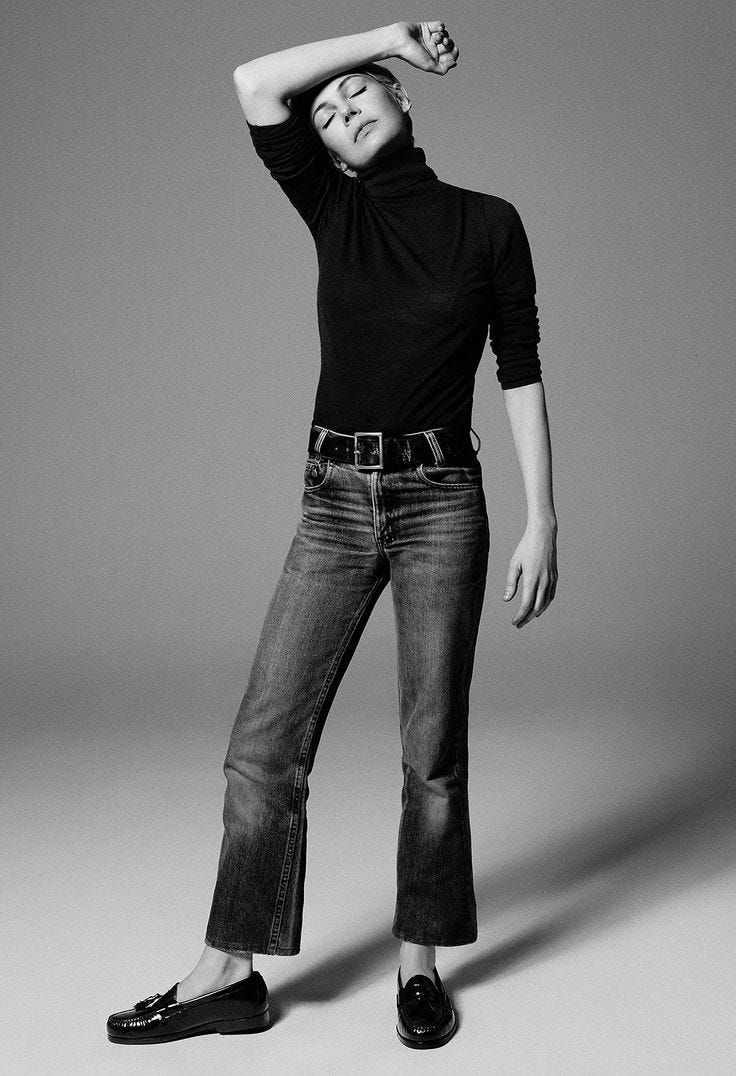

(Above: Michelle Williams photographed by Daniel Jackson in 2017 for WSJ Magazine.)

I was assigned an interview with Michelle Williams for The Daily Beast a few years after Heath’s death. She agreed to meet me in the Brooklyn townhouse she had shared with him and the child they had together. I got to the neighborhood a bit early and browsed a used book store on Smith Street and, knowing from my research that she was a big poetry reader, I bought her a collection of poems by Howard Moss as a gift. When I gave it to her, I also made an amends for having smoked that joint with Heath on the Charles Bridge in Prague. At one point, I had thought it the coolest thing I’d ever done in my life but after his death from an overdose I had been haunted by having done it. She thanked me for the amends then gasped and teared up when she saw the name of the poet on the collection. “I was just trying to remember the title one of his poems this morning,” she said. “It helped me get through my grief after Heath’s death.” She ran her finger down the Table of Contents. “Here is it is,” she said. “‘The Pruned Tree.’” There it was: the silent acknowledgement, and within it, she seemed to have felt Heath’s presence. I know I felt Howard’s. As she quietly read the poem aloud, I also knew there was more than coincidence to my having bought her that book after she had been trying to remember that poem by Howard that very morning; there was alchemy.

THE PRUNED TREE by Howard Moss

As a torn paper might seal up its side,

Or a streak of water stitch itself to silk

And disappear, my wound has been my healing,

And I am made more beautiful by losses.

See the flat water in the distance nodding

Approval, the light that fell in love with statues,

Seeing me alive, turns its motion toward me.

Shorn, I rejoice in what was taken from me.

What can the moonlight do with my new shape

But trace and retrace its miracle of order?

I stand, waiting for the strange reaction

Of insects who knew me in my larger self,

Unkempt, in a naturalness I did not love.

Even the dog’s voice rings with a new echo,

And all the little leaves I shed are singing,

Singing to the moon of shapely newness.

Somewhere what I lost I hope is springing

To life again. The roofs, astonished by me,

Are taking new bearings in the night, the owl

Is crying for a further wisdom, the lilac

Putting forth its strongest scent to find me.

Butterflies, like sails in grooves, are winging

out of the water to wash me, wash me.

Now, I am stirring like a seed in China.

6.

I am having trouble holding this lens steady.

Being stoic.

Artful.

Nonchalant.

7.

… oh, Heath …

So much to say.. instead. Let me add. Do not let this go to your marvelous bald head. You match Ledger in looks and still movement.