LETTER FROM TANGIER: 6/26/25

A PILGRIM POETICALLY READING BECKETT IN THE KASBAH WHILE THINKING OF HIM READING DANTE THE PILGRIM AND THE POET HERE, or BILLIE WHITELAW & BAKING CAKES & THE CONNECTIVE EVERYTHING OF NOTHINGNESS

1.

GNOME

by Samuel Beckett

Spend the years of learning squandering

Courage for the years of wandering

Through the world politely turning

From the loutishness of learning.

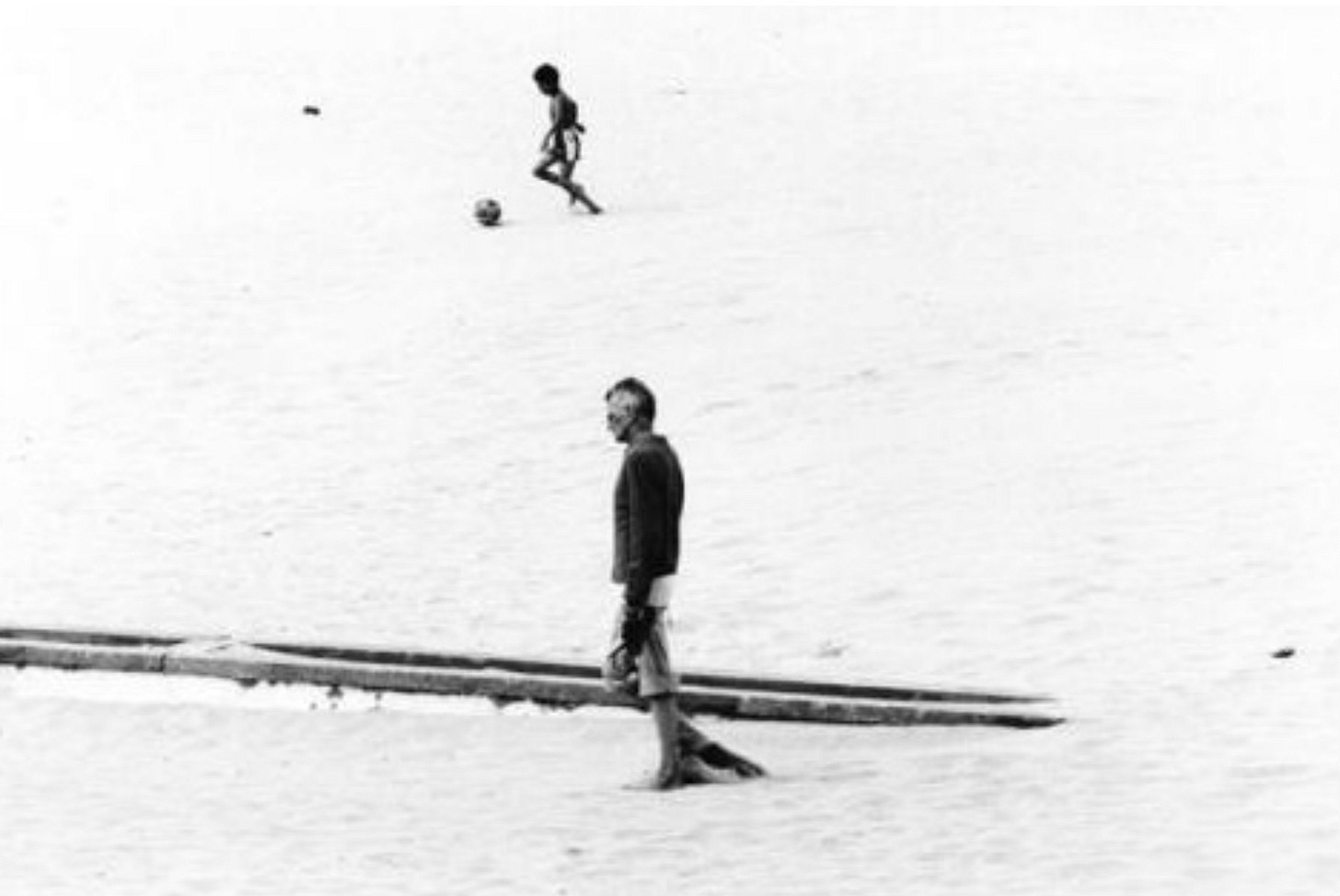

The first photo above of Samuel Beckett - and the two others of him I am posting in this week’s LETTER - were taken by photographer François-Marie Banier when Beckett and his wife, Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil, were visiting Tangier in 1978. The second photo is one I took a couple of days ago when I exited the building where my dentist, Dr. Marya Semlali, has her office on Boulevard Pasteur after we had another bonding session for my teeth but also, I confess, for the two of us as well. I’ve grown quite found of her. If I were straight, I’d have a mad crush on her. And yet because I’m gay perhaps that is exactly the kind of crush I have, a mad one. I looked across the boulevard upon exiting her building at that cafe there that beckoned me in the way that Tangier itself does as it signals its past by always being stubbornly present. When I looked at the two photos later it were as if they had a mad crush on each other, an odd sort of connection I keep trying to figure out although the cafeteria’s neighbor right beside it is the legendary bookshop Librairie des Colonnes which was opened in 1949 and saved in 2010 by Pierre Bergé. Beckett, who found respite in Northern Africa in another of his odd connections he kept trying to figure out, also liked to head to Tunis for some recuperative reading and relaxation when he was feeling low. But Tangier where he’d drop into Librarie des Colonnes seemed to add something singular to his gait, not grace exactly because he was never really looking for that but instead its ballast. Maybe it was just more maybe that moved him about as it signaled past him toward the present to which he, better read than dead, still stubbornly strides.

“About thirty years ago, the beaches and streets of Tangier were haunted by an automaton,” Banier, having noticed that stride, wrote as an introduction in a book of his Beckett photos. “It was nothing but skin and bones, and I often lost sight of it, blinded by the sun. Its silhouette of a marsh-bird vanished in the middle of the crowd of Moroccans in djellabahs and indifferent tourists. Like me they ignored the fact that this skinny man was the great writer Samuel Beckett. His path seemed to follow the movement of a pendulum, adjusted to his own rhythm, his heels touching the ground long before his weight followed, the body leaning backwards. He looked far above the horizon, his ocean blue eyes hidden by big sunglasses, and tried to orientate himself. It troubled me so much not to be able to capture the real dimension of this figure that I often forgot to put film into my camera.”

Banier continued: “As our paths kept crossing we finally met. So I abandoned the camera and stopped taking pictures. With his dark voice, he told me of the twenty seven books he couldn’t find a publisher for, of his wife Suzanne, of his friendship with James Joyce, of his family in Ireland. He imagined how his mother would have been surprised by him getting the Nobel Prize, if ever she had known; he advised me to read ‘to learn how the others do it.’ But I wanted to retain this attitude and his face, so I had to step away, to leave the treasure of his words, his opinions, and get back to the place that suits the photographer best: the one behind the lens.”

Beckett’s place that suited him best was amidst the silence-staining words, not behind them. He also liked to write letters. Liked? Hmm. Let’s say he felt compelled to compose them more than he felt any affection about their composition. Many of his letters from seaside towns - especially Tunis and Tangier - mention his rereading Dante, the writer (passed on to him through Joyce) to whom he returned over and over and within whose works he strode in the stillness that so often steadied him in his teetering (never doddering) brilliance, his own work a kind of third pilgrimage alongside Dante’s doubled one. Beckett had a life-long fascination with number games - they are embedded in his work - and he was intrigued with the numerical symmetry of The Divine Comedy. In his essay about the work, "Dante...Bruno. Vico…Joyce,” he, this writer known for his trilogy of novels - Molloy, Malone Dies, and The Unnamable - along with his 26 plays and a bit of poetry, points out the critical importance of the number three: three books with thirty-three cantos written in three-line rhymes. I can often squint in search of the triunities threaded like tributaries in his streaming texts of consciousness as I try to figure out how he did it, a kind of unlearning of all that I have learned. Beckett’s first short story is titled “Dante and the Lobster.” In Deidre Bair’s biography of him, she claimed that a friend of his, Walter Lowenfels, said to him in 1932, “You sit there saying nothing while the world is going to pieces. What do you want? What do you want to do?” Beckett, wrote Bair, “crossed his legs and drawled: ‘Walter, all I want to do is sit on my arse and fart and think of Dante.’” I like to think of courtly Sam sitting at Le Claridge having a third cup of coffee, farting thrice, and thrilling at the symmetry of it and the ellipses in the midst of which he also sat, and … Dante-finally-like … sighed …

Billie Whitelaw, the British actress who was Beckett's muse for a quarter of a century - that’s Sam directing her above - gave a rather “dental” performance when strapped into a chair in the darkness for the 12-minute play he wrote specifically for her, Not I, only her mouth illuminated as she recited it all at the Royal Court Theatre with a heart-racing briskness, full of breath control and an awe for her own fear, a verbal canter, a caterwaul that couldn’t quite, that can’t, a cantankerous bird beneath her tongue tied to flight, not its. Watch it here along with an introduction by Whitelaw. I highly recommend you do so. “Plenty of writers can write a play about a state of mind,” she says in the intro to the filmed performance. “But he actually put that state of mind on the stage in front of your eyes. And I think a lot of people recognized it. I recognized it. When I first read it, at home, I just burst into tears because I recognized the inner scream. Perhaps that’s not what it is, I don’t know, but for me, that’s what I recognized, an inner scream, in there, and no escaping it.”

You can also listen to her talking about rehearsing with Beckett here for a production of his of play titled Play in 1964 at the National Theatre. She talks about her musical approach to acting his work and its being about “rhythm, pauses, and lack of pauses.” And in an interview with Mel Gussow for The New York Times in 1984 when she was appearing in three short works by him off-Broadway at the Samuel Beckett Theatre directed by Alan Schneider, who also directed the American premiere of Waiting for Godot in 1956 (the year I was born), as he did so many other works by Beckett, Whitelaw said, “The first note Sam ever gave me was years ago when we did Play. The script is filled with one word followed by dot- dot-dot, two words, dot-dot, and he said, 'Billie, would you make these three dots, two dots?' He took a pencil and crossed out a dot. That sounds pretentious, but it makes a difference.''

Although Whitelaw portrayed Desdemona opposite Laurence Olivier’s Othello at the National, she was not a trained actor. Somehow acting did however more deeply help her solve her childhood stutter - as it did mine when I found a way not to speak in my own “voice,” so much so that I was accepted into The Juilliard School’s Drama Division after having auditioned for it just short of my 19th birthday. Indeed, I think I first became a writer as a child even before I decided I wanted to be an actor as a teenager because I didn’t stutter when I wrote within the eloquence my silence offered, an eloquence so stymied by each utterance a stutter studded. I still stutter. I still write. I write these words - these - within a silence which is my own truest North Africa where I find the respite I keep trying to figure out.

I not only have always loved Whitelow because of her association with Beckett and her singular talent to meet the demands of his work, but also because of that: our being stutterers in our childhoods. Our fathers also died when we were both children. I was 7. She was 9. That hardscrabble fatherless childhood bereft as well of money was perhaps one of the reasons for her lack of actor-y airs, another reason for my having always adored her. Maybe that’s what Beckett loved about her, too. What did she offer him? “My center,” she once said. “I gave him the whole of my gut.” To academics Beckett is about the poetics of existentialism; he gives it such propulsion that even his silences seethe with the vibratory impatience of that sound of nothingness, a stutter without the words, always standing by. But to those of us who are not scholarly, Sam is about the viscera of existence, the fatal filtering of instinct though the fraying human fray, which he knew he could translate through the sensible Billie and her centered gut.

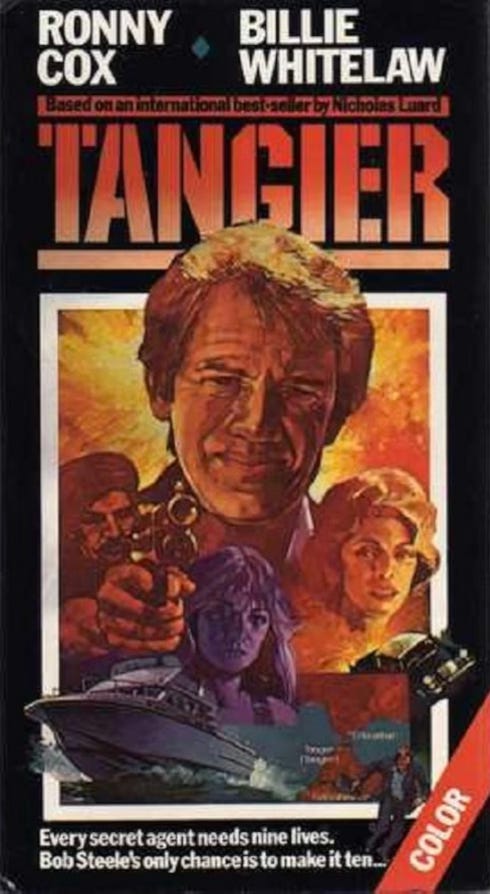

She made over 50 films. They included Charlie Bubbles and The Omen. And this one:

2.

Watching Beckett wander about Tangier in Banier’s photographs in 1978, I began to remember where I was that same year. I had moved to New York in 1975 to attend Juilliard’s Drama Division and was still an actor at that point. Alan Schneider was then in his first year as head of the Division having taken over for John Houseman who had founded it along with Michel Saint-Denis. I was in Group 8 and Schneider was one of the small coterie who watched my callback after my initial audition and offered me such longed-for affirmation and acceptance. Always a bit of an iconoclast, he only lasted four years at Juilliard before having a falling out with the administrative board and moved on, as did I after only a year. Schneider died in 1984 in London where he had gone to direct The War at Home, starring Frances Sternhagen, at the Hampstead Theatre. He was walking along a sidewalk. He had letter to Beckett in his hand. He was on his way to post the letter to Beckett’s address in Paris when he stepped off the curb into oncoming traffic having looked the wrong way forgetting the traffic runs on the opposite sides of the street in Britain. A motorcycle hit him. He was killed.

The first time I was aware of Frances Sternhagen was seeing her in the Broadway production of Equus in which she played Alan Strang’s mother. I was visiting New York from Mississippi for that audition for Juilliard’s Drama Division. After seeing it, my dream was to play the role of Alan in the play and I almost did so with Richard Burton when he took over the role of Dr. Martin Dysart on Broadway from Tony Perkins because Burton wanted to settle into the part before starring in the film version with Peter Firth who originated the role of Alan. I made it through several callbacks and down to the last three boys being considered. I was told by Bob Borod, the production’s stage manager, that it looked like the part was mine but I had to have a dinner alone with John Dexter, the production’s director, at Sardi’s after having had to visit him with the other boys at his home in Atlantic Highlands for one long, deeply odd and troubling afternoon. I write about even more of this scenario in my second memoir, I Left It on the Mountain, and why I didn’t get the role on Broadway and how I came to play it instead in several different productions once Borod had the power to cast it or was directing it himself based on Dexter’s staging.

1978?

I was in Providence, Rhode Island, playing the part of Alan in a months-long production of Equus at Trinity Square Rep with the company’s star Richard Kneeland playing Dysart opposite me and later that year in Philadelphia with Tony Perkins recreating the role. I had toured in a summer stock production of it with Donald Madden playing Dysart the year before. And a few months before that I had gone down to Atlanta to Theatre of the Stars to play the role of Alan with George Maharis portraying Dysart after John Daly, Tyne and Tim’s father, had to drop out for medical reasons. Daly died in 1978, in fact, during his preparations to play the role of Dysart finally in a production in Tarrytown, New York.

Edward Albee would become a friend during my subsequent years in New York - you can read more about that too in I Left It on the Mountain - and we were sitting around taking one day when I asked him what was the greatest performance he’d ever seen onstage, preferably in one of his own plays. I was waiting for him to say Uta Hagen in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? which was, yes, directed by Alan Schneider or Jessica Tandy in A Delicate Balance which Schneider also directed. But Edward surprised me. “George Maharis in The Zoo Story,” he said. “It remains the most brilliant of any stage performances I have ever witnessed.”

Edward’s The Zoo Story opened off-Broadway in 1960 at the Provincetown Playhouse. It was on a double bill with Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape, the latter directed by Schneider. Beckett doesn’t really write about kindness, or does so by giving space for its absence to exist so that we are concavely aware of the cavity where it could nest if it were actually needed. Krapp’s Last Tape is more about regret than being kind as the lone actor confronts the other cavity, the one of self, essential and, in this instance, spooled. In The Zoo Story, however, Edward deals with kindness head-on. Maharis, playing Jerry, gets around to talking to the other character, Peter, about it in a long and infamous monologue about his dog and if he has poisoned him or not, a kind of pilgrimage itself. “What I am going to tell you has something to do with how sometimes it’s necessary to go a long distance out of the way in order to come back a short distance correctly; or, maybe I only think that it has something to do with that. But, it’s why I went to the zoo today, and why I walked north … northerly, rather … until I came here,” the monologue begins before it winds its way to this: “I have learned that neither kindness nor cruelty by themselves, independent of each other, creates any effect beyond themselves; and I have learned that the two combined, together, at the same time, are the teaching emotion.”

I have instead learned - sorry, Edward - that in the midst of cruelty that kindness is the emotion that continues to teach me. So this week I baked my first orange olive oil cake here in Tangier. Baking it here meant something but I had to figure out what it meant so I turned to using it as a means to be kind in order to decipher that meaning. In Hudson, New York, where I once lived, I would bake my orange olive oil cake and walk down the street and give pieces of it away finding a strange comfort in being the eccentric old man who did so. Doing so and being such a person here in Tangier added an absurdist aspect to my being here as if I were a Beckett character stepping into an Albee play and running into Tennessee Williams in Amanda Wingfield’s kitchen, or Amanda in Tennessee’s. Baking that cake and being gesturally kind made Tangier feel more like home. So did the absurdity. I love being absurdly kind. I no longer have a home anymore but I do feel at home in that, the that I found here below in this.

Feeling absurdly at home somehow, I walked around Tangier and gave pieces of the cake to, among several others, Ali and Jane at the library annex of The American Legation. To Dr. Semlali and her assistants, Souad and Fatima. And to Ishmael and his older brother, Mohammed, at Coffee House where I often write in the morning.

Edward: "I'm not interested in living in a city where there isn't a production of Samuel Beckett running.”

I am more mundane. I’m not interested in living in one where I can’t read some Beckett while waiting for my cake to bake so I can give most of it away.

Never all.

I keep aside some symbolic essence of it to feed the real me.

Edward: “Beckett’s plays are inhabited by real people, not symbolic people. So are mine. Anybody is making a mistake if they think Beckett is writing about ideas rather than individuals. He’s writing about ideas, too, but his characters are three-dimensional. And Beckett is funny. I directed two of his plays at the Alley Theater in Houston. Ohio Impromptu and Krapp’s Last Tape. Fully three-dimensional. But bringing things down to essences, which is what Beckett was all about, is something we all ought to practice a little bit more … A playwright or any creative artist is his work. The biography can be distorting, or it’s just gravy. The work is the essence of the person.”

3.

SAYING DANTE ALOUD

by James Wright

You can feel the muscles and veins rippling in widening and rising

circles, like a bird in flight under your tongue.

Try saying these words below by Beckett, above on a Tangier beach, from his The Unnamable aloud like he and Whitelaw would do for each other when rehearsing his plays in private, each serving as the other’s conductor trying to find the right rhythm in order to go on. I found this while reading Beckett in the kasbah the other day as if I have been on this pilgrimage to it. I took it home. I read it aloud. I go on.

“I'm all these words, all these strangers, this dust of words, with no ground for their settling, no sky for their dispersing, coming together to say, fleeing one another to say, that I am they, all of them, those that merge, those that part, those that never meet, and nothing else, yes, something else, that I'm something quite different, a quite different thing, a wordless thing in an empty place, a hard shut dry cold black place, where nothing stirs, nothing speaks, and that I listen, and that I seek, like a caged beast born of caged beasts born of caged beasts born of caged beasts born in a cage and dead in a cage, born and then dead, born in a cage and then dead in a cage, in a word like a beast, in one of their words, like such a beast, and that I seek, like such a beast, with my little strength, such a beast, with nothing of its species left but fear and fury, no, the fury is past, nothing but fear, nothing of all its due but fear centupled, fear of its shadow, no, blind from birth, of sound then, if you like, we'll have that, one must have something, it's a pity, but there it is, fear of sound, fear of sounds, the sounds of beasts, the sounds of men, sounds in the daytime and sounds at night, that's enough, fear of sounds all sounds, more or less, more or less fear, all sounds, there's only one, continuous, day and night, what is it, it's steps coming and going, it's voices speaking for a moment, it's bodies groping their way, it's the air, it's things, it's the air among the things, that's enough, that I seek, like it, no, not like it, like me, in my own way, what am I saying, after my fashion, that I seek, what do I seek now, what it is, it must be that, it can only be that, what it is, what it can be, what what can be, what I seek, no, what I hear, I hear them, now it comes back to me, they say I seek what it is I hear, I hear them, now it comes back to me, what it can possibly be, and where it can possibly come from, since all is silent here, and the walls thick, and how I manage, without feeling an ear on me, or a head, or a body, or a soul, how I manage, to do what, how I manage, it's not clear, dear dear, you say it's not clear, something is wanting to make it clear, I'll seek, what is wanting, to make everything clear, I'm always seeking something, it's tiring in the end, and it's only the beginning.”

Onward .. (.)

Absolutely riveting.

Watching a Great Courses series of lectures called "What America's Founders Learned from Antiquity". Lecture 20 includes information about a Native American named Benjamin Larnell, who gained entry to Harvard in 1712 w/poem in Latin called " The Fable of the Fox and the Weasel". The moral was that people are happier w/o material possessions. (This made me think of you!) Unfortunately, he died at age 20. He was the fifth & last Native American to study at Harvard during the Colonial era. The lecturer is Caroline Winterer, PhD. Just a random observation... BH