“He sniffed at the fragments of mystery and again he felt an unaccustomed exaltation.”

- Paul Bowles, “The Sheltering Sky”

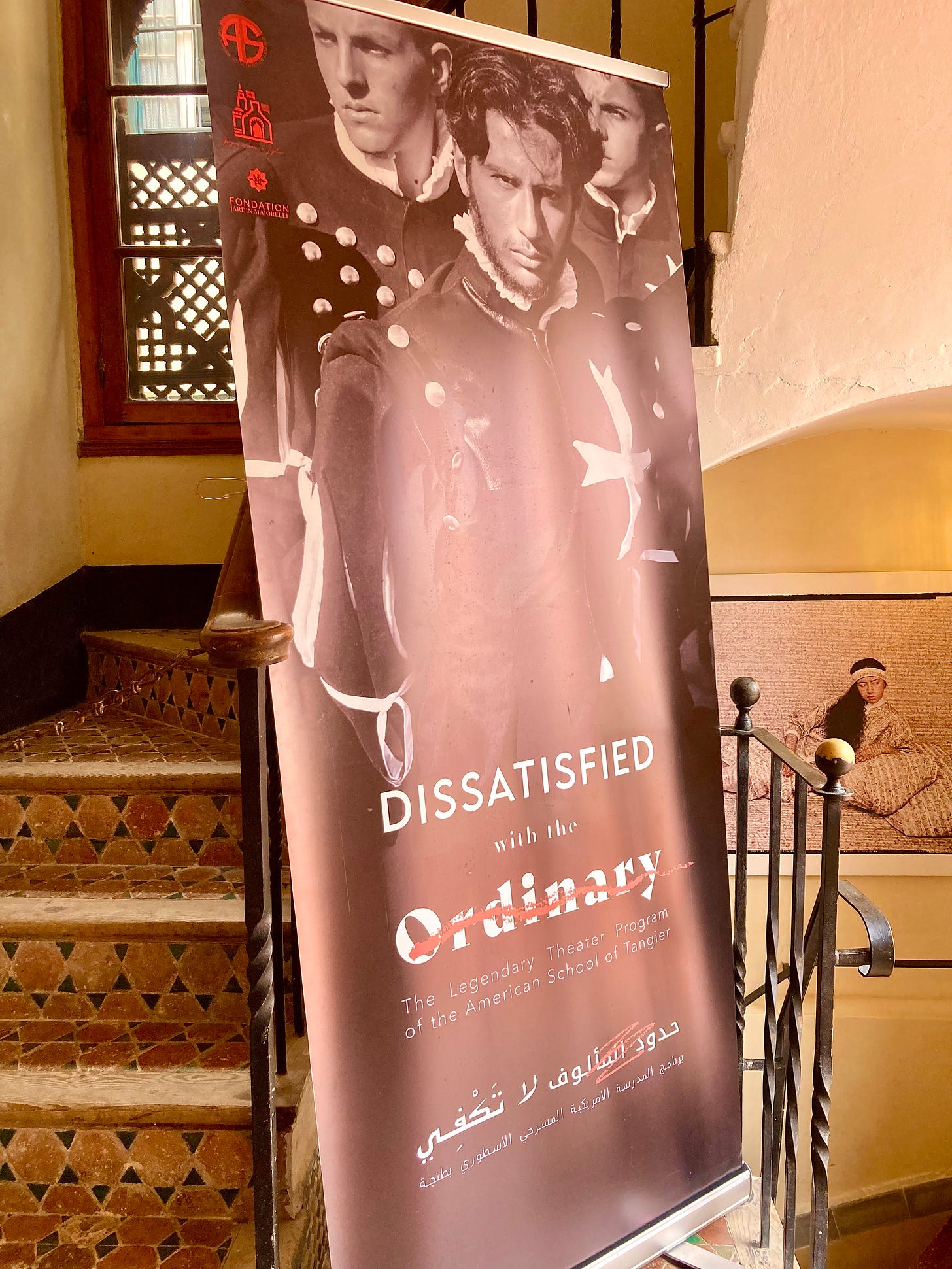

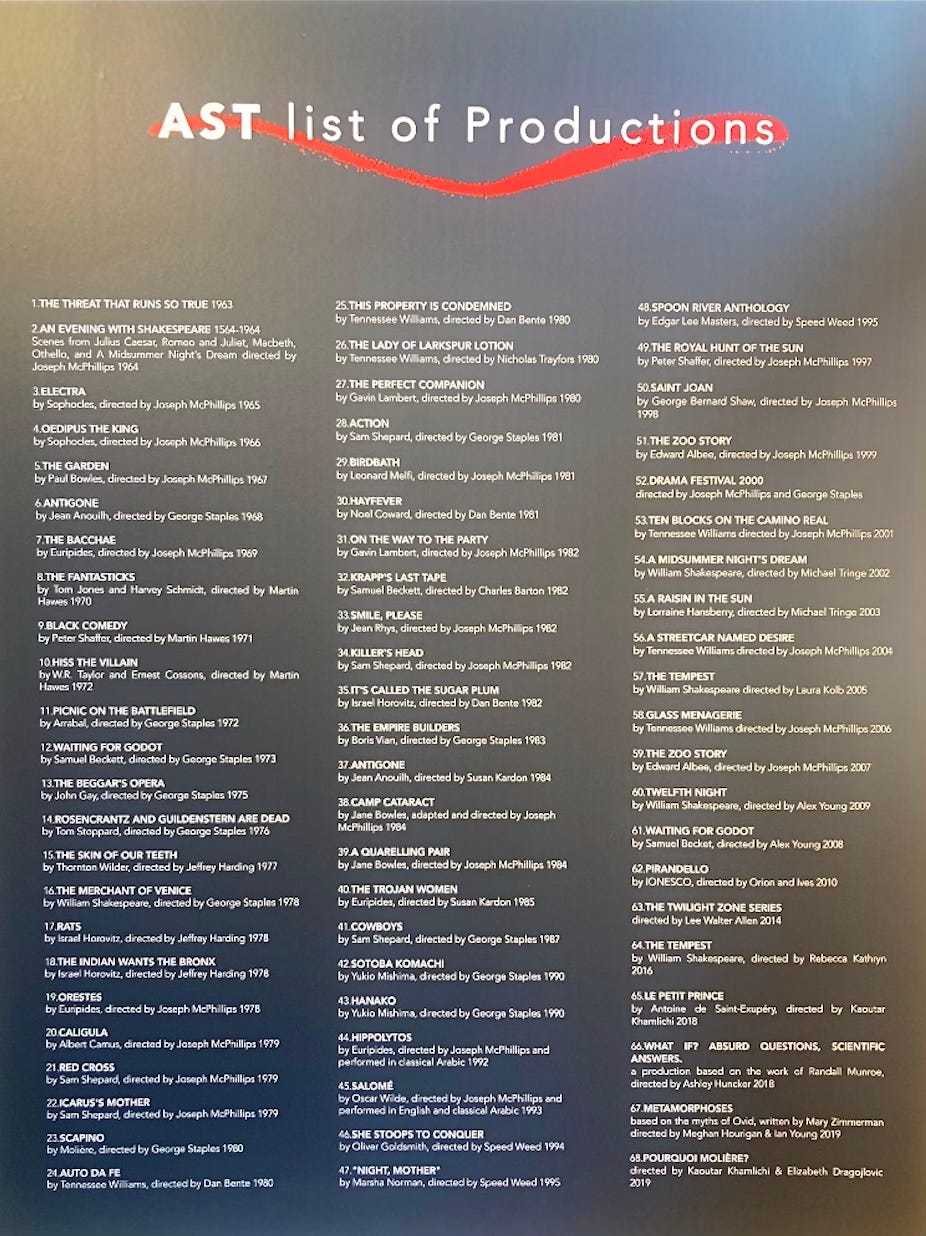

When I first got to Tangier last month, I headed to the American Legation above the Petit Socco to see the exhibition, Dissatisfied with the Ordinary, curated by Alexandra Kasmin and Karim Benzakour. It focuses on many of the 68 theatrical productions presented by the American School Tangier from 1963 to 2019. Presenting these plays was the inspired idea of Joseph McPhillips who originally taught English literature at the American School beginning in 1962 before becoming its Headmaster in 1973 until his death in 2007. He succeeded Omar Pound, the son of Ezra Pound and Vorticist artist Dorothy Shakespear. McPhillips directed over 20 of the productions himself sometimes with the help of two other Tangier residents, Paul Bowles who composed music for several productions and Yves Saint Laurent who designed costumes. McPhillips was so close to Bowles and his wife, Jane, that he became the executor of the Bowles estate at Paul’s death in 1999 until McPhillips’s own death in 2007.

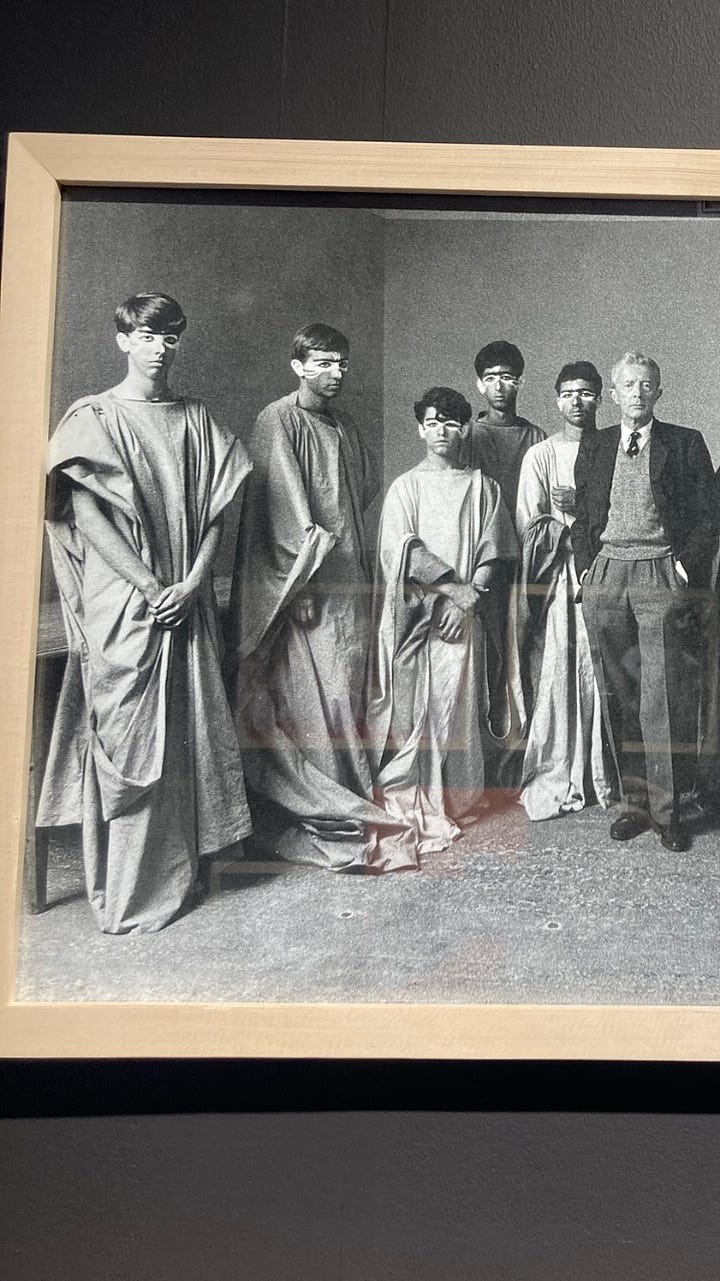

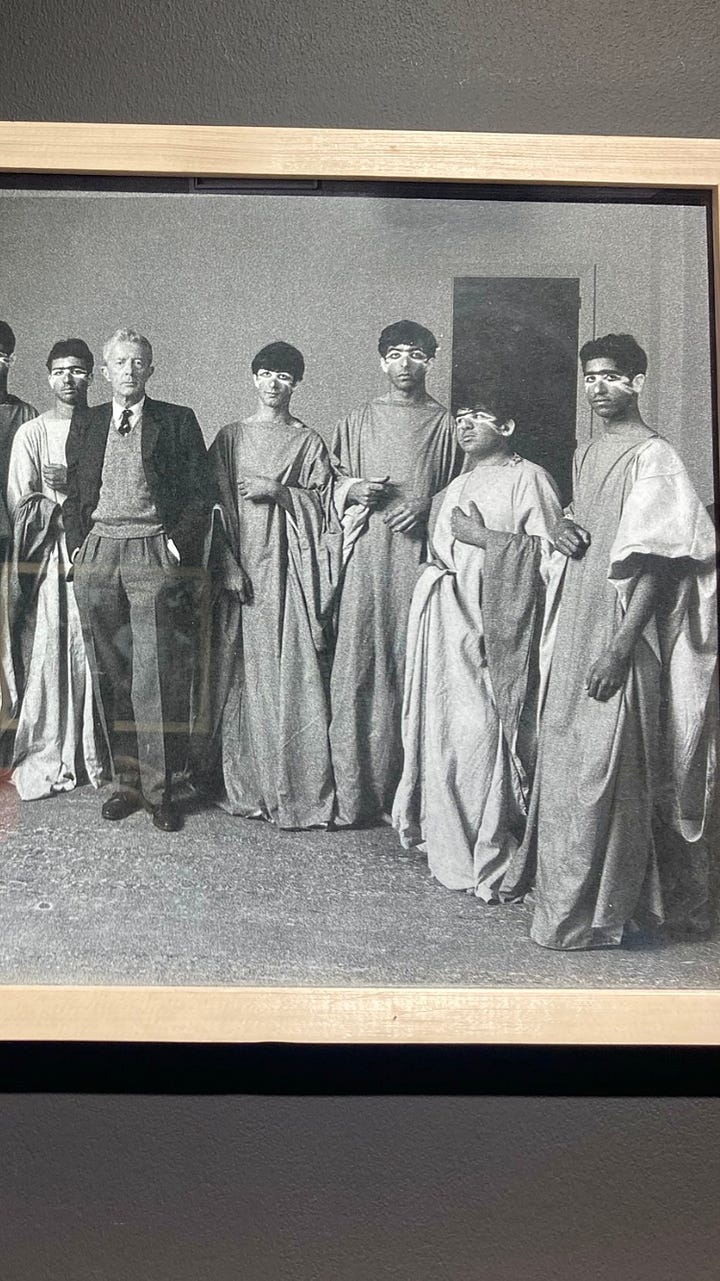

That’s Bowles above in a 1966 photo with the chorus from Sophocles’s Oedipus the King translated by William Butler Yeats for which Bowles furnished a bit of newer more Moroccan infused music that accompanied some of the text for the chorus which was also accompanied by music when the play premiered at the Abbey Theatre in Dublin in 1926. The New York Times, reporting about that initial production and its chorus on the day after Christmas of that year: “One does not expect to see an audience, drawn from all ranks of life, crowding a Theatre beyond its capacity and becoming awed into spellbound, breathless attention by a tragedy of Sophocles. Yet that is exactly what happened at the Abbey Theatre. . . . It was an event hitherto unequalled in the history of the Abbey, and when the chorus, standing before the closed curtain, spoke the concluding line, ‘Call no man happy while he lives,’ there followed a scene of enthusiasm surpassing all similar scenes with which the career of the Theatre is dotted. It was a spontaneous tribute such as almost beggared belief.”

Such a dispatch with a deleted reference or two could have been written about so many of the productions and the audiences here in Tangier over the many years that these student productions were staged. The works ranged from that Sophocles to Shakespeare to Beckett to Williams to Coward to Shaw to Camus to Wilder to Wilde to Shepard. The last choral line of the 1928 published text of Yeats’s interpretation of the Sophocles play is a bit different than the one quoted in the Times. “The dead are free from pain,” it reads in the version printed by London’s MacMillan publishing company. Either of the lines could as well have been written by Paul Bowles who, decadently dismissive even of his own despondence which could be sifted through a surfeit of surliness that he found perhaps rather silly, rarified, looked right back at time, that measurement embedded in the living, as something that hisses, outside. So much of the passive composition of writing is about actively listening. Bowles - so full of a kind of guile-laden passivity and puff after active puff of kif, the rascally old cool-ass literary coot who lay with louche elan about cushions covered in ash and rugs and reputation and who composed that latter-life persona with the care that he once put into a sentence - could even cock his prickly ever-randy ear toward that: time.

“There is a way to master silence,” he more precisely claimed, “control its curves, inhabit its dark corners, and listen to the hiss of time outside.” I do wish I had known the guy and sat in such dark-cornered silence with him in those two hours in the afternoon when he was receiving all others and, declining the kif, had listened along with him. That hiss though still hones itself here in Tangier because this is where time seems to have found a home where it too doesn’t have to be what is expected of it and can ignore us, the living, except for the two hours in the afternoon when it too receives all others to remind us and it that it’s here, still, outside, a hiss. The rest of it - time - we do tend to leave each other alone (but not quite) for it does, dammit, stare back in the satisfied acknowledgement of its being noticed without our really being able to touch it like the beautiful Tanjawi men who in their litheness seem to inhabit a liminal space between the masculine and feminine the way too time is lither and more liminal here.

I wish I had also known McPhillips. He was a gay man from the south like me - he from Alabama, I from Mississippi - who was both taken and taken in by Tangier because chief among his many lusts was wander. He was educated at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, before getting his BA in English from Princeton. His goal was to make the American School “the Andover of the Mediterranean,” he once told The Washington Post. “We provide an old-fashioned education. Students rise when adults come into the room. They read Lord Jim and Julius Caesar.” In 2001, McPhillips fulfilled a promise to Tennessee Williams to stage his play Camino Real down in the Petit Socco. The last play he staged was Edward Albee’s The Zoo Story.

There is a lovely story about the school and the productions and McPhillips in Vanity Fair’s March 1999 issue. It was written by Gavin Lambert - who had his play, The Perfect Companion, produced by the school. The photos for the Lambert article were taken by Bruce Weber. “A Princeton graduate from a well-to-do family in Alabama, the 26-year-old McPhillips had been living in Paris after having traveled extensively in Europe and Africa,” Lambert wrote. “Ezra Pound's son, Omar, who had just been appointed headmaster of the school, met McPhillips, who was a great admirer of the elder Pound, when McPhillips first arrived in Tangier. He had fallen under the spell of Morocco, but could not tolerate the lives of some of his fellow expatriates, who lived for the cocktail party, diplomatic dinner, or the next reception held by the Comte de Paris, pretender to the throne of France. McPhillips found an alternative to all the foolishness two years into his tenure, when a group of students suggested that he celebrate Shakespeare's 400th birthday by directing them in scenes from his plays. A tradition was born.”

I think McPhillips would have been quite touched by the remarkable exhibition at the Legation that has been put together by Benzakour who was the chief administrator of the American School from 1988 - 2021 and served as the stage manager for more than a dozen of the student productions. His co-curator Kasmin is a landscape and interior designer who is the friend who is letting me stay in her apartment for most of this summer. She is in the process of redefining herself much like time redefines itself here in Tangier by its being humbled by its own presence, a presence more deeply present than just the present, a deepness that delineates the past by not being it, storied, a living ore to be mined seam after seam after seem. No simile is needed, no “like the smoke curling from the kif-flecked lips of Paul Bowles’ mouth.” No metaphor: the pipe through which it’s smoked. It is but the bullying reality of the breath that the kif needs to conjure smoke from such a pipe. It is the breath that similes need. That a metaphor does. Time is a thing which is not. “You Are Not I,” I hear it hissing the title of a Bowles short story. It continues: “But I am you.” That story by Bowles is narrated in an act of transference by a dead woman’s sister. An act of transference needs both the active and the passive in order to occur. And maybe that’s what time is, just that: a dead woman’s sister. Or does that sound like bad Tennessee Williams spoken by a young Moroccan trying to approximate a Mississippi accent? Time’ll tell.

Director Rob Ashford is a member of the Board of Directors of the American Legation and ten years ago he and another Board member and a Trustee of the American School, Madison Cox, decided to continue the tradition of putting on theatrical productions in order to raise money for the school and the Legation and other charities. It’s odd that Chekhov was never done during McPhillips’s tenure. I wish he were alive to ask him why. This Saturday, however, Ashford is remedying that with a one-night only performance of The Cherry Orchard with a cast that includes Derek Jacobi, Kenneth Branagh, Gillian Anderson, Michelle Dockery, Luke Thallon, and Penelope Wilton. It is taking place after a dinner held on the grounds of designer Veere Grenney’s mountain estate. A stage has been erected for the occasion atop his pool. I spoke to Ashford in the garden of his own estate in town, which once belonged to YSL and Pierre Berger, for a story I have been assigned about the weekend and its events and told him that for a theatre nerd like me this production on Saturday is my version of going to a Beyonce concert. I’ll use some outtakes of our conversation for a LETTER FROM TANGIER once I’ve turned in the story and it's been published. The patio area where Rob and I sat was used for the first production he staged a decade ago, Williams’s Suddenly Last Summer. It starred Linda Lavin and Ruth Wilson and was performed for an audience of around 80 people in the lush garden of the estate that could, in fact, pass for the Garden District in New Orleans where that play takes place. This year around 180 are expected for the dinner and performance of The Cherry Orchard, a play which too lends itself to the gardens and the splendor of Tangier which is both faded and refurbished, remembered and newly owned, a tribal place, transactional, where prayers are called of the kind I do not pray.

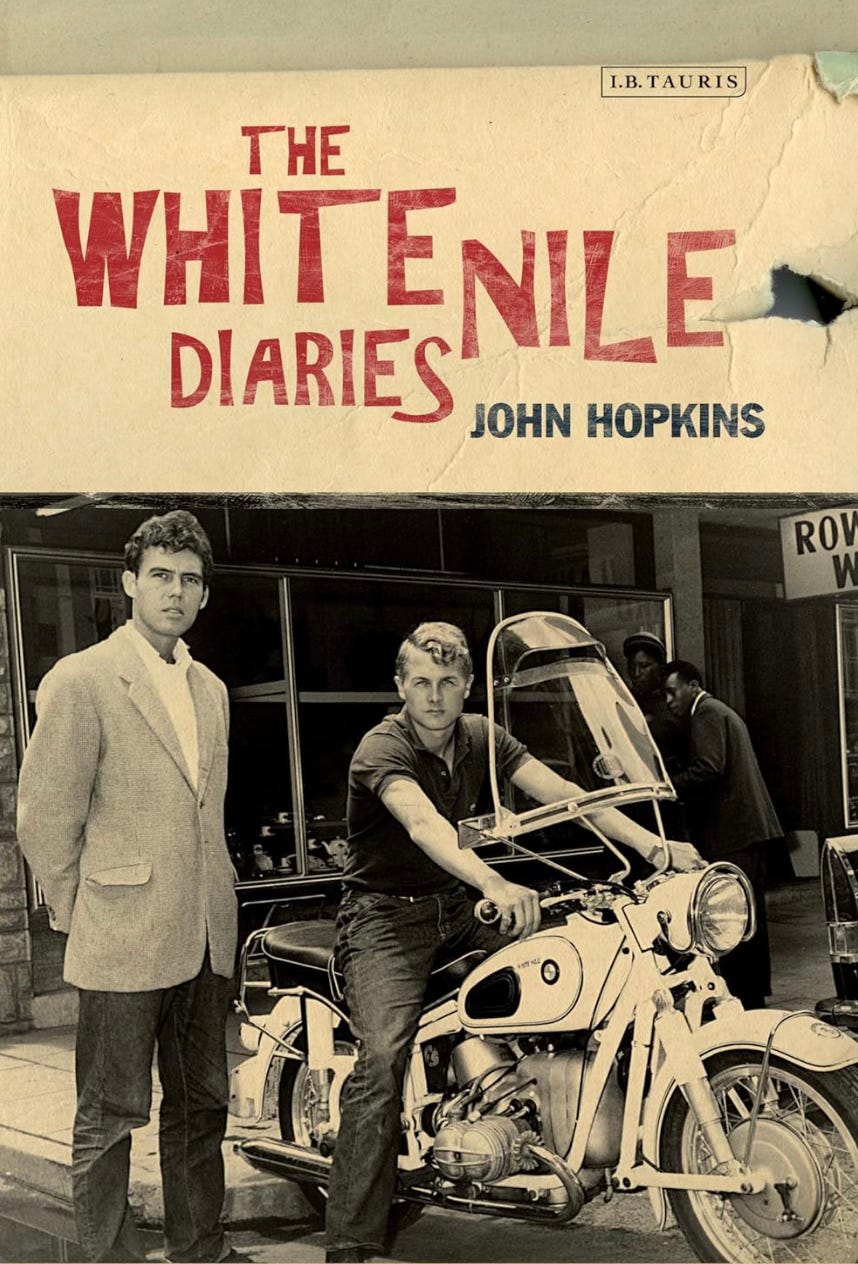

The sketch above by Yves Saint Laurent is for a costume for The Bacchae by Euripides which McPhillips directed in 1969. And that’s McPhillips on the left with his Princeton friend John Hopkins sitting on the bike which they christened The White Nile and took on a pilgrimage across North Africa before McPhillips settled in Tangier. My friend, Alexandra, who co-curated the American Legation exhibition has arrived this week to attend the many events along with “the tribe” as I call the folks from all over the world who have arrived to attend this annual weekend here of theatre and good works and art openings and dinners and parties. Our agreement a few months ago was that I would move out of the apartment when she arrived from her home in Normandy and back into the tiny room in the hostel where I stayed last year, a place where a different kind of tribe of travelers stays, the varied young who each night have their own kind of bacchanals fueled by hormones and their first forays away from what they have always considered home. Some are even on motorbikes and touring through North Africa in the tradition of McPhillips and Hopkins. Me? I am Cinderella who is going to the “balls” to report on them and then coming back metaphorically to sweep the hearth each night because the reality of my pilgrimage has bullied itself back into my life. And I’m fine with that. I truly am. Sometimes I am the lucky recipient of kindness living in a lovely apartment high above the kasbah and watching the moon rise over one of the apartment’s terraces. And other times I am the eccentric old man in a hostel full of European youth yearning for whatever it is the young still yearn for. I am the rascally old cool-ass literary coot listening to the hiss of time outside. It is my call to prayer.

Onward …

Looking forward to an update on the lovely folks at the hostel.

Ethereal excellence.