LETTER FROM TARIFA & TANGIER & CASABLANCA: 6/13/25

AMERICA IS ALWAYS IN THE SEAT BESIDE ME YET SO VERY FAR AWAY: Graydon Carter, Renewing My Passport, and No Kings Day in a Land Where There Really Is One

The picture above was my view from Cafe Colon on Rue de la Kasbah here in Tangier last Saturday which fell on Eid al-Adha, known as the Festival of Sacrifice. It is a major religious celebration in Morocco and honors the Prophet Ibrahim's willingness to sacrifice his son in obedience to God. King Mohammed VI issued a dispensation this year regarding the annual ritual slaughter of livestock and the sharing of the resultant feast with family and friends and those in need. After informing his subjects that they need not do so because of the expense involved which was a result of a drought that caused a paucity in the nation’s herds, he himself performed a ritualistic sacrifice for the whole country. Tangier was almost completely shut down on that first day of Eid al-Adha - the king also extended the holiday into Monday - but Cafe Colon down the hill from me was open so I sat at its sidewalk cafe in the eerie quiet and marveled in my own silence that my life had brought me to such a cafe on such a day in such a place. I went to take a photo of the cinema across the street and the poster for the latest film playing there but as I did so these two boys suddenly strutted into the frame dressed festively for the holiday unaware of Anjelica and Keanu et al. there behind them in the poster for Ballerina, a film about a cult and sacrificial killings and an underworld based on criminality not the need that all religions have to define evil in comparative and geographic ways.

Geography too has its own rituals. You can stay here in Morocco for 90 days without a visa but if you take the ferry over to Tarifa in Spain you can begin anew your 90-day count upon your return. You get to start all over - which is something that Americans of a certain eccentric literary ilk have been doing here for a long time, generations of our tribal lot with a penchant for perchance, purloined cultures, and colorful lives so often pearled with the whites of pages that await the saturation of rewritten sentences and narratives no longer related by rote. Tennessee Williams. Allen Ginsberg. Kerouac. Capote. Burroughs. Both Bowles. Mark Twain. Claude McKay. Even Edith Wharton swanned about although she had her own imperialist political reasons for doing so. James Baldwin was heading this way with his friend Norwegian journalist Gidske Anderson who decades later sat on the Norwegian Nobel Committee. They were so close that many in their close circle of expats in Paris at the time referred to her as his “fiancee.” Baldwin and Anderson were traveling to Tangier where he hoped to be inspired to write a short story he thought could be set here. But they missed their connecting boat in Marseille and decided to settle for a bit in Aix-en-Provence. It was a kind of preview of Baldwin’s later living in Saint-Paul-de-Vence “away from the American madness” where the “lucidity of distance,” as he described his perspective on such a troubled and troubling America, gave the sad sag in his eyes a keener, more contented cast.

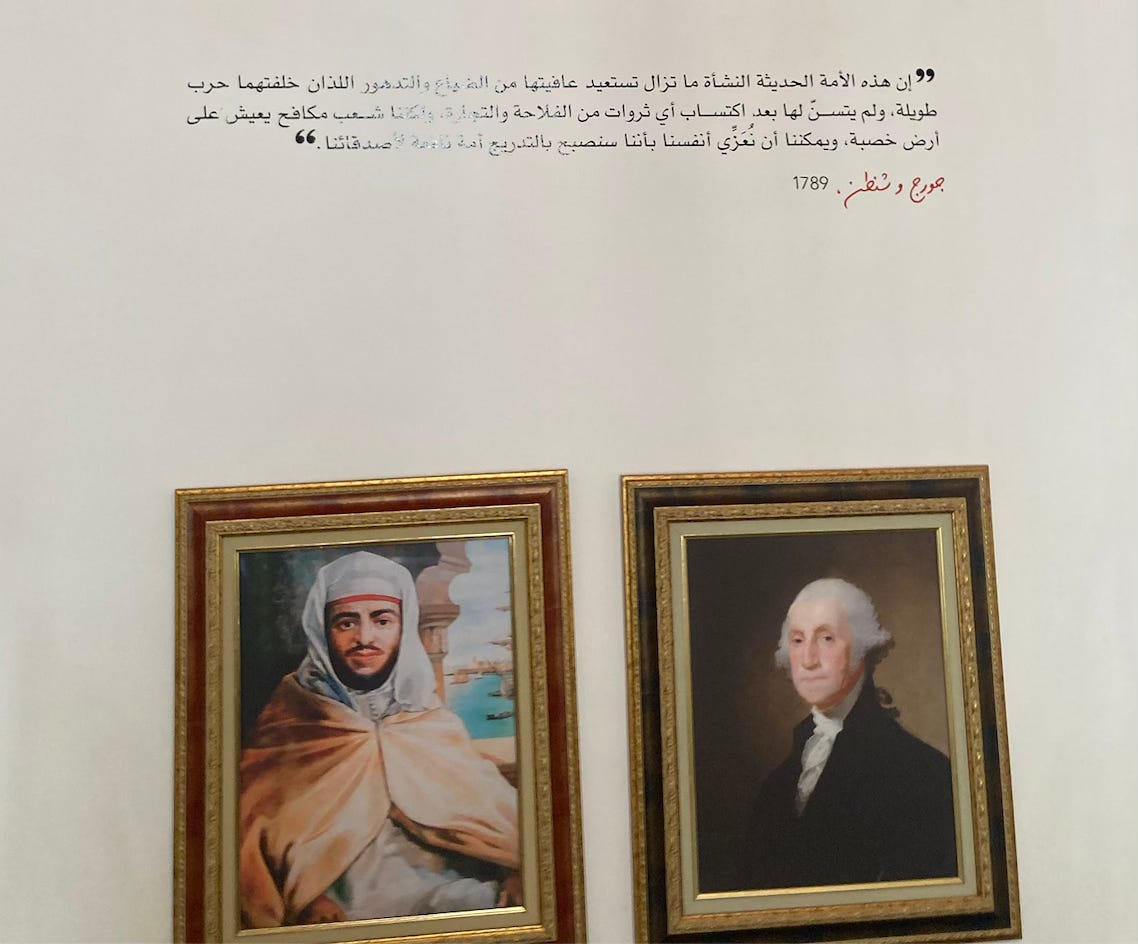

Morocco has had an unlikely side-by-side relationship with America since the 1770s when it was one of the first countries to recognize the US as a sovereign nation back when George Washington was its president. The American Legation here is one of the more fascinating discoveries I’ve made in Tangier where, having returned after a visit of a couple of months last year, I am spending so much of my summer. I love to visit the Legation - I’m quite fond of its Resident Director Jen Rasamimanana - and languish in its many rooms filled with art and history. There is a remarkable exhibition currently up, “Dissatisfied with the Ordinary,” about the theatrical productions presented at Tangier’s American School by its longtime headmaster Joseph McPhillips III, some with music composed by Paul Bowles and costumes designed by Yves Saint Laurent. I plan to write more thoroughly about the exhibition in an upcoming LETTER FROM TANGIER.

The beautiful building in which the Legation is housed was granted to the United States in 1821 by Sultan Moulay Slimane and it served as the official seat of American diplomacy in Morocco for 150 years. It is now known as The Tangier American Legation Institute for Moroccan Studies (TALIM) and functions as a museum and cultural research center and library. Once George Washington ascended to the presidency, he wrote a letter in 1789 to Morocco’s ruler at the time, Sidi Mohammed. An excerpt from that letter is printed on one of the stairwell walls of the Legation and translated into Moroccan Arabic along with Washington’s signature. It reads: “This young Nation, just recovering from the Waste and Desolation of a long War, have not, as yet, had Time to acquire Riches by Agriculture and Commerce. But our Soil is bountiful, and our People industrious; and we have Reason to flatter ourselves, that we shall gradually become useful to our Friends.”

Flattery might be a way into the dark transactional heart of the man who now leads an increasingly fascistic regime in Washington, D.C., but America can no longer flatter itself about being useful to its friends as the regime, on his orders, stiff arms those who once were friends while “the short-fingered vulgarian” offers such a hand to his fellow thugs and autocrats. He is useful to them, but as an idiot is. The quoted description of him was concocted by Graydon Carter when he and his editorial team were, in turn, concocting Spy magazine, that sprightly publication that would make fun of writers who used terms such as “sprightly” and “concocted” in such a context. The description has stuck - good - and still makes he-of-such-tiny-hands feel insulted, fidgety, aspersed.

I finished reading Graydon’s memoir, When the Going Was Good, during my travels this past week in Tarifa and then Casablanca where I went to renew my passport. The book was great company. It is brilliant in its breeziness which in its execution evokes a kind of effortless eloquence that not all who are so effortlessly elegant, as he is, attain after striving to find the place they can relax into being their truest selves when they’ve had to labor away at finding such a thing. The laboring-away early parts of Graydon’s life actually are the most charming and revealing and touching.

Graydon was my boss at Vanity Fair for many years and I wish I weren’t as intimidated by him as I so often was. I longed for his approval - still do - and sometimes got it but finally didn’t although a decade or so after our time together at Condé Nast he wrote me a lovely email about my work here on Substack, which I cherished. I admired him more than I liked him back during those Condé Nast days, although I like him rather a lot now. We are - through fallings-out and rapprochements- just different men. I wish I had felt more comfortable around him and didn’t myself stiff arm his early attempts at friendship so I could have asked him about his mother and father and early life in Canada, but the very subject of families has intimidated me as well since my own family history is filled with such trauma from my mother and father’s consecutive deaths during my childhood. And yet it is Graydon’s love for his family that has always moved me so about him. My own lack of one as a single gay man didn’t quite spark his disapproval but did cause him - my theory - to spurn me a bit and wonder perhaps about my worth. I was just not his kind of gay, or alas writer.

All that said, his presence is threaded through my past and that thread still holds. It hasn’t frayed. I’d put the book beside me on the ferry to Tarifa or the train to Casablanca or in a cafe chair in both places as well as here in Tangier after I had read a richly recounted section of it to contemplate my own New York existence that ran parallel to his. I’ve written about some of that in my second memoir, I Left It on the Mountain. Although I prefer my simpler pilgrim’s life now, I do at times miss a bit of the in-the-traffic excitement of those earlier American chapters of my own story. But like Graydon’s book, which is so full of anecdotes and even wisdom and seamed with kindness more than score settling, that part of my life is something I can now put beside me so that it, my American past, can run parallel with the grandness of the simplicity which now defines the pilgrimage where I reside in the wider world. I have come to feel such tenderness about my time at Vanity Fair from this perch sitting here typing this sentence at the cafe of Tangier’s Cinema Rif which itself is perched atop the Grand Socco where I am spending my mornings for the next three months writing and reading and watching this world parade by me. I like knowing that Graydon is probably across the way at his place in the South of France living his happy, full life with his beautiful wife, Anna, and a parade of their own of friends and expanding family. It’s hard for legends - and Graydon certainly now is one - to continue living such lives. Hell, he’s even found a way to oversee from overseas his airmail.news site. I’m in awe of the man’s navigation skills. Always have been. And have tried to learn from them although we continue in the comfort of our separate ritualized lives to map out geographies for them which are so divergent in, oddly enough, their sameness. That’s it. That’s what we finally share. We are each in our different ways just odd enough, it too an unlikely side-by-side relationship.

The book moved me to tears a few times - when he got his first big job at Time magazine, when his son Max, then 6, was badly injured, and when he stood up for his assistant who became his colleague, the divine and talented Aimée Bell, when she was being bullied by someone who was his own boss. I loved him in those moments and love - not just awe and admiration and the longing for his approval - became unexpectedly part of his thread-like presence still in my life. Who knows if I'll ever see him again. But love paired with absence has been the greater thread that moves through me so maybe I’ve just now been able to attach him to that. I am deeply grateful we shared those tender years at Vanity Fair and thankful he included me in the book as part of the roster of writers and reporters that he cited as a first-class lineup of talent. That meant a lot to me. He didn’t have to do that. Thank you, Graydon.

I do miss his Editor’s Letters when he was at Vanity Fair, especially when they’d turn political and take a stand. I wish I could read him presently with his monthly perspectives on it all although it would be hard to keep that kind of scheduled rollout of them which would be no match for the alacrity of the chaos unleashed daily by the vulgarian with all those short fingers in his realty show version of fascism.

I woke up Thursday morning to this headline:

When I read that - and later saw the stories about Senator Alex Padilla being manhandled and handcuffed by Homeland Security Secretary Noem’s thugs - the pang of guilt I can have about staying put away from the madness of America in this historical moment was not alleviated by the lucidity of this distance where I now spend my days. I think this weekend when the short-fingered vulgarian plans to get tanked-up with his martial parade but will likely be outmatched with the No Kings marches across the country will be an inflection point. When I was being driven to the train station to catch the Al Boraq high-speed rail service on Sunday to Casablanca from Tangier, I told my cab driver that instead of going home to a fascist America I have chosen to feel safer here in a Muslim kingdom. Irony is one of the first things destroyed by the MAGA movement - as it is in all fascist movements as they rise to power - but my sense of it has only deepened with this distance. I would have been raising my fist in a No Kings march if I had headed back to New York as I usually do each June and then on to Santa Fe for July, but instead here I am in a country ruled by a king. But he is a benevolent one whose sophistication and belief in science and education and museums - and high speed trains - is in direct opposition to the vulgar know-nothingness being unleashed in America by its destructive despot.

When I got to Casablanca, the gay hookup app I still have on my phone began to ping a lot. I just assumed that in Morocco the app would be blocked even though I had heard that Casablanca is where the LGBTQ community finds a more welcome home in a country - more irony - where being gay is actually illegal. I am not its kind of gay either. I didn’t answer any of the pings, however, because of a fear of being entrapped. I am illegal here and yet I don’t feel demonized like I do in America along with my transgender brothers and sisters. The literary litany I cited in my lede paragraph is made up mostly of the queer and queer adjacent and their presence here when it was even more dangerous to be gay and lesbian was always an important part of their being more bravely subversive than I in their art and in their lives. Another irony is that although I have decided not to have sex in Morocco because it just feels safer not to do so, I do find the men here quite beautiful. They are, in fact, rather androgynous in their beauty. It’s as if Kay Thompson were smoked though a Tiparillo and emerged even more elongated, limb-weary, lithe, tobacco-colored, ready to be inhaled again if anybody only had the gumption to try it. I just don’t personally have that gumption. Unlike Bowles and Capote and Williams and Ginsberg and McKay, I’m wary of their illegal limbs so wearied by their being desired by generations of such Americans. I wish I were more subversive. I wish I were braver. If I were, I guess I’d have to return to America in this moment to fight for it like James Baldwin did during the 1960s before heading back over here to this neck of the woods where he felt more at home, his need for one his most wanton of desires.

It was not lost on me either that in the midst of all these feelings I was in Casablanca to renew by passport by claiming my American citizenship. The consulate had canceled by earlier appointment for Monday because of the king’s extension of the holiday, but rescheduled it for early Wednesday morning. I worked up the gumption at least to flirt a bit with the elongated, limb-weary remarkably handsome security guard, one of many, who checked my backpack and confiscated the nail clippers I’ve traveled with for almost three years now. I think he, smiling in that way that signaled a bit more than bemusement, even flirted back. After I was told inside that the photo I had made in Paris a bit over a month ago was not the right size for a US passport and must circle back outside to get the correct photo in a shop around the corner with a monopoly on such mistakes, I had to show him my backpack once more before heading inside for a second time. He gave me that smile but was surprised to see me again. “I just couldn’t stay away from you,” I told him, making him smile even wider as he also beautifully blushed. Back inside, I handed over the new photos and had my forms stamped that I had already filled out and printed. It took less than a couple of minutes once I was at the window. I was told I would be receiving an email in around four weeks to come back to Casablanca to pick up the new passport. I had actually approached the morning with trepidation and the fear that I would have to go though an interview which would result in their seeing my social media posts and these Substack columns in which I decry the short-fingered vulgarian and all he and his fascist followers have done to continue to destroy America as a constitutional republic. I am happy it all went so smoothly but that fear which fascism relies upon had seeped into me.

I passed the handsome security guard again on my exit. We said our goodbyes. He wanted to know if it had all gone well. “It was all about being right-sized,” I told him referencing a tenet of recovery as I made a private joke about the photo I had to have reshot. “And surrendering to what I can’t control,” I continued. “I only had control over my reaction to everything this morning. I tried to remain calm in the chaos.”

His smile was more demur this time. “You are sounding like a Muslim,” I was told.

“Just a sober American,” I said now to myself as I walked down the street past the gigantic American flag that flew parallel to me in front of the consulate. “In this moment, a sober one.”

I took a photo of that flag.

I’m sure I did.

But I can’t find it now.

Onward …

Keep this up. It's so good.

This was a good way to start the day in beleaguered Los Angeles. Isn’t it an irony under the circumstances that the short fingered drooler turns himself a personal shade of brown each day before emerging from his crypt?