LETTER FROM VIENNA: 12/12/24

"WEST SIDE STORY," "TOSCA," OVERHEARD AMERICANS, CAFES WHERE TOURISTS DON'T TARRY, DIAL "HMMM ..." FOR MURDER, A SYRIAN, AND "THE EMPRESS" DUBBED IN ENGLISH

(Above: Karlheinz Böhm and Romy Schneider on a publicity tour for one of the trilogy of films they made together in 1955, 1956, and 1957 - Sisi, The Young Empress, and The Fateful Years of an Empress)

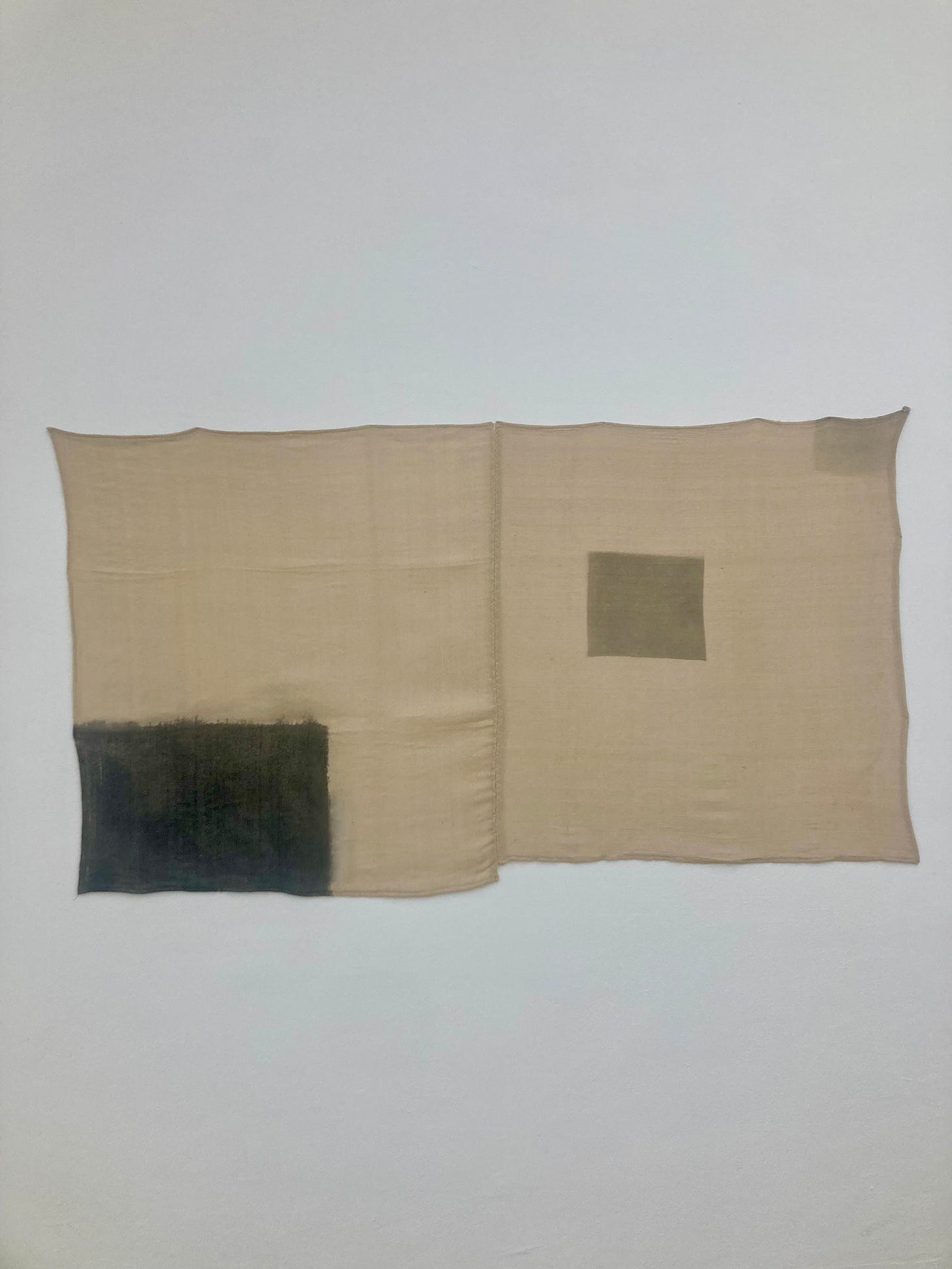

(Above: A work on sutured muslin from American artist Rochelle Feinstein’s The Today Show at Secession. It opened on December 6th and closes on February 23rd.)

(Above: Philip Froissant and Devrim Lingnau on a publicity tour for their Netflix series The Empress. Its second season began airing in November.)

Along with the German you hear spoken on the streets here from the locals, you also hear a lot of Russian and Slavic languages, that slur/on/a/slant of consonants clacking up against each other. You also hear a lot of the English that Americans speak, flattened, afraid of any kind of flourish of vowels while its volume is alas too bravely brayed into an icy breeze as they check their Google maps and debate directions toward the day’s next destination while standing in long lines at torted-up cafes which a guide book has convinced them they must try in order to have a seven-layered Viennese experience instead of putting down those guides and just getting lost in the architectural layers of the city and its achingly beautiful byways before somehow finding their way back from where they began. I want to tap them on their shoulders and suggest they head over to Café Prückel instead or burg.ring1 or goldener papagei or Café Weimar or Gaia Kitchen, a few of my favorites hangouts I have discovered on my own schweifenen about the city.

I have however begun to wonder, as I continue on this pilgrimage now more than two years into it, if I myself will ever find my own way back from where I began in that America of flattened vowels and sharpened differences because hearing the hum of Americans about me in Vienna during this Christmas season I have actually stopped tapping them on their shoulders to make suggestions or asking them where they are from because their white hum - and they are almost entirely white here in Vienna - no longer has the sound of home about it to me. I’m afraid I’ll be talking to a Trumper, a fascist with a festive air. One of my favorite things to do up until now, as I have traveled the world, has been to bond with Americans at crosswalks and cafes and when I, yes, find myself too standing in a line with them waiting to get into a theatre or museum. But I no longer engage with them unless they first engage with me. I just don’t want to face the fact that they might have voted for Trump - especially if they have a southern accent which could once elicit such a welcome sense of warmth within me. No more. I will not participate in the performative civility that would make me feel like a fascist collaborator, the howdy-how-y’all-doin’ the American version of a sieg heil, a conflation not of languages but of the latest blending of our histories. Eighty years ago we arrived over here to defeat fascism and liberate Europe from it. We are now foisting upon the world our own homegrown version, vulgar, dumbed-down, theocratic yet crass, an orange abyss of darkness. It arrives with guide books, camera phones, and the phony bonhomie of those who fear anything bohemian unaware that they are actually vacationing in the environs of Bohemia.

I know there are those visiting from America who don’t fit these descriptions and didn’t vote for Trump, and politically detest him and his seriously dangerous, deeply unserious fascism-as-reality-show-hucksterism as much as I. But this is the way I honestly feel even though I paint with too broad a brush - unlike American artist Rochelle Feinstein whose own broad bush is more intricate than mine, leaves room for more nuance, her cultural commentary more honed, hewn of hues instead of the clacking/on/a/slant array of black and white consonants and vowels here on the white hum of a computer screen, which is what is now called writing. Feinstein was until her recent retirement a professor of painting and printmaking at the Yale School of Art. Her work is on display here in Vienna at the Secession gallery space which describes her The Today Show as “a range of newly created works that circulate around the question of how to connect canvas, color and gesture with the specific personal and public conditions of our time.” Feinstein herself: “Humor, irony, sex, human stupidity, commerce, art, and politics are central to my inquiry. My work will not offer a placebo for trauma, self-care, healing, or depict illusory spaces. That is a task for others.”

I wonder if Feinstein will depict the young Italian American who recently murdered a health industry CEO in any of her future work and embed his shirtless torso in a collage on a canvas for viewers to discern as she does other cultural and political images and visages. Is this young man, in fact, a crime figure or a political one? He has certainly become a cultural marker. Even though Americans and their media outlets seem obsessed with him and this narrative of murder and greed, I wouldn’t have given any of it a second thought without the kid’s visual presence on social media or my having overheard him discussed as Americans waited in lines here in Vienna. I truly have no interest in him or the story and have posted nothing about about him on my own social media platforms. I could only muster a “hmm …” when I heard of the murder and then headed to another Viennese museum. It all seems very far away … because it is. It has, in its way, signaled a turning point for me on this pilgrimage. My lack of interest in any aspect of it has made me realize more than ever I am moving further away from America and not just farther. The task of taking it all to task - him, newsrooms, social media, American greed, the country’s broken health care system, manifestos, his abs and the absolution they seem to offer - well, that is a task for others.

Oh, I could feign interest in it all - the paragraph above it a bit of feigning - but it is both more than that and less: it is my dubbing my old American voice in for the one that is trying to find itself as this pilgrimage continues to help me discover and discern a newer one as a writer, more worldly without its being world-weary; that latter feeling, a mulch of the melancholic and choleric, had in its decaying insulation back in America become one of the main reasons I shook up my life and completely changed it, reconfigured it, swept it clean, by resetting its challenges from how to pay the bills to how simply to pay it forward inculcated as it steadily and more deeply becomes with kindness and culture and, yes, simplicity. I raked away the weariness by setting off rakishly into the world.

I have been shown several instances of personal kindness here in Vienna but when experiencing the cultural aspects of the city - especially offered by its famed State Opera House - that kindness has been replaced with an exacting officiousness that can frustrate this more freewheeling take on life that I now try to cultivate. One of the personal acts of kindness was a delicious dinner made for me one evening this week by a new friend (for whom I’m cat sitting in his gorgeous loft my last week here, more about that in a forthcoming Vienna letter) before my early curtain at the State Opera House for Tosca’s second and final performance with soprano Lise Davidsen (my favorite singer) in the title role and tenor Freddie de Tommaso as Cavaradossi. I had seen their opening night in this gloriously old-school production from 1958 with a ticket that was slightly out of my budget range and wanted to see them again. So I had gotten a cheap 18 euro ticket in a loge right above the stage but for a stool in the back of the box so it was almost impossible to see most of the action; it was more like a listening post, a perch where one could be enveloped with the lush sound of the orchestra there right below and the voices lifting up to travel over it toward the rest of the house. The loge’s location was right there in that aural uplift. “In any other house, I’d move to a spotted better empty seat during the interval,” I told my host at dinner. “But I learned my lesson when I was tossed from the House my first night there attending the ballet of The Winter’s Tale.” I continued to relate for him the wintry Viennese tale of my being embarrassed that first night by an usher (and my own effrontery regarding the precise adherence to protocol expected here) and escorted up the aisle with the whole theatre watching before the second act for my having moved to an empty seat on the second row. “A walk of shame,” I told him. He then offered some advice and suggested that during the interval later that I leave the loge and find an usher and ask permission to sit in an empty seat. “So they like to be in control and be the boss?” I asked about the house management and ushers who are employed by the government and not the opera and ballet companies. My host nodded in the affirmative and passed me some more potatoes … and cheese … and butter. So I later tried that ploy of politesse but the first usher laughed in my face and dismissed me with the wave of her hand after she had repeatedly excused herself to correct others who were not themselves precisely adhering to protocol as she checked their tickets and sternly shepherded them about. But I wasn’t ready to give up. I asked another usher on the other side of the house who understood English a bit better. She looked aghast that I would ask such a thing. “You must sit where your ticket tells you to sit. You cannot change your seat. That is not done,” she told me. “This is not allowed. Nein.” I then gave up and slinked back to my stool in the loge longing for the egalitarianism of French ushers who insist that people move to better seats before the curtains rise at theatres and opera houses in Paris, a completely different sort of shepherding, more share-and-share alike, or the welcoming demeanor of the British who, in my experience at the Royal Opera House, brighten more than bristle at one’s request to enjoy a performance from a better vantage point or knowingly ignore your stealthily having moved to a seat in the stalls. I steadied myself on my stool for Tosca’s second act. I closed my eyes and listened to the lift of voices. I left after “Vissi d’arte.”

I also saw an odd production of West Side Story at Volksoper where I had seen two wonderful productions of Fiddler on the Roof and Tick, Tick … Boom!. It was itself shepherded by Dutch opera director Lotte de Beer and choreographed by Puerto Rico-born New Yorker Bryan Arias. The fire escapes in the usual design were nowhere to be seen but gave way instead to a hulking black presence in the middle of the stage that turned and transformed and looked like something out of Dune. The opening scene was played under a billboard attached to one side of the hulking black spaceship-like presence, a billboard that advertised a pastel suburban dream home replete with picket fence. “Hmm ..” I thought as if I were thinking of a murder back in America - which was, come to think of it, the story that was about to unfold on the stage about 1950s New York City. The billboard was a directorial bit of foreshadowing for in Act II when Tony and Maria are supposed to sing “Somewhere,” it was instead sung in a dream sequence in which their imagined daughter sang it standing on the lawn behind the picket fence of that suburban dream house which had now materialized. The dream turned into a nightmare when all the preppie neighbors clothed in matching pastels who had been dreamlike in their civility up until that point erupted in a nightmarish Hieronymus Bosch-like - more Dutch influence - heightened depiction of violence toward each other until the discomfiting canaille of them all parted and revealed the little girl now with the dead and bloody bodies of Riff and Bernardo at her feet. The picket fence had been perverted, permeated; there was no escape from this no-more-water-the-fire-next-time America. There is none. James Baldwin might have rolled his weary, worldly eyes at this European reconfiguring of West Side Story. Jerry* and Steve* and Lenny* (with whom Jimmy was made a Commander of France’s Legion of Honor on the same day in 1986) and Arthur* would have probably sued which is the American way, wielding the law as a weapon which, in this case, would be to defend a work about lawlessness. That too is what Vienna is teaching me, how to accept its lack of irony about itself with my own deepening sense of the ironic. The audience received that reimagined bit of West Side Story with rapturous applause. I didn’t.

(Above: Maria (Jaye Simmons) and Tony (Anton Zetterholm/also portrayed by Cristof Messner) in West Side Story’s “balcony” scene played from Maria’s “fire escape” in the Volksopera production of the musical. Below: The poster alluding to the child who now sings “Somewhere.”)

My dubbing of my own American voice into this column a few paragraphs back reminded me that I have been listening to the dubbed voices of English actors Allegra Marland and Jack Bardoe in the Netflix series The Empress (Die Kaiserin) about the lives of Empress Elizabeth of Austria and her husband Emperor Franz Joseph. The lead German actors, Devrim Lingnau as the Empress (with Marland’s voice substituted for her own in my viewing) and Philip Froissant (with Bardoe’s substituted for his) are divine presences in this deeply romanticized - even fictionalized - account of those royal lives created by Katharina Eyssen. Sometimes the dubbing matches rather well and other times it’s a bit off. But because I watch a Netflix series late at night as I’m falling asleep, I don’t want to spend the effort to read subtitles on my MacBook screen. Lingnau and Froissant are so compelling as actors, however, and so finely cast, that I do want to hear their real voices and will listen to them this weekend and keep my reading glasses on as I fall asleep in a different way just as listening to dubbed voices is a different way of watching performances, faux limning the faux, an aural lifting of the voices - the stealing before the replacing, one sees the silence there beneath the sound - that lowers the acting somehow even though the dubbers are no doubt great actors themselves. In some way, I keep trying as well to decipher the stoic silence beneath the murmur of Austrians all about me but can’t quite make out what it is trying to tell me. The dubbing is just a bit off.

I was talking about this Netflix series the other night at the early dinner my new friend prepared for me. I told him that I thought it was what I should be watching while here in Vienna but that in my research since beginning it I’ve discovered that the real Sisi - as she was and is called, a name you see all around Vienna because she is considered a heroine of the empire a part of which this city likes to think of itself as still being - was much more troubled, although she was certainly an intellect. She had an eating disorder, was obsessed with staving off the aging process, and suffered from depression. “And she wasn’t as deeply, carnally in love with her husband as the series makes out,” I said. “That marriage seemed much more complicated and unhappy.” My host smiled. “Yes, she’s only been that in love with him since 1955. That’s when Romy Schneider played her. That became our Sisi.”

Lingnau who portrays her in the Netflix series is half Turkish. The great German actress Melika Foroutan, who portrays her mother-in-law, Sophie Archduchess of Austria , was born in Iran - as was the young hair stylist and club promoter I met who now lives in Budapest and was visiting Vienna. He spoke to me about politics and ended up defending Orban’s Hungary as better than Iran which was not much of a defense finally. I didn’t even try to defend America as I mentioned that Trump cites Orban as a leader he admires. This young Iranian who now lives in Hungary shrugged. “America is over,” he said. “It’s dead. America has died.”

I thought of his pronouncement the other night when I booked a Bolt car, the first I’d booked since my time in Tunis. The driver was from Syria. There are close to 100,000 migrants here in Austria from there. I told him I had been in Tunis and Morocco before coming to Austria. I then asked him if he ever got homesick for Syria. He turned and looked at me aghast at such a thought. “I am Austrian now,” he said. “Do you miss America?” he pointedly asked, trying to flatten his vowels to match mine. “The America I knew is dying,” I said, not ready to pronounce it dead like the Hungarian hair stylist from Tehran. “But I don’t miss it. No. The world is now my home.”

We then discussed what being a pilgrim means compared to what being a migrant does.

“Have you ever been to Cairo?” he asked.

“No,” I said.

“Visit Cairo,” he said with something that sounded like longing in his voice.

I return now to where I began. I think of the Egyptian actor Omar Sharif playing a Russian hero in Dr. Zhivago without the clack and slant of consonants needed since it was not filmed in Boris Pasternak’s language but that of a writer named … well … Bolt. Robert Bolt. “The path trodden by wayfarers and pilgrims,” wrote Pasternak, “followed the railway and then turned into the fields. Here Lara stopped, closed her eyes and took a good breath of the air which carried all the smells of the huge countryside. It was dearer to her than her kin, better than a lover, wiser than a book. For a moment she rediscovered the meaning of her life. She was here on earth to make sense of its wild enchantment, and to call each thing by its right name …”

Bolt:

“Gromeko: [Aghast while reading newspaper] They've shot the Czar. And all his family.[crumples newspaper.] Oh, that's a savage deed. What's it for?

“Zhivago: It's to show there's no going back.”

In the next days after the Bolt ride, I read so much about Syria which suddenly erupted into the news and about Bashar al-Assad’s having fled to live in Russia.

And I keep thinking of my Austrian driver from Syria who wanted to know if I missed America.

But there is no going back.

Not right now.

Not for the two of us.

That Syrian.

This American.

“ … Some day,

Somewhere,

We'll find a new way of living,

We'll find a way of forgiving.

Somewhere,

Somewhere …”

Everything connects.

Onward.

*The creators of West Side Story, Jerome Robbins and Stephen Sondheim and Leonard Bernstein and Arthur Laurents