PARIS NEWSLETTER: 11/1/24

LONGING AND BELONGING, POLLOCK AND PICASSO, A ROOSTER, TINA BARNEY, CALLS TO PRAYER AND FINDING OTHER WAYS TO PRAY

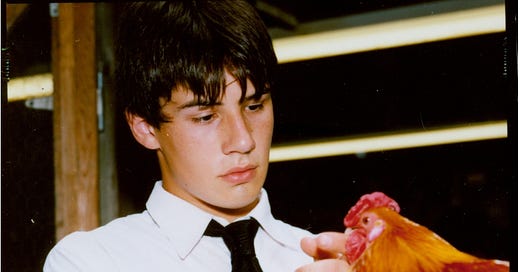

(Above: Jeune homme avec coq. 2011. Photograph by Tina Barney from her “Family Ties” exhibition at Jeu de Paume in Paris.)

1.

My new landlord here in Paris from whom I am renting a room stood in the hallway just outside the door of that room my first night here and we chatted in the way I learned to chat right-off-the-bat long ago in the bantam rooster phase of my career which resulted from my role as the go-to guy to write buzzy cover stories on celebrities at Vanity Fair, a chatty nonchalance that can shrug and shift and churn and charm with a performative intimacy I consciously choose to channel into it in an attempt to connect without being off-putting in my patter that can expose personal vulnerabilities and even harness a carefully delineated diffidence to give it all an undercurrent of buzz, a hum of humility. At one point I could weaponize honesty. But that was for professional purposes. I’ve kept the honesty unsheathed but no longer brandish it even though as a memoirist and now a Substack columnist it does in some ways remain my brand. Part of that brand is now being a percipient old pilgrim - which I prefer to elderly nomad - with notes of the wastrel still wafting about.

During that initial chat we were sussing out our roles as landlord and tenant as we figured out if their could be a friendship that finds its way into such a social contract since no official lease needed to be signed because mutual, yes, friends brought us together. We talked about being close in ages. “I love being older for lots of reasons,” I told her. “I really don’t feel any different than I did at 30 even though I am now more than twice that age. There is one thing though that does sadden me about being this age: I am no longer seen, or seen in the same way. But mostly just that: I’m not seen. I’ve grown to be okay with it finally,” I continued. “Because at a certain point in one’s 60s desire morphs into longing. I don’t have much sex anymore but I have lots more longing.”

She contemplated that.

Seemed to like the construct.

“I just want someone to hold my hand in a movie,” I confessed. “Truly that’s all I want. To sit in a cinema and have someone reach for my hand.”

She smiled at my confession.

Said some things herself.

She went back down the hall to the kitchen.

I placed the books and talismans I carry with me around the world on the desk in this latest little room.

I did not shut the door.

2.

The next morning I woke for the first time in two months not in Tangier and realized I had awakened on my own and not to the Muslim call to prayer and then a neighbor’s riled up rooster who heralded his not being a human who needs to pray. I never saw that rooster. Allah too aligns himself with the invisible. The call was broadcast from fuzzy loudspeakers so that a slight buzz was always there beneath it, a hum itself echoing the humility being demanded. The rooster’s herald had no need for manmade help. I grew to find the aggressive insistence of the calls to prayer prying open the horizon and the rooster’s more rudimentary rhythmic mocking of the break of day problematic. Preening. Just too damn noticeable, needy even in their musical, percussive demand to be noted, a mirroring of my own more mundane need for note. I did however find the duet of silence that abruptly followed the prayerful calls and those intervals between the rooster’s cocky ones deeper than the silence that I have taken for granted all my life. I lay in bed my first morning in Paris once more in a taken-for-granted silence and missed that other kind that had made itself known in Tangier. There are lots of absences in this life lived as a pilgrim - money, possessions, an outmoded idea of home. And there is a now here in Paris after my sojourn in Tangier a new one: a deeper silence I left back there.

3.

That first day here I headed to the Musee Picasso and its glorious exhibition “Jackson Pollock: The Early Years (1934 - 1947).” It runs until January 17, 2025. Do not miss it if you are in Paris. Jackson on his own pilgrimage toward his gesturally abstract drip paintings was, during this early period, greatly influenced by Picasso and Jungian analysis and his older brother, Charles Pollock, who was also an artist. These works in the exhibit were mostly a gestural mimicry of Picasso’s cubist genius which encumbered the younger Jungian Pollock until he poleaxed his way through it toward his own artistry - that tryst all artists have with themselves - and its mannered manly ejaculatory trajectory.

These early works ironically contained more cunning - paired with its lover longing - than the drip paintings which we can still come upon anew each time we approach them just as he seemed to have come upon them himself; they contain a sensuality - a kind of sexual consummation in their lack of precision as they envelope themselves and us in their thrust and flow - subsumed within the work that to me is a battle about submission. Is Pollock, bent but erect above the reclining canvas, submitting to it in the splattered ritual it is demanding of him or is its own submission to him in such a physically rejiggered artist-to-canvas relationship even more than the usual offering up of its purity to be defiled by the assertive strokes it takes to rend a beauty from it. There is in all art the redemptive act of the destruction of nothingness into something. We are both - it and us - soundly silent as we comprehend its incongruities and it ours. That’s its crux but not its fiction. There is a preening rooster’s herald held within such a duet of silence, a call to prayer humbly embedded there. It is carnal, and it is not - which is every human’s pilgrimage even if not an artistic one.

I honestly didn’t know much about Jackson’s older brother Charles so after the nod to him in the exhibition and his own mentor, Thomas Hart Benton, I read more about him and kept going deeper into his work and rummaging around until I found the connective thread from Tangier to Paris to this column. Katie White writing in Artnet.com about the Pollock brothers: “They ultimately turned to abstraction—the younger Pollock first, it’s worth noting—but whereas Jackson’s drip works took inspiration from Native American sand paintings, Charles was fascinated by the movements between figuration and abstraction found in some Arabic calligraphy.”

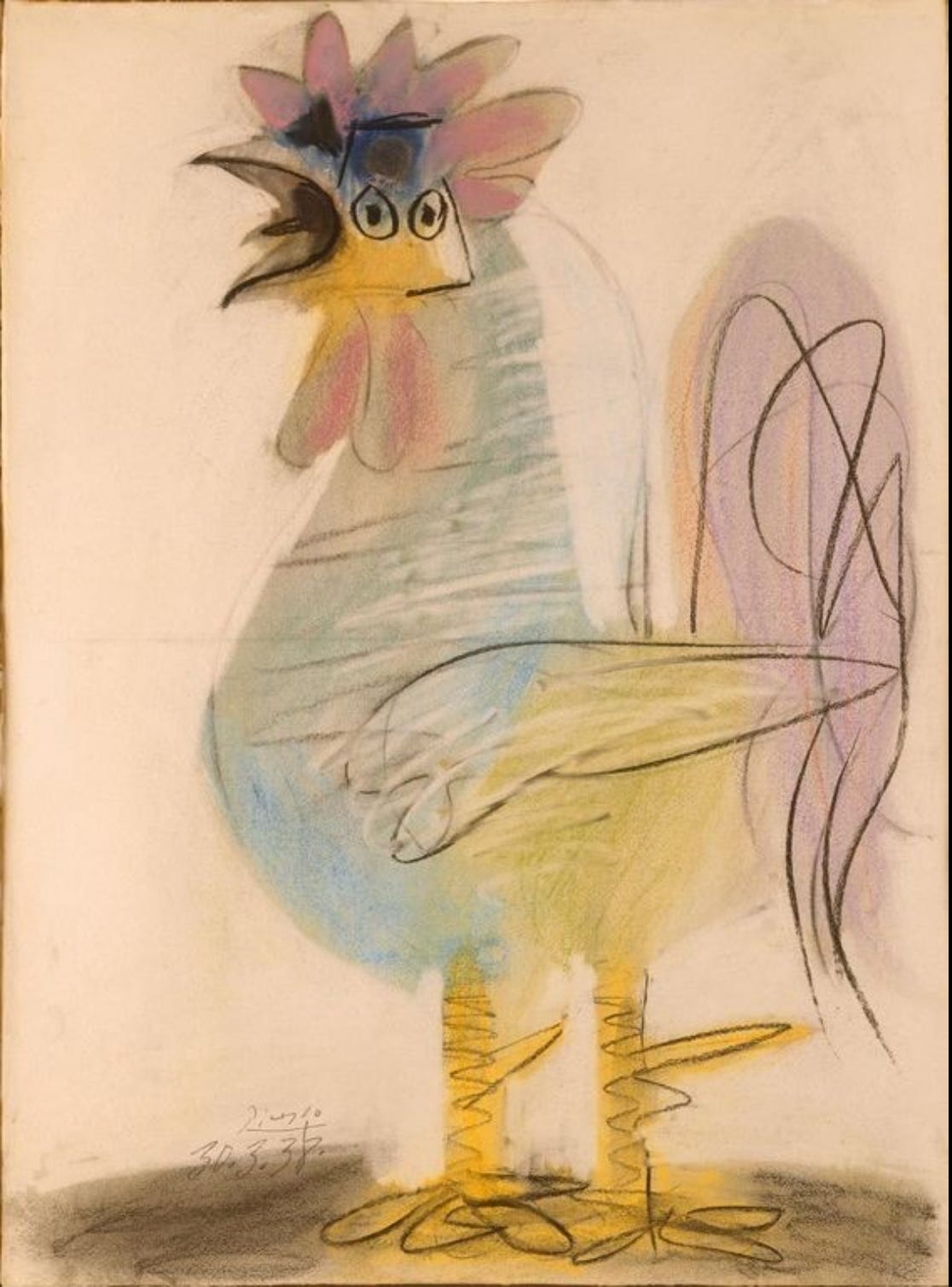

And Picasso himself while rummaging and rutting around for the loins and light he could rearrange in Paris’s arrondissements during this same time period highlighted in the Pollock exhibition seemed to have illustratively explored a kinship he felt with roosters - the strut as strategy - who for me in Tangier were - well, that one damn rooster - also imagined except for that one’s insistence. Picasso certainly created a lot of them. There is indeed an insistence to his assisting their insistence, these creatures who beckon the human concept of time, which might seem rather cubistic to them with their beaks and cockscombs and the thrill they give themselves for having feathered throats that wattle, that wail. They - like Pablo, like Jackson, like Charles - want the light, long for it in their holding forth. Look at me. Look at this. The insistence to be seen - to see the unseen within the seen - is what enables both religious rituals and a palette’s laying on of hands.

Wattle.

Wail.

Want.

Maybe that is what all art is.

And life.

That’s the pilgrimage.

Wattle.

Wail.

Want.

Cock-a-doodle-do(o).

(Above: Charles Pollock’s Rooster from 1947 is a better cubist one than any I could find by Picasso who was a bit obsessed by them. It is in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Below is one of Picasso’s.)

4.

There are also two great exhibitions at Jeu de Paume featuring the work of filmmaker Chantal Akerman and photographer Tina Barney. I spent a long lovely morning the other day at these shows - Akerman’s “Travelling” and Barney’s “Family Ties - and ended it at the Rose Bakery outpost located there. Akerman’s exhibition is about her own artistic pilgrimage as well as a very real one in Eastern Europe which she documented after the Iron Curtain and Berlin Wall fell. Barney’s work - she’s a scion of the hifalutin Lehman family - always seems to hinge on a captured banausic moment in a bigger, grander narrative of wealthy families and their friends, of hers, a tribalism of pastels and seersucker and dark paneling and East Coast picnics filled with towheaded children and tumblers refilled with gin. She is fascinated herself with rituals and the repetitive traditions which result in them. “The idea that families no matter where they come from, kind of do the same thing,” she’s claimed. Once when discussing an earlier show, “Small Towns,” she told The New Yorker, “In 2005, I was driving from my house, where I’ve lived since the 1960s, to Westerly, Rhode Island—a 15 minute drive. I realized I had overlooked this town where I’ve shopped for groceries, gone to the dry cleaners, fixed my car, gone to the bank, and repaired a watch. I began thinking about a new project to photograph. I was outside, which is rare for me, and I was also photographing strangers. But the communal act of repeating events over and over, year after year, that develops into traditions,” she continued, citing the similarities, “has always been the main attraction in whatever I seem to photograph.”

I began to make up some narratives as I viewed the Barney portraits - outside is not rare for me - which is my own repetitive ritual as I view art, pay witness to it, bond, meld - or, failing all of that, just move on. When I got to the portrait above that leads off this column - it was originally in the “Small Towns” show - I stood in silence and sounded out some ideas for that young man’s story but then realized it was the rooster that was riling me in the way the call to prayer could rile that one damn one back next door to me in Tangier. Standing in front of this Tina Barney photo was my call to prayer to prepare this column because writing is itself a state of one for me. I am in it right now typing this sentence on its own pilgrimage toward that period now nine words over from its having been named. It is an amen, and it is not - which is every sentence’s pilgrimage even if not an artistic one.

5.

I sat in the kitchen where I am staying this month in Paris late one night when I got home from the ballet and noticed this ceramic rooster perched high above me on this shelf. As I contemplated it, I more deeply contemplated the Tina Barney show I’d seen earlier in the day and my having manifested this life as a pilgrim, my tribe of one. So much of Barney’s work is about belonging. So much of my life now is about not really belonging anywhere but within longing itself. I am not a tourist there. I am not even really a pilgrim. It is where I’ve settled and the vantage point from which I write. And pray. And herald each new day.

A prayer - like a photograph, a cubist work of art, a drip painting, a documentary film, a life lived as a pilgrimage - is both a real thing and something that is created to understand the reality in which we live.

A rooster is a real creature even when it is never seen.

I longed for Paris in Tangier.

I miss Tangier in Paris.

“The human mind seems doomed to believe, as simply as a rooster believes,” wrote Barbara Kingsolver in Animal Dreams, “that where we are now is the only possibility.”

Now is also a settlement.

Here.

Now.

I’m here,

and not.

Onward …

I loved the specificity you got into about yourself at the beginning of this. More please.

Thanks, I needed that.