RECIPES & REVIEWS: 6/5/25

EDMUND WHITE, HONORÉ de BALZAC, PEE-WEE HERMAN, MOUNTAINHEAD, FOUNTAIN OF YOUTH, AND JUST LIKE THAT ... UN DERNIER REPAS de POMMES de TERRE SARLADAISES

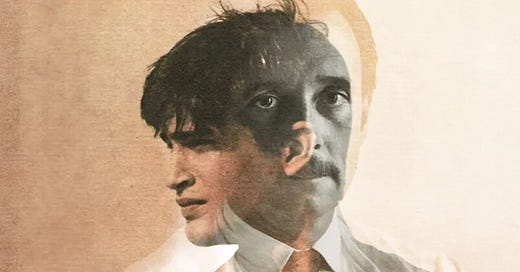

Above: A confluence of images. The “boy” from the cover of Edmund White’s memoir, A Boy’s Own Story, and White himself who died this week at the age of 85. The photograph, in one report I found, is supposedly of a fourteen-year-old boy, Robert L. Rosen, and was taken by photographer Dan Weaks after a chance encounter at Cape Canaveral in the early 1980s. The photograph of Ed was taken by Robert Giard in 1985.

Below: A confluence of writers. White and I at a run-through for the 2015 Lambda Literary Awards ceremony in Manhattan. Because every queer writer who has come of age since the 1970s and found each of our voices does so - and will always do so - in White’s wondrous prolific confluent wake. I had received the Award in the Gay Memoir/Biography category in 2007 for my own story as a boy, Mississippi Sissy. I was there in 2015 at the ceremony to present the Award in that category and Ed was one of the nominees for his book, Inside a Pearl: My Years in Paris, and was there as well, I think, also to be a presenter. But the Award that year in the Memoir/Biography category went to two books, John Lahr’s Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh and Richard Blanco’s The Prince of Los Cocuyos. Ed spoke at the first Lambda Literary Awards in 1989, won in the Gay Memoir/Biography one in 1994 for his Genet: A Biography, received its Visionary Award in 2018, and was nominated many times. I didn’t know him well, but I did because of his books.

I heard about White’s death yesterday here in Tarifa, Spain, where I have settled for a few days recalibrating my 90 days allowed me in Tangier this summer because you can leave Morocco for a day or two and upon your return your 90-day count begins anew. So I hopped the ferry yesterday for the 50 minute ride here to Tarifa and will return on Saturday. I had thought I might put up a recipe for something with this lovely little seaport’s red tuna in it but the sad news of White’s death made me change my mind. I googled “Edmund White’s favorite meal” and this is what came up as the first suggestion in the AI OVERVIEW which is now how my computer labels its response to my searching for something: “Edmund White's favorite meal, as described in his writing, includes a variety of items. He enjoyed a boiled egg in the morning, sometimes with sardines mashed with butter. In the evening, he might have a chicken wing or roast lamb. He would often end his meals with black coffee without sugar.”

I thought: Hmmm … I didn’t know you well, Ed, but that doesn’t quite ring true.

So therefore allow me to start this column today in gratitude to Edmund White’s ghost-like presence - still poetic, still mischievous - circling here in Tarifa to tell us how strictly dumb AI can be. And yet, in some way, AI’s untrustworthiness and its lazy mistakes just might be what make it alas even more human instead of just being human-like. Maybe White - not ghost-like at all, but truly ghostly - was just having a little fun with his own even deeper confluence in death with Balzac, one of his favorite writers while he was alive. Or perhaps this was a disembodied signal they were passing through the disembodied intellect of AI and then through my own needs here in this column that they have finally met not-in-the-flesh within a metaphysical mashing together, their mingling resulting in this morning’s warm breath of a breeze having brought this forth, the pneuma demanding to be noticed, measured deaths the buttering up that some other realm needs in its own recipe to exist where we who are alive both do and do not, a confluence we’ll someday more deeply understand, the mashing together of all this matter that we think matters with what is not and really does.

Or something like that.

Okay, Ed, I’m getting to it.

Okay, man.

Men.

Or whatever you both now are.

Wherever.

Let me more simply explain.

My instinct correctly told me to keep looking for a meal Edmund White might like other than sardines and a boiled egg.

This is what I found next since I have a digital subscription to The New York Review of Books. In January of 2012, he wrote a review - an appreciation really - of French writer Anka Muhlstein’s Balzac’s Omelette which had been translated by Adriana Hunter. Here is how it began.

A HUNGRY LITTLE BOY

by Edmund White

The preconceived notion might be that Balzac was a gourmand, a modern-day Gargantua, excessive in his feasting as in his writing and his socializing and his consumption of coffee and his pursuit of titled women. Just look at Rodin’s nude study of him, with his Jovian girth and prominent belly. That’s the image most of us have of Balzac—and it seems it was fairly accurate since Rodin, some forty years after Balzac’s death, had his old tailor make to measure a set of his clothes so that the sculptor could have an exact sense of the writer’s body. Not only do we imagine that Balzac ate to excess. We also expect his Parisians to be gorging themselves indiscriminately on all the rich foods of the world, prizing fruits out of season and grating truffles over everything and downing hundreds of oysters.

But it’s a very different picture that Anka Muhlstein presents, one that is more nuanced and contradictory and surprising. Most of the Parisian women of fashion in Balzac’s era (and books) are on diets. Only the Princesse de Cadignan understands that to attract her lover, who loathes affectation, she should eat heartily. As Balzac tells us, “In Paris people eat [half-heartedly] and trifle with their pleasure.” No one ever comments on the food, which is assumed to be uniformly excellent.

It’s still that way. I can remember when I first moved to Paris how dismayed I was that no one ever praised my carefully prepared meals except when I offered seconds; then they turned down another helping but murmured that it was all very good. It took a while to learn that the fiction, at least in the past, was that everyone had a famous chef in the kitchen and it was pointless, even a bit insulting, to compliment the host or hostess on the food. One flustered woman even said to me, when I assured her that everything was excellent, “Don’t look at me—I didn’t cook it!” Muhlstein tells us: “In society, people do not go out to enjoy a delicious meal but to do business, to conspire, to hear the latest news, and to make sure they are seen.”

Another thing that hasn’t changed in nearly two hundred years: the French, then as now, dislike the smell of cooking and esteem the visual presentation of food above its taste. Whereas we think it’s cozy and welcoming and mouth-watering, they find the odor of warmed food revolting. James Rothschild, the founder of the French branch of the banking family, was so determined that cooking odors would not disturb his guests that he had the kitchen situated far from the château and the food delivered by a little underground railroad. His chef was Carême, the most famous culinary genius of the day, who specialized in pièces montées—complex architectural table decorations that represented castles or parks and presented lobsters holding up a statue of Diana, say, or cream puffs stuffed with fruit and placed as cannons on a royal barge. Though these creations contained food, they were not meant to be eaten. Carême, who’d studied to be an architect, said that pastry was the highest form of architecture.

To get a good meal, in Balzac’s world, the characters must go to the provinces. There they may not have the same choice of luxurious foods but the ingredients, at least, will be fresh. In this way Balzac was a bit like us: he prized fresh food served simply. He didn’t like elaborate sauces. For him a simple dish of haricots verts could be the acme of a healthy meal, whereas a later chef, Escoffier, thought the glory of French cuisine was that no ingredients were recognizable after they’d been prepared and cooked. Muhlstein defines Balzac’s culinary ideal as natural ingredients with no spices added whatever.

Balzac, we learn from Muhlstein, didn’t know any celebrated chefs and therefore had no inside information about their métier. He never observed a great chef at work. He describes the actual procedures of only one cook, the aunt of Vautrin, and she mixes poison into dishes intended for her nephew’s enemies. Balzac, who loved to study techniques, crafts, and arts and could describe them at length in his novels, actually knew very little about cooking. He ate abstemiously when he was writing for fear of overworking his digestion, “to avoid wearying the brain,” as he put it. During his intense, prolonged bouts of composition all night long and well into the day he drank only water and coffee and ate nothing but fruit. Muhlstein adds:

Occasionally he took a boiled egg at about nine o’clock in the morning or sardines mashed with butter if he was hungry; then a chicken wing or a slice of roast lamb in the evening, and he ended his meal with a cup or two of excellent black coffee without sugar.

His death has been attributed to caffeine poisoning. Certainly he took coffee seriously and spent much effort looking around Paris for the three different beans he needed for his special blend. And he no longer boiled coffee as they did in the provinces; he had an elaborate filter pot to prepare it. Tea was so rare that it could be obtained only at the pharmacist’s. (To be continued …)

###

I read the rest of the appreciation - how could one not? - and then, after discovering the AI’s dumb mistake, kept looking for something that Ed might like to see as a recipe here. So the third thing I landed upon was the Questionnaire that Graydon Carter’s Airmail.news site poses to a keenly curated lot. White answered it back in February of this year. In it, he claimed that he wished his final meal to be potatoes in duck fat. I’d found what I’d been looking for. So Ed, this RECIPES AND REVIEWS column is in honor of you this week - and, okay, okay already, you guys - in honor of Honoré too. Rest in peace, you two.

[TO READ THE RECIPE FOR THIS DISH AND THE NEXT PORTION OF WHITE’S APPRECIATION OF BALZAC’S OMELETTE, AS WELL AS MY THOUGHTS ABOUT MOUNTAINHEAD, AND JUST LIKE THAT …, FOUNTAIN OF YOUTH, and PEE-WEE AS HIMSELF, PLEASE CONSIDER JOINING OUR PAID SUBSCRIBER COMMUNITY FOR ONLY $5 A MONTH OR $50 A YEAR. THANKS SO MUCH.]