REMEMBERING FRANK HAINS

THE MISSISSIPPI MENTOR I FOUND MURDERED WHO GAVE ME THE LIFE I AM NOW LIVING AS A COLUMNIST IN AN EVER-WIDENING WORLD

The photo above is of Francois Truffaut’s grave I visited recently in Paris where I have two more weeks to go in my two months of living here before returning for another two months next spring in this pilgrim’s life I am now leading. I had been wandering around Montmartre Cemetery in one of those unplanned spans of a few hours that can occur here in Paris when you set out as a flâneur and find yourself ending up where you were going all along. I stood staring at the reflections in the black stone and as the tree branches bristled in their longing for this present spring more fully to arrive and the clouds floated by like the smoke from Catherine Deneuve’s too carefully flared nostrils noticing yet again what she had inhaled into her body from a 1968 cigarette she had bummed from a technician between takes while filming Truffaut’s La Sirène du Mississipi, I put the “p” back into the last word in that title and, standing in a cemetery in Paris, reflected on the first 19 years of my southern gothic sissy existence in the deeply southern state which I spent in too many cemeteries reflecting on death and longing - bristling even - for a life that could lead me to Paris in search of a lost consonant in a language I could not speak but spoke to me nonetheless. It is a disorienting loop, this living within a world that keeps trying to translate us sissies into its own existence as we try to translate it into ours within which we, in turn, no matter our ages, stumble around trying to find a semblance of balance in the semantic ballast that we are told bigotry gives to our lives strengthened for having to survive it. I have always reveled in my own one-off quality, either being that young Mississippi sissy longing for the wider world or now an elderly pilgrim living within an ever-widening one as I am intent on ever-widening it for others I meet along the way. I have never felt at home anywhere really but I have felt oddly at home here in Paris these last couple of months and maybe that is because the way I have always spelled Mississippi is not the way it is spelled here. An inversion of correctness can occur in Paris. It’s why American outcasts have historically recast ourselves here in its roux of rue and rues, the former reconfigured as we roam the configurations of the latter. Even the “ending up where you were going all along” of the flâneur is a way of being correctly incorrect here. I have always felt a kinship with that lone, mirrored, beside itself “i” trapped inside Mississippi, but reflecting at Truffaut’s grave the other day as the simile of Deneuve’s cigarette smoke found its place in the natural order in such a place, I felt a kinship with the incorrect consonant in Mississipi that had correctly gotten away. It might not have been the normal way of doing so, but I too found my place in the natural order. And I did not reconfigure myself within the configuration to do it. I am both the vowel that stands its ground and the consonant that left - that leaves - seeking other words. I am not spelling. I am language.

Back in Mississippi when I was that 19-year-old boy figuring out that I was a consonant who could leave the fold of its word, I was introduced to the films of Francois Truffaut by my first mentor, Frank Hains, who was the Arts and Entertainment columnist and editor at the Jackson Daily News, the afternoon newspaper in Jackson, Mississippi, where I was attending Millsaps College. In 1974, Truffaut’s Day for Night was playing at the Lamar Theatre downtown. It had won the Best Foreign Film Oscar in 1973 and then in 1974, after being released in America, it was nominated for Best Film and Truffaut for Best Director. It also won the BAFTA and NY Film Critics Award for Best Film and Best Director in those two separate years, the former in ‘74 and the latter in ‘73. Roger Ebert called it the best film ever made about the movies. Pauline Kael liked it well enough in her Kael-ish way calling it "a return to form" for Truffaut, "though it's a return only to form." Jean-Luc Goddard walked out of it and despised it and called it a "lie." A cultural kerfuffle ensued with Truffaut writing Goddard a long public letter in his own defense. It is reported the two friends never talked again nor saw each other.

Frank adored this film and as part of his mentoring me insisted I go see it at the Lamar Theatre. So I did. I told him I liked it but I wasn't sure why and it was a bit over my head. He told me it was no such thing and to read up on Truffaut and go back and see it again. So: I did. I too then adored it. Jackson was still a place - thanks to Frank and his dear friend, Eudora Welty, and others during that halcyon time when I was so lucky to be cut out of the herd as a teenager and included in their sphere of culture and kindness and clinking glasses filled with Maker’s Mark - where a theatre downtown played Truffaut films and an audience showed up to watch them.

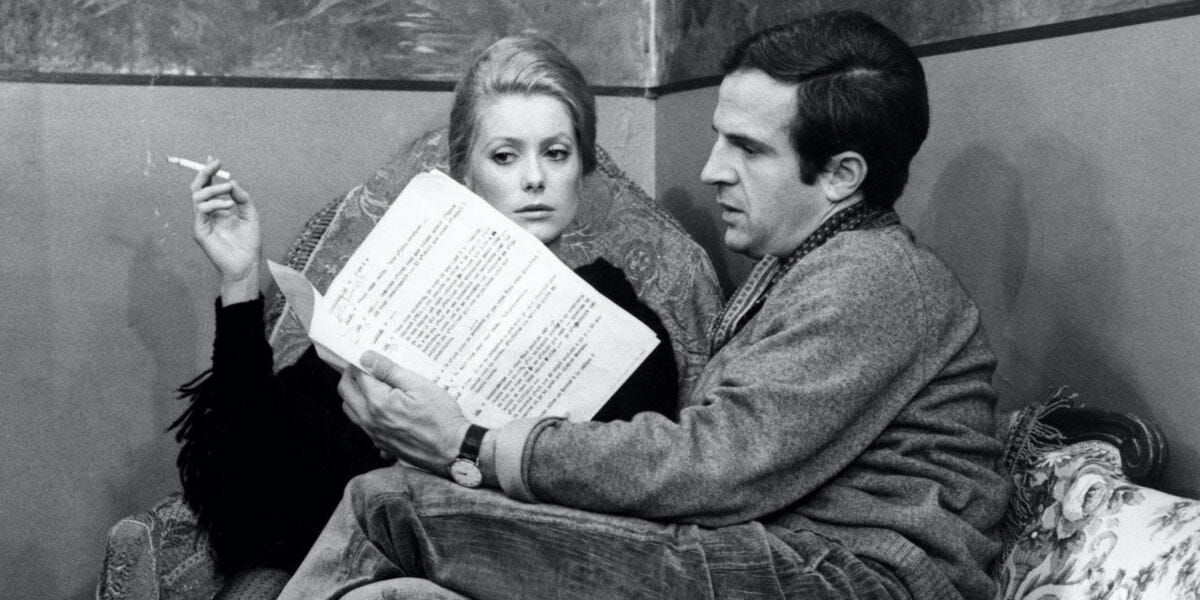

(Above: Deneuve and Truffaut going over some pages of the script for La Sirène du Mississipi)

(Above: Welty and Hains during an interview for the Mississippi PBS station)

I write a lot about Frank in my first memoir Mississippi Sissy. I lived my last summer there in his front bedroom in his home his knowing friends called “Bleak House” because of its dilapidated grandeur based on its exterior, but once inside it was a set designer's dream of order and style and beauty for Frank also designed sets for New Stage Theatre in town where he and Miss Welty were active members. His house sat on a little hill right across from one of those cemeteries in my life, this one Jackson's lone Jewish one. It was in that house where I found Frank one Sunday night bludgeoned to death. A scandal played out in the media - "a homosexual murder" was the term used - and I agreed to allow my name as the "houseboy" to be used as a suspect in order to flush out the real culprit. I was about to leave Mississippi that August for New York and Juilliard’s Drama Division so I thought, “Why not” if it helped solve the case. I was so full of anger and sorrow, the two guiding principles in my life for so much of it. I am still working through them as a 67-year-old man who has let go of everything in my life to live as a pilgrim in the world yet still not only carry around that 19-year-old boy who found his mentor bludgeoned to death, but also the little boy who lost his parents back-to-back to a car accident and then cancer in 1963 and 1964, a kind of emotional violence that matched the very real violence that took Frank's life. Anger and sorrow were my drugs of choice long before meth which sent me into recovery a dozen years ago, and it was in the context of such anger and such sorrow with which I allowed my name to be bandied about in the press in order for the police to capture the real suspect who was on the run down in New Orleans, someone the police wanted to think he wasn't being looked for so he'd make a wrong move and be found. He was. I am alas still trying to find myself in the muck of such memories, I realized the other day standing staring at Truffaut’s grave and remembering Frank’s death.

In the midst of the murder scandal when his name was being muddied and mauled - much more than mine - Miss Welty had had enough and insisted on writing a column about him there in his old space on the arts pages of the Jackson Daily News. She called for a stop to what was going on and wrote a beautiful tribute to Frank. This is some of what else is written about him at the Mississippi Encyclopedia by Ted Ownby:

"An openly gay man, Hains negotiated the realities of gay life at a time and place that discouraged discussion of anything but heterosexual relationships. Hains praised Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and pushed audiences to recognize the lead character’s homosexual relationship even when the Hollywood version left the issue unclear. Hains also defended other works by Williams and wrote highly of works by Lillian Hellman and Kenneth Anger that addressed issues of homosexuality. He allowed readers of his column to consider the nature of his life—joking about living alone and never marrying, enjoying musical theater, and celebrating literature that addressed complex sexual issues—without ever explicitly discussing his own sexuality.

"To the horror of his readers and friends, including numerous writers, artists, and theater lovers, a drifter beat Hains to death in his Jackson home in 1975. His friend Eudora Welty wrote a column after his death, beginning, 'For all his years with us, Frank Hains wrote on the arts with perception and clarity, with wit and force of mind. And that mind was first-rate—informed, uncommonly quick and sensitive, keenly responsive. But Frank did more than write well on the arts. He cared. And he worked, worked, worked for their furtherance in this city and state. He was a doer and a maker and a giver. Talented and versatile to a rare degree, he lived in the arts, in their thick.'"

Sometimes it dawns on me the deep influence that gentle, empathetic, talented, generous Frank Hains had on me. It certainly did so unexpectedly the other day at Truffaut’s gravesite. I moved to New York to become an actor - Frank even gave me the money to fly to New York to audition for Juilliard - but I became a writer. I wrote about entertainment and culture for close to 15 years at Vanity Fair. I continue to do so. I have even, following in his footsteps, become a columnist now here on Substack. In so many ways, I became Frank Hains. I allowed Frank - he died at the age of 49 - to continue on within me. I live in the arts, in their thick.

I am so grateful this deeply kind man was in my life - even his insisting I see Truffaut twice in one week when I was 19 was an act of kindness. He saw me as a southern sissy with a spine because he was one, too. I will never let this dear, talented man and his kindness be forgotten. I will always pay it forward. I remembered him profoundly the other day standing in Montmartre Cemetery when I happened upon the reflections there at Truffaut’s grave, which was not the only place this flâneur ended up where I was going all along. I also ended up at Frank’s memory, his presence in the natural order of my life. I say his name this morning: Frank Hains. I spell it. He is part of the language of me.

I had a kind of a mentor like Frank: My 7th grade English teacher in Leavenworth, Kansas, Mr. Lockhart. He was a gay man who lived alone in a little converted garage behind an old woman's house downtown. Although at age 12-13, I didn't know he was gay...I didn't know what gay was...but it didn't take me long after I got a little older to come to that conclusion. Lockhart taught me everything I know about writing the English language. From day 1 in the 7th grade he gave us an assignment every day: after learning to diagram the sentence we studied that day -- he began with simple declarative, of course -- we had to write 20 sentences of that kind and turn them in the next morning. Twenty sentences. Every day. For an entire year. That alone pretty much turned me into a writer, the daily-ness of it. During the first 10 minutes of the next class, he would return our pages from the day before yesterday, after he had graded them overnight, marked with a grade A through F. The grades counted. We were allowed to examine the pages for a moment, and if we thought we deserved a better grade because he had marked one or more of our sentences wrongly, we were allowed to stand up and defend the sentence. There was a hitch. If you were right, you got an automatic A. If you we incorrect - again - you got an F. Lockhart would reach into a side drawer of his desk and withdraw one of those tiny gym towels, wad it up, and throw it, hitting you in the chest. He never missed. And he would cry out, "The crying towel for you, Mr. Truscott," in a voice he allowed to be as close to a "gay voice" as any he used. I, of course, got into it with him regularly, winning about as much as I lost. Later in the year, we would be writing the kind of sentences I write now -- properly constructed and punctuated, of course. We never had to learn those words like "subjunctive pluperfect" or whatever the hell they were. We just had to write the sentences properly.

Years later in the 70's when I was working for the Voice and for magazines, I was driving through Kansas going from one assignment to another, I saw Leavenworth on the map just north of Kansas City, and decided to stop by and thank Mr. Lockhart. It took me a whole day of detective work to find him in yet another converted garage behind another old woman's house. As I knocked on his screen door, I could dimly make out his figure reclining on a couch, stroking a cat that was lying on his stomach. "Who's there?' he called, hearing my knock. "It's Lucian Truscott, Mr. Lockhart. I've dome to thank you for making me a writer." Without even sitting up, he said, "Well, it's about goddamned time," and he invited me in. It turned out that he subscribed to the Voice and had read most of the magazine pieces I had written. He was sill teaching 7th grade English, albeit as a substitute teacher after 40 years teaching full time. The kids were just as impossible as we had been, he complained. I asked if I could take him to dinner, and he said as much as he would like to, he didn't think that was a very good idea. "With your appearance," he said of my long hair and leather fringed jacket and jeans, "if you're seen with me, people will think you're gay." I told him I didn't care. Being though of as gay because I was with Mr. Lockhart would be an honor. He started crying, just sobbing. I sat there and comforted him on the couch, my arm around his shoulders, as his cat walked back and forth at our feet, rubbing its long fur against the two of us. I quite literally owe my life to Mr. Lockhart.

Kevin...once again your words astonish me. “I say his name this morning: Frank Hains. I spell it. He is part of the language of me.”

Perfection.