RUBRICS: IN MEMORIAM

STARS IN BLACK TURTLENECKS, SOME JOY, BEFORE GOOGLE in memory of photographer Marcus Leatherdale

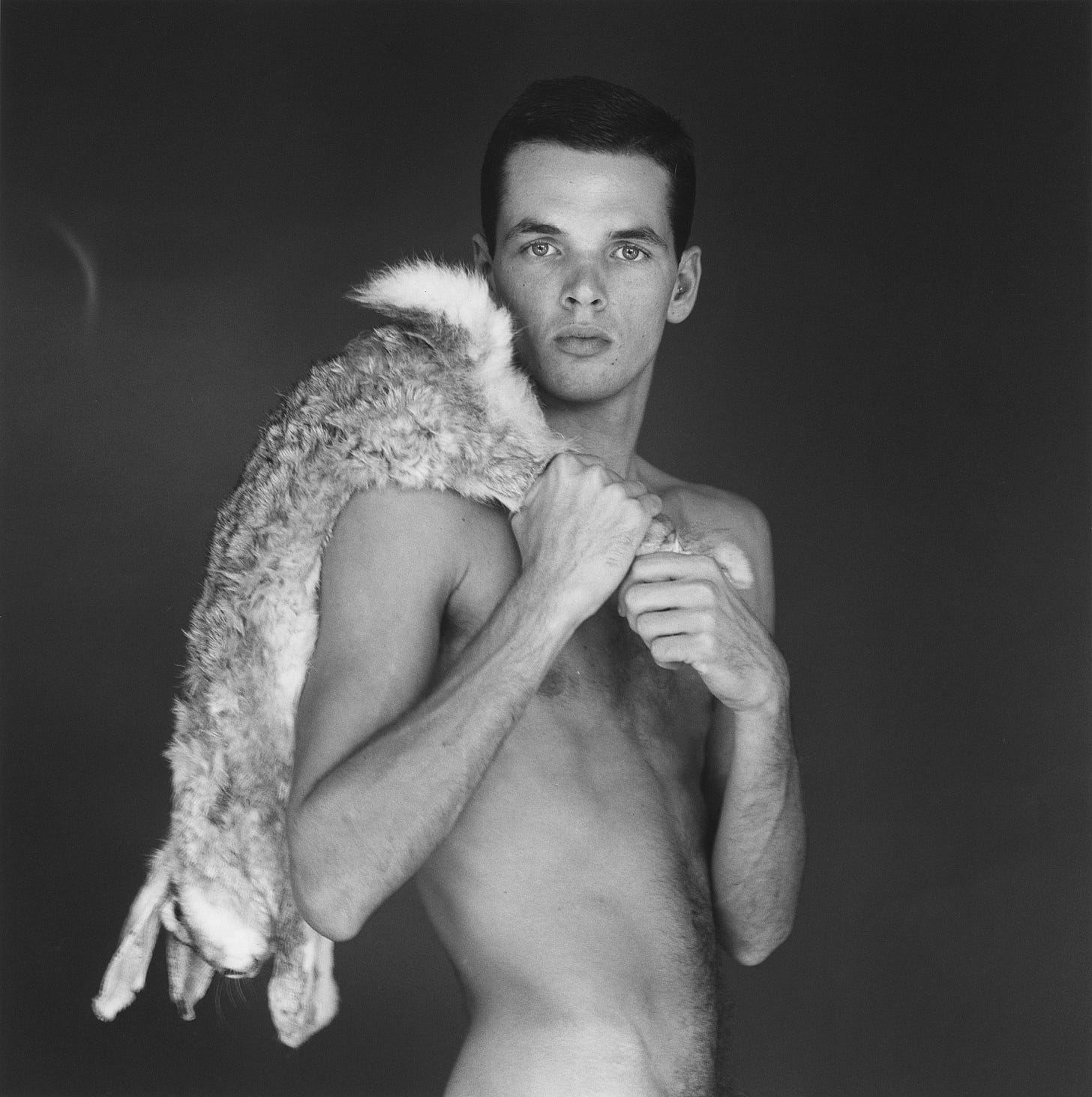

(Above: Marcus Leatherdale photographed by Robert Mapplethorpe. 1978)

Photographer Marcus Leatherdale died by suicide last week. I had lunch with him last June in Hudson along with a mutual friend and his son with whom he was staying on a visit from his home in Portugal. I seem to remember his being a vegetarian during that lunch. I could be wrong. Even if he had not been, I am not sure how he would feel about this dead hare utilized as a prop in this Mapplethorpe photo of him which, I presume, Robert was using for his own reasons because it is so purposefully a part of the frame, an allusion to still life paintings perhaps in the 18th and 19th centuries when dead hares held a place of honor so often in the foreground and hunts were celebrated. Early Flemish and English paintings are full of them. The more I looked at this photograph this morning, it became a portrait of a dead hare with a naked boy as its prop. There is something both profoundly sad and disturbing and alluring all at once about this portrait of death slung over a lad’s shoulder in that luscious shrug that youth itself is. Suicide itself is purposeful. Disturbing. And in some alluring way for those who decide that it is a rational solution, a luscious last shrug at life. For those of us who are left to make sense of it, it is alas profoundly sad. I was profoundly sad when I heard of Marcus’s death by his own hand, a hand that had held a camera and created such beautiful work. And yet what does photography do finally but frame a life in stillness. He stilled his own. He framed it.

I was also reminded of Wie man dem toten Hasen die Bilder erklärt, a performance piece by Joseph Beuys which he conjured in 1965. The title’s translation is How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare. It was performed by Beuys at the Galerie Schmela in Düsseldorf. He locked the doors to the gallery from the inside and viewers could only see him through some windows as he walked about the gallery with honey poured over his head - which was also crowned with gold leaf - and whispered to the dead hare he cradled in his arms as he roamed from painting to painting in the gallery and explained the art to the animal. It was in some way a ritualization of silence - which is what suicide is finally. Bueys explained the enactment: “For me the hare is a symbol of incarnation, which the hare really enacts- something a human can only do in imagination. It burrows, building itself a home in the earth. Thus it incarnates itself in the earth: that alone is important. So it seems to me. Honey on my head of course has to do with thought. While humans do not have the ability to produce honey, they do have the ability to think, to produce ideas. Therefore the stale and morbid nature of thought is once again made living. Honey is an undoubtedly living substance- human thoughts can also become alive. On the other hand intellectualizing can be deadly to thought: one can talk one's mind to death in politics or in academia.”

Trying to explain Marcus Leatherdale’s suicide - or anyone’s - is like trying to explain art to a dead hare. What is heard is silence. Silence is the explanation.

(Above: At lunch in Hudson, New York, at Le Gamin last June with Marcus Leatherdale, Pieter Estersohn, and his son Elio Estersohn.)

In his memory, here are some of his photographs under our RUBRICS today.

(TO SEE THE CURATED GALLERY OF MARCUS LEATHERDALE PHOTOS ETC., SUBSCRIBE FOR $5 A MONTH OR $50 A YEAR. THANKS.)