SOME JOY: Josephine Baker

I have always loved this photo of Josephine Baker sharing a laugh with Eartha Kitt. Yesterday I finished up my column about finding order and decency within the indecency and disorder being unleashed by Trump and his regime with an ode to baking and the contemplative meditative meaning I can find in being a bit of a baker myself. So as a through-line today I thought I’d highlight some other kinds of Bakers. First up: Josephine.

In another example of my everything-connects life, I was quite friendly with one of her adopted rainbow tribe of children, Jean-Claude Baker, who owned the Chez Josephine restaurant on West 42nd Street in New York City. I think she was really only his official guardian after meeting him when he was 14 and a bellhop at Hotel Scribe in Paris. He was a dear man who was a little fumblingly fussy in his failed attempts not to be so fancy - not really - even though he was never quite fancy enough for his own ideas about himself perhaps. There was always a noticeable ennui that seeped through his caring resolve - his arch charm - to render a public display of … well … joy for the paying customer. Perhaps he adopted that from his adoptive mother. I had a soft spot in my heart for him and his death by suicide in 2015 at his home in East Hampton both shocked and saddened me.

In my research, I found this essay about Josephine by Melania Zeck from the Oxford University Press’s website. It is from 2014.

JOSEPHINE BAKER, THE MOST SENSATIONAL WOMAN ANYBODY EVER SAW

Perhaps Ernest Hemingway knew best when he claimed that Josephine Baker was the “most sensational woman anybody ever saw. Or ever will.” Indeed, Josephine Baker was sensational–as an African American coming of age in the 1920s, she took Paris by storm in La Revue Nègre and relished a career in entertainment that spanned fifty years. Baker’s fans on both sides of the Atlantic still celebrate her legendary charisma.

Born in St. Louis as Freda Josephine McDonald, Josephine’s early years were marked by financial struggles and racial conflict. She managed to escape what promised to be an otherwise dismal future with her innate ability to charm others through singing and dancing. Having taken the surname of her second husband (she had already been married once before at the age of thirteen), Josephine Baker left for New York City. She started out as a chorus girl in Shuffle Along, a vaudeville revue by Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake, and subsequently starred in Blake’s Chocolate Dandies. Later, she performed at New York’s renowned Plantation Club where she was “discovered” by producer Caroline Dudley and asked to be in La Revue Nègre. As part of Dudley’s assemblage of performers, Baker traveled to Paris in 1925, where she received rave reviews for her opening night performance at Théâtre des Champs Elysées in Paris. Shortly thereafter, she appeared on stage at the Folies-Bergère wearing only a “skirt” of bananas, a costume for which she became famous and one which left an indelible impression on the audience. After this, she often danced scantily clad, exuding a kind of exoticism that captivated her Parisian public.

Successful live performances led to her foray into film, beginning in 1927 with La Sirène des Tropiques. By 1930, she had dabbled in a career as a singer, having recorded for both Odeon and Columbia Records. Her Columbia recordings included songs such as “J’ai deux amours,” which she would perform at the Casino de Paris, one of the city’s great music halls. The Casino’s impresario, Henri Varna, not only showcased Baker’s talents, but he insisted that she act with the pizzazz and mystique of a superstar. To enhance her image, Baker was given a pet leopard named Chiquita, adorned with a diamond studded collar. The pair delighted (and occasionally shocked) the French public.

In the mid-1930s, she starred in two films, including Zouzou (1934), Princess Tam Tam (1935), neither of which was made readily available to the American public for another fifty-plus years. She also appeared in Moulin Rouge (1939), Fausse Alerte (1945), An Jedem Finger Zehn (1954), and Carosello Del Varietà(1955), but, as she also realized when doing studio recordings, she was only truly in her element on the stage.

After completing Princess Tam Tam, she returned to New York to appear in the Ziegfeld Follies, which featured choreography by George Balanchine, music by Vernon Duke, lyrics by Ira Gershwin, and notable performers including Bob Hope. In spite of the Follies’ display of talent, its appearance in New York was subjected to intensely vitriolic reviews. Some of the reviews attacked Baker specifically, by mapping current racial stereotypes and crippling expectations onto her and her performance–expectations which had not affected her career in France in such an irrevocably stark manner.

Although Baker was hurt by the Follies’ flop and the discrimination she faced in her home country, she chose to remain in the United States for the time being. In 1936, she announced her plans to open a night club on East 54th Street called Chez Josephine Baker. Within a year America’s racist climes became too much to bear and Baker returned to France, but France was no longer the utopian escape it once had been. Initial tensions with Germany and the subsequent German occupation ultimately made it very difficult for African-American entertainers to earn a living in France, despite the fact that they had been thriving just a decade earlier.

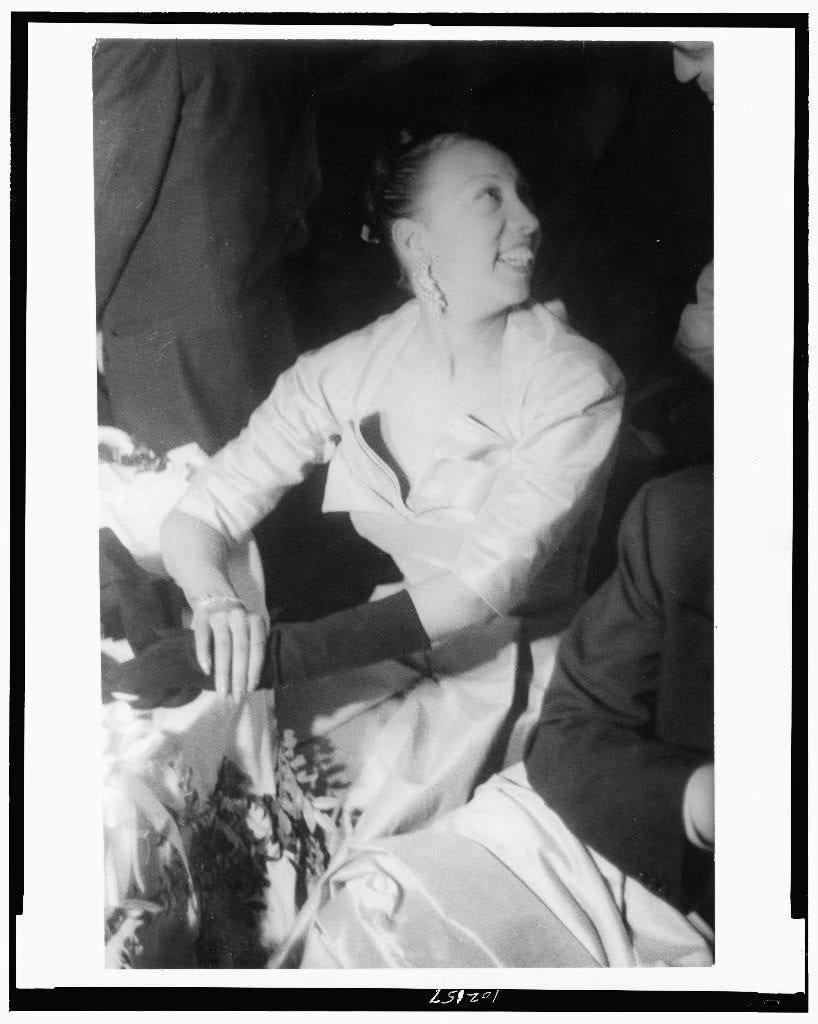

(Above: Baker photographed in 1951 by Carl Van Vechten which was atypical for him since it is a candid photo outside those posed in his West 55th Street studio within his apartment where he and his white gaze resided.)

Baker, who had married a French Jew, Jean Lion, in 1937, soon became involved in the Resistance, eventually working out of Casablanca as an air auxiliary lieutenant. She received the Croix de Guerre in recognition for her services in the Resistance. Those services included carrying classified information, written in invisible ink on her sheet music, to Portugal for transmission to England.

During World War II, she performed for American and British troops and war workers. These appearances put to rest all rumors circulating in the press that she had died, rumors prompted by the fact that she suffered a series of illnesses in the 1940s.

She reemerged in the 1950s as a staunch supporter and champion of human and civil rights. In 1951, she cancelled an appearance at the NAACP meeting in Atlanta because she, as an African American, was refused lodging. In 1959, she returned to the stage to raise funds for the International League Against Racism and Anti-Semitism (Ligue Internationale Contre le Racisme et l’Antisémitisme–LICRA).

Her most demonstrative gesture was to come. Beginning in 1953, Baker adopted the first of twelve children representing different races and ethnicities. She called her brood the “Rainbow Tribe,” and they are featured in Matthew Pratt Guterl’s book Josephine Baker and the Rainbow Tribe (Harvard University Press, 2014). They lived in a fifteenth-century castle, “Les Milandes,” which Baker purchased in 1947 but relinquished under extreme financial duress in 1968. Fortunately, her friend and supporter, Princess Grace, offered Baker and her tribe a home in Monaco.

As she aged, Baker found it increasingly challenging to maintain her career on the stage, but she persevered. In fact, on 8 April 1975, she gave a triumphant performance at the Bobino Theatre in Paris, which seemed to foreshadow prosperous days to come. That was not to be.

Four days later, on 12 April 1975, Baker went to sleep and never woke up. Thousands of adoring fans paid their respects, and nearly 2,000 mourners, led by Princess Grace, attended funeral services in Monaco, where Baker was buried.

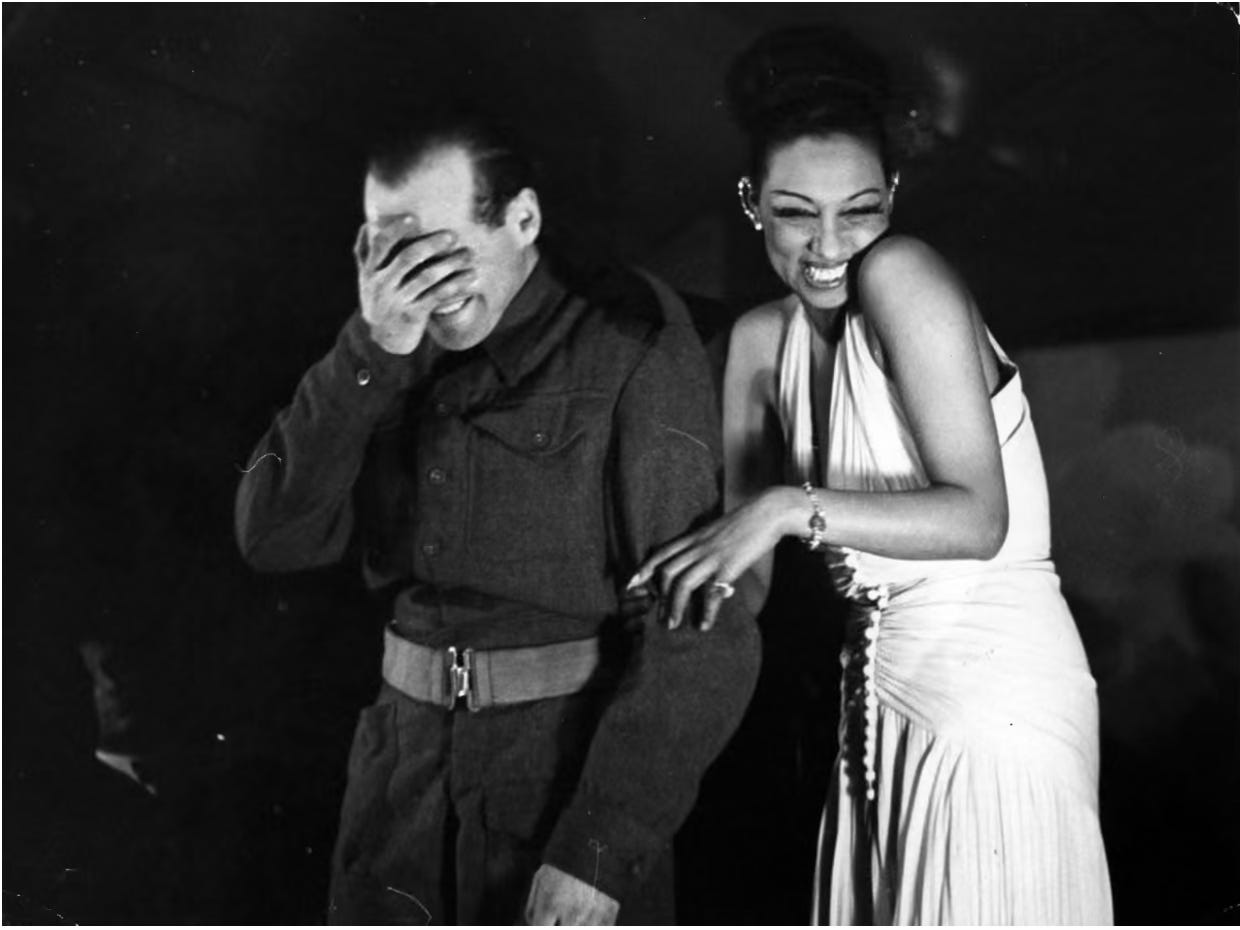

(Above: Baker entertains the troops at a London victory party in 1945. Photograph by Jack Esten/Getty Images)

(Above: Baker introducing Princess Grace and Prince Rainier III to some of her rainbow tribe of adopted children.)

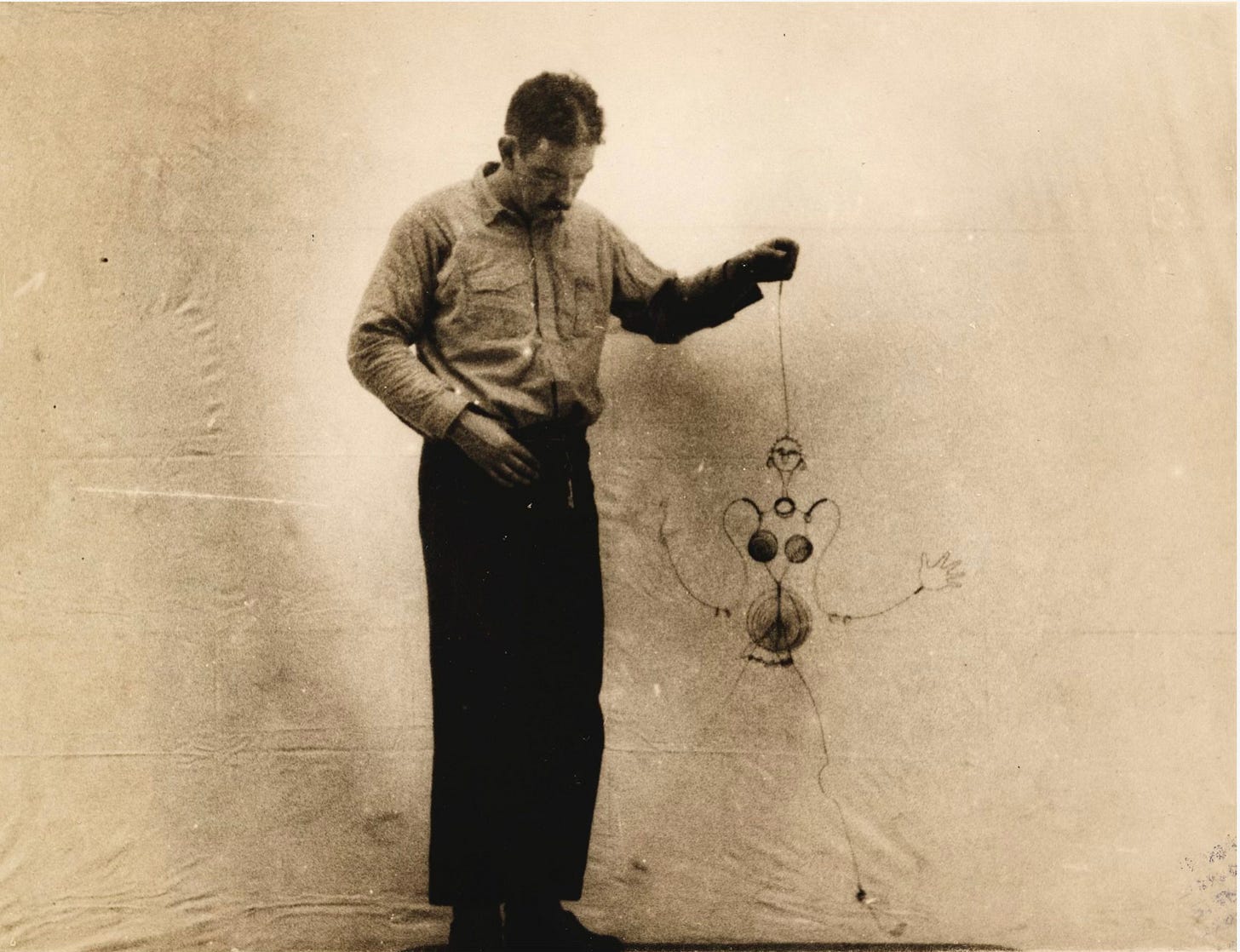

The above photo is of Alexander Calder holding Josephine Baker IV (c. 1928) during the filming of a Pathé newsreel in 1929.

The third iteration of the work is in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. This is the entry on its website where the work is displayed:

“‘I think best in wire,’ Calder once commented. The artist bent, pinched, and twisted strands of wire to fashion this tribute to Josephine Baker, one of the most celebrated performers of her day. For Calder, wire’s appeal was that it \moves of its own volition’ and ‘goes off into wild scrolls and tight tendrils’—a description that suits this portrait particularly well.

“But, while Josephine Baker III was innovative in its formal qualities, the exaggerated features of Calder’s depiction were in keeping with harmful caricatures of Black people in popular entertainment. Though Calder eventually dedicated himself entirely to abstract art, this figurative work—likely one of his first in wire—was a critical touchpoint for his lifelong interest in motion and shadow.”

####

The objectification of Baker in the Calder photo made me rather uncomfortable and even rather riled up in the way it is tethered as if chained to that objectification; there is both adoration and enslavement manifested there in not only Calder’s twisted artistic imagining of her but also his giant white male presence holding the tethering device. This is more than a white gaze. It is the white grasp of ownership if not of the body itself then the ways that such a body will be perceived. MoMA’s entry stated some of this in its own more academic way. The white grasp has continued this week as Trump and corporations have designated diversity as dangerous not only to the white grasp and gaze but also to the white entitlement of power. Such grasping, such entitlement, such manifested ownership is why Baker sought her refuge in Paris when she was 19 years old.

In my research, I additionally discovered that Henry Louis Gates when he was 22 was assigned by Time magazine to interview Baker along with James Baldwin about their being Black expats from America living abroad in 1973 a decade after the Civil Rights era. But when he turned in the story Time rejected the piece and told him that Baker and Baldwin were, according the editors assigned to his work, “now passé.” I have tried to access the interview which Gates published in the Summer 1985 issue of the Southern Review and which is buried beneath internet layers in other places but I just couldn’t pry it open. It will become my new white whale reconfigured as a Black one as I attempt to find it in the coming weeks. Maybe some of you will be able to do so where I failed. It might be a part of this anthology of conversations with Baldwin published by the University of Mississippi Press. (Yet again everything connects for this Mississippi sissy.). I did find an interesting essay by Gates that focused on Baldwins’s participation in the interview that was published in The New Republic. And a stirring essay at Literary Hub by Harmony Holiday in which she writes of Baker’s part in the conversation:

“We can sense that Josephine Baker is critiquing her white audiences in France, not pandering to them, by the way she discusses them in private. When she takes to the stage eyes splayed in a pretend bulge, ass kissing a skirted bunch of bananas barely covering it, she’s showing whites their callow understanding of Blackness, laughing at them. She uses them to abdicate that image by serving it back to them, their ridiculous Black fantasies. When they respond with rapture and become obsessed with tanning on the Riviera, she has succeeded—they know nothing about her but their burnt cafe olé skin. So that when she tells Gates the French got sick trying to get tan like Josephine Baker she’s ours again, not a legendary doll whites imitate but a woman we relate to who tricked them into admitting they wished they were Black. When she tells Gates and Jimmy that the US would not allow her back in the country until Kennedy became president, we realize how afraid white Americans are of their desire to be Black like Josephine Baker, afraid enough to try and pretend she didn’t exist, or to criminalize her existence, or to position her as some kind of ridiculous clown muse. Jimmy and Josephine share this lens into each other because they are both keen to what their every mannerism does to the white world, the way they’ve hypnotized their white fans with natural Black beauty and candor.”

There was maybe some hard-earned joy in that. I hope so.

Baldwin perhaps caught some of it in the play, The Welcome Table, he based on his and Baker’s conversation with Gates and on which he was working at this death. There are four known copies of it. One owned by Houghton Library, Harvard’s repository for rare books and manuscripts. Another can be found at the New York Public Library’s Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture. A third is reportedly in the collection of Walter Dallas, a Washington, D.C., theatre director. And the fourth is owned by Gates himself. He, in fact, titled a chapter in his book, Exile and Creativity, about his meeting with Baldwin and Baker “The Welcome Table.” I was able to find its opening paragraphs. Gates writes:

“Take one young, eager, Black American journalist-that was me. One aging actress-singer/star-that was Josephine Baker. And one luminary of black letters-James Baldwin. I was twenty-two, a London-based correspondent for Time magazine, and I felt like a mortal invited to dine at his personal Mount Olympus.

“My story, for which the magazine had sent me to France, was on ‘The Black Expatriate.’ One of my principal subjects was Baldwin. Another was Josephine Baker who, being a scenarist to her very heart, put a condition on her meeting with me. I was to arrange her reunion with Baldwin, whom she hadn't seen since leaving France many years before to live in Monte Carlo.

“Well into her sixties in 1973, Josephine Baker still had a lean dancer's body. One expected that. She was planning a return to the stage, after all. What was most surprising was her skin, smooth and soft as a child's. The French had called her ‘cafe-au-lait,’ but that says nothing of the translucency or the delicate shading of her face. Her makeup was limited to those kohl-rimmed eyes, elaborately lined and lashed, as if for the stage. She flirted continually with those eyes, telling her stories with almost as many facial expressions as words.

“I do not know what she made of me, with my gold-rimmed cool-blue shades and my bodacious Afro, but I was received like a dignitary of a foreign land who might just be a long-lost son. And so we set off, in my rented Ford, bearing precious cargo from Monte Carlo to Saint Paul de Vence, Provence, chez Baldwin. In case I was in any danger of forgetting that a living legend was my passenger, her fans mobbed our car at regular intervals. Invariably, she responded with elaborate grace, playing partly the star who expects to be adored, partly the aging performer who is simply grateful to be recognized.”

I am grateful to recognize her this weekend.

France institutionalized its own recognition by giving her a ceremonial burial in its Panthéon of national heroes in 2021. From Roger Cohen’s New York Times report:

“Josephine Baker, born in Missouri and beloved of France, whose life spanned French music-hall stardom and American civil rights activism, on Tuesday became the first Black woman to be inducted into the Panthéon, the nation’s hallowed tomb of heroes.

“On a gray afternoon, 46 years after her death in Paris, soldiers from the Republican Guard bore a flag-draped coffin up the red-carpeted stairs of the Panthéon, where Ms. Baker joined 75 men and five women, including the author Émile Zola, the scientist Marie Curie, and the resistance hero Jean Moulin.

“The coffin carried soil from the United States, France and Monaco — places that shaped Ms. Baker’s life. Her body, at the request of the family, will stay in Monaco.”

[To view and read the remaining RUBRICS this weekend, please consider joining our paid subscriber community for only $5 a month or $50 a year. Thanks.]