SATURDAY RUBRICS: 12/7/24

“You must go on. I can't go on. I'll go on.” ― Samuel Beckett, "The Unnamable"

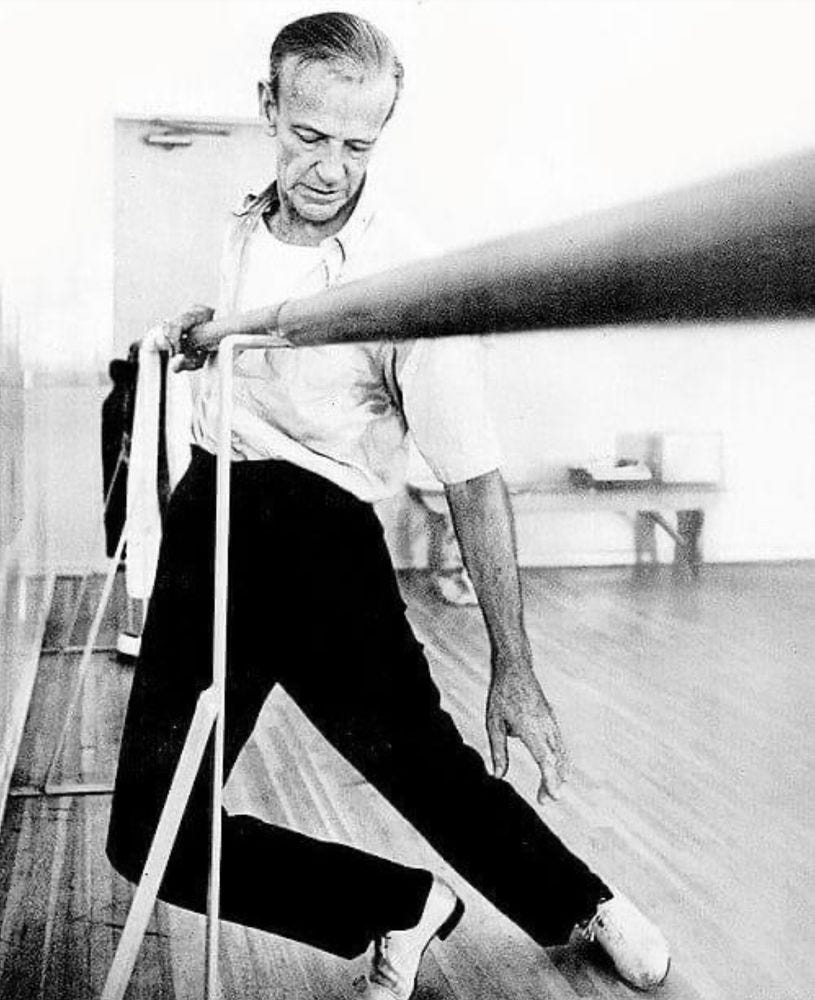

BEFORE GOOGLE: Fred Astaire still at the barre at 66

Fred Astaire was born in the 19th Century. He died at the age of 88 in 1987. In 1979, right before he was turning 80, Aljean Harmetz visited him for The New York Times. She wrote:

On Thursday, Fred Astaire will be 80 years old. Although he will still “occasionally get up and move around with some music I hear on television,” he has not really danced for almost eight years.

“I don't want to be the oldest performer in captivity. I don't know why anybody should expect a dancer to go on forever. No athletic career goes on forever.” His tone is a mixture of irritation at the insult of being 80 and exasperation at a world that chooses to make a fuss about such things.

“I don't want to be a professional octogenarian. I feel very much the same as I have always felt, but I couldn't attempt to do the physical exertion now without being a damn fool. At this age, it's ridiculous. I don't want to look like a little old man dancing out there.”

Through 35 years and 30 motion pictures, he looked like what he was — an inimitable artist whom George Balanchine has called “the greatest dancer in the world.” He was absolute elegance moving in intricate and surprising ways, with more wit in his feet than most people have in their heads.

None of the elegance has been lost to age. With his paisley handkerchief, his matching paisley cravat pinned to the open throat of his yellow shirt, and his yellow cardigan beneath a gray tweed jacket, he looks spiffy. His 5‐foot 9‐inch frame is slim and natty, with no hint of a pot belly under the belt buckle that matches the buckles on his suede shoes.

He got on so many best‐dressed lists, he says, “because I wore a dress suit in so many movies.” Yet, he added, “ hated dress suits. I had to change the collar five times an hour because it wilted like a piece of lettuce. Now I only have to wear one at the White House.” He made his last visit to the White House in December 1978, to receive medal. He became — along with Marian Anderson, George Balanchine, Richard Rodgers and Arthur Rubinstein — a recipient of the first annual Kennedy Center Honors in the Performing Arts. But he is wrong about all those best‐dressed lists. No matter what he was wearing, the stylishness with which he wore it would have put him on.

He sits in the massive library of the house he carved out of a Beverly Hills canyon in 1960. The house is a bowl scooped out of the hillside; three weeks ago coyotes killed a fawn in his rose garden. There are six Emmys crowded into a bookshelf on one side of the enormous room. They were won for the Fred Astaire television specials he did in the 1960's. Now he is more likely to watch television than perform on it. He has become addicted to “As the World Turns” and “The Guiding Light.” If he misses either of these soap operas, he will telephone his housekeeper to find out what happened.

But he is by no means retired. He wakes, as he always has, at 5 A.M. After working a few crossword puzzles, he is likely to spend half the morning writing songs. The task is more difficult since his partner, Tommy Wolf, died a few months ago. He appears occasionally on television, most notably last spring opposite Helen Hayes in “The Family Upside Down,” as an elderly housepainter trundled off to a convalescent home after he has a heart attack.

To please one of his six grandchildren, he even played a role in “Battlestar Galactica.” He turned down a role in “The Hurricane,” because he didn't want to spend three months in BoraBora, but he is in negotiation for a possible movie to be made in 1980. He did dance a little in “That's Entertainment, Part 2” in 1976. “Gene Kelly and. I were hosts in that movie. I told Gene we can't just stand around and talk or it will look like we have fallen arches and can't move anymore. It worked well but it was so very, very strenuous.”

He remembers his career as “all foreground.” It moves inside his head like a panorama without depth. “It's like it all happened at once,” he says. “It must be the same for football players, all the years blending into one big tackle and run. I was always planning or rehearsing or doing new numbers and there was nothing I didn't enjoy when I was doing it. Afterward, when I saw it on the screen and it didn't quite work, I was disappointed with the failure. ‘Finian's Rainbow’ was the biggest disappointment.”

The quiet life he lives now is little changed from the quiet life he has always led. He breakfasts on a single boiled egg, keeps his weight at a perpetual 134 pounds, is most often asleep by 10:30. His first and only wife died in 1959, after a marriage of 21 years. When he takes a young lady out, “she kindly drives,” he says, joking about his own distaste for driving. He has been forced to drive himself, however, “since my chauffeur died on me too.”

He considers moving to a ranch where he can keep his brood mares. Where the library is crammed with statues and plaques he has won for his dancing, the bar is covered with the bowls and cups such race horses as Triplicate and Don's Music have won for him. On the opposite wall are dozens of aging photographs — Noel Coward, Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, George Gershwin. He throws up his hands in a gesture of anger. “All those people gone!”

His own health has been remarkably good. Except for breaking his wrist when he fell off a skateboard two years ago, “nothing seems to go wrong with me,” he says. His mother died two summers ago at the age of 96, her wits intact.

There will be a small party at his house to mark his 80th birthday — his son, daughter and stepson and their families, and his older sister, Adele, his first dancing partner. Someone, he suspects, will bring him a cake. There is, in his voice, a warning that he will manage to keep this celebration private, as he managed to keep most of his life private.

A thin trace of exasperation still in his voice, he says: “All I can really say about it all is that I swear to you I have no regrets. I'm not trying to be modest, but I never thought of myself as No. 1. I'm cold‐blooded about dancing. wanted to make it good, then make it better. In the end, I didn't want to hear people say, ‘He doesn't get around like he used to. Why doesn't he quit?’ So thought, I'll quit when I feel like it, not when someone else tells me to.”

Although he has been unfailingly courteous, unwaveringly a gentleman, he is obviously relieved when a reporter is about to leave. He throws back his head and trots beside the car down the steep driveway toward the street below. Or, rather, he dances beside the car, elegantly, impeccably dances.

[TO VIEW AND READ THE REMAINING RUBRICS THIS WEEKEND, PLEASE CONSIDER JOINING OUR PAID SUBSCRIBER COMMUNITY FOR ONLY $5 A MONTH OR $50 A YEAR. THANKS.]