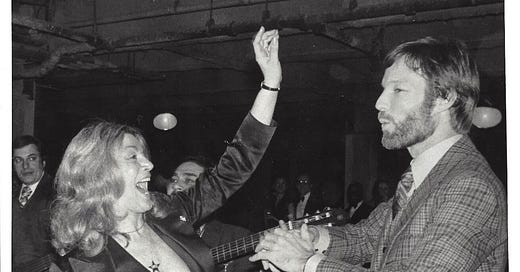

SOME JOY: Richard Chamberlain and Sylvia Miles at the opening night party for The Night of the Iguana in December of 1976 in which they starred as Shannon and Maxine at Broadway’s Circle in the Square Theatre. The limited-run production ended on February 20th, 1977.

Chamberlain was making his Broadway debut in the play after having played it at the Ahmanson Theatre in LA in an earlier iteration of the production. I saw him in the Broadway version. He was mesmerizing but I had always been mesmerized by him even before I understood being mesmerized by male beauty. He starred as the title character in the NBC drama Dr. Kildare and became a huge star in the early 1960s. The show aired from 1961 - 1966. I was ten when it finally went off the air and during its run I grew up a lot because my father died in 1963 and my mother died in 1964. I tried to get into Ben Casey after my mama’s death, another medical drama, that one starred Vince Edwards whom she preferred to Chamberlain and Dr. Kildared because she also preferred Vince’s swarthy look. I still assume that was because he looked more like my dead daddy which was something I wrote about in my first memoir, Mississippi Sissy. Chamberlain’s spiffed-up surfer boy sex appeal which was more polished than buffed, more carefully coiffed than tousled, roused something longing to be a bit more tousled in me that also longed for a kind of tussle for which I still had no language. There was also something oddly tamed about Chamberlain which he passed off as a rather timid aloofness but was really the result, I think, of his being in the closet. He came out of it as a gay man finally - and officially - in his 2003 memoir, Shattered Love. He was 68. He was 90 when he died from complications from a stroke last Saturday.

But we who are gay always knew he was one of us. Indeed, during the run of Iguana the word around the Broadway world - and I had it on good authority (the best actually) from my friend, Joe Hardy, who directed the production - was that he fell in love with the understudy for the roles of Pancho, Pedro, and Wolfgang. He was a young actor named Martin Rabbett. They were together until 2010 when they separated but, it was reported, that they had reunited recently and Rabbett was with Chamberlain at his death. Rabbett also released this statement: “Our beloved Richard is with the angels now. He is free and soaring to those loved ones before us. How blessed were we to have known such an amazing and loving soul. Love never dies. And our love is under his wings lifting him to his next great adventure.”

Here is Clive Barnes’s New York Times review of that Broadway production of The Night of the Iguana which ran in the paper’s December 17, 1976, edition:

We sometimes forget that Tennessee Williams is a comic writer. An ironic comic writer musing on the lonely tragedy of separateness, but musing with some humor. Most of his plays—not “The Glass Menagerie,” perhaps, and certainly not “Outcry"—might be justifiably termed “moral comedies.”

Just such a moral comedy is “The Night of the Iguana,” which was effectively revived last night at the uptown Circle in the Square. The play is, as so many plays are, concerned with a group of characters on the brink of discovery and change, It is set in a hotel in Mexico, in 1940. The hotel is run by the recently widowed Maxine, an amiable, blowzy woman, of no particular complexity. To this hotel comes the Rev. T. Lawrence Shannon, a disbarred Episcopalian priest. He is, as the playwright suggests, “a man of God on vacation,” a long vacation. He was disbarred from his ministry after one year for making sexual advances to a young girl in the vestry and blaspheming God from his pulpit. He is now a shabbily rumpled tour guide who looks like a refugee from Graham Greene.

Shannon has brought a brood of Texas ladies with him. Most of them he has left down the path to the hotel, in a bus. They are not going very far because Shannon has prudently immobilized the bus. He is having ttouble with his party. The chief troublemaker is Miss Judith Fellowes, a professional do‐gooder and busybody. At home she also teaches music, and it seems that her favorite student, a teen‐age nymphet called Charlotte, has just seduced Shannon, leaving him liable for charges of statutory rape back in Houston. Into this happy scene come the 97‐year‐old Jonathan Coffin, “the oldest livitig and practicing playwright,” and his spinster granddaughter, a woman of resource but no resources, Hannah Jelkes.

The party is made up. The play can begin. Very cleverly, Mr. Williams weaves his themes of comedy and pathos, of God and inevitability, of free will and bondage, all on this night of the Iguana. Why “The Night of the Iguana”? Two of Maxine's Mexican servants have caught an Iguana lizard, and have tied it up, intending to fatten it until it is big enough to eat. This creature, tied up in the dark, appeals to the playwright as a symbol of the human condition.

The play started as a short story, became a one‐act play for Spoleto, and was finally developed for Broadway, in more-or-less its present form. A little of this genesis is still evident—some of the intercrossing themes have a short story ring to them, such as the spinster's tale of her limited but unusual sexual experiences, and at times it does also seem that the play has been elongated in places. This does not matter, for the various disparate elements have all been combined with Mr. Williams's own casually romantic poetry.

The play emerges all of a piece, set in its steamy Mexican rain forest, with overheated emotions and quaintly effective symbols of man and his destiny. There is also the crackling, natural humor, the sheer fun of the piece, and, of course, its theatricality. Very few playwrights would have the courage and skill to give the play its present ending, and even fewer would give that ending a feeling not of defeat, but of resolution.

Joseph Hardy, the director, we have long known, is an expert at drawing new things out of old plays. He approaches revivals not as resuscitations, but as renewals, and this enables him to bring the kind of freshness to a production that he provides in this “Night of the Iguana.”

The scenery by H. R. Poindexter is perfect for the play, a vividly realistic reconstruction of a seedy yet beautiful Mexican hotel. It has the green luxuriance of the play to it, and together with Noel Taylor's evocative period costumes, it provides the author with just the living room he needs.

In this environment, Mr. Hardy and his cast work with a happy familiarity. Everything conspires to make one imagine a life outside the play, down the unseen hill, or behind the lush tropical foliage. The acting is bold rather than subtle, but Mr. Williams usually writes like that—his plays call for courageous strokes and only small, if vital, finesses.

Richard Chamberlain, making his Broadway debut as this burnt‐out case of broken‐down preacher, is excellent in his doubts, his strengths, his desperations. He looks defeated and yet gallant, a wronged, rather than damned, soul. Dorothy McGuire, tight, gentle, confident and yet inwardly nervous, makes a fine foil to him as the spinster, while Sylvia Miles, loping through the play with brash if quizzical sensuality, completes the odd sexual triangle. A fine word, too, for William Roerick's aging, even aged, poet, and Barbara Caruso's termagant of a music mistress. All in all, a great evening in the theater.

###

Here’s a clip from an episode of Dr. Kildare. I love that Jean Stapleton had a supporting role as one of the nurses. And although the opening is rather sexist in making its point about how dreamy Chamberlain is in the role it also proves that Netflix’s Adolescence wasn’t the first television show to incorporate a long tracking shot. This was over 50 years ago.

[TO READ AND VIEW THE REMAINING RUBRICS THIS WEEKEND, PLEASE CONSIDER JOINING OUR PAID SUBSCRIBER COMMUNITY FOR ONLY $5 A MONTH OR $50 A YEAR. THANKS.]