TANGIER NEWSLETTER: 9/20/24*

MUHAMMAD, MUHAMMAD, MUHAMMAD, & MUHAMMAD

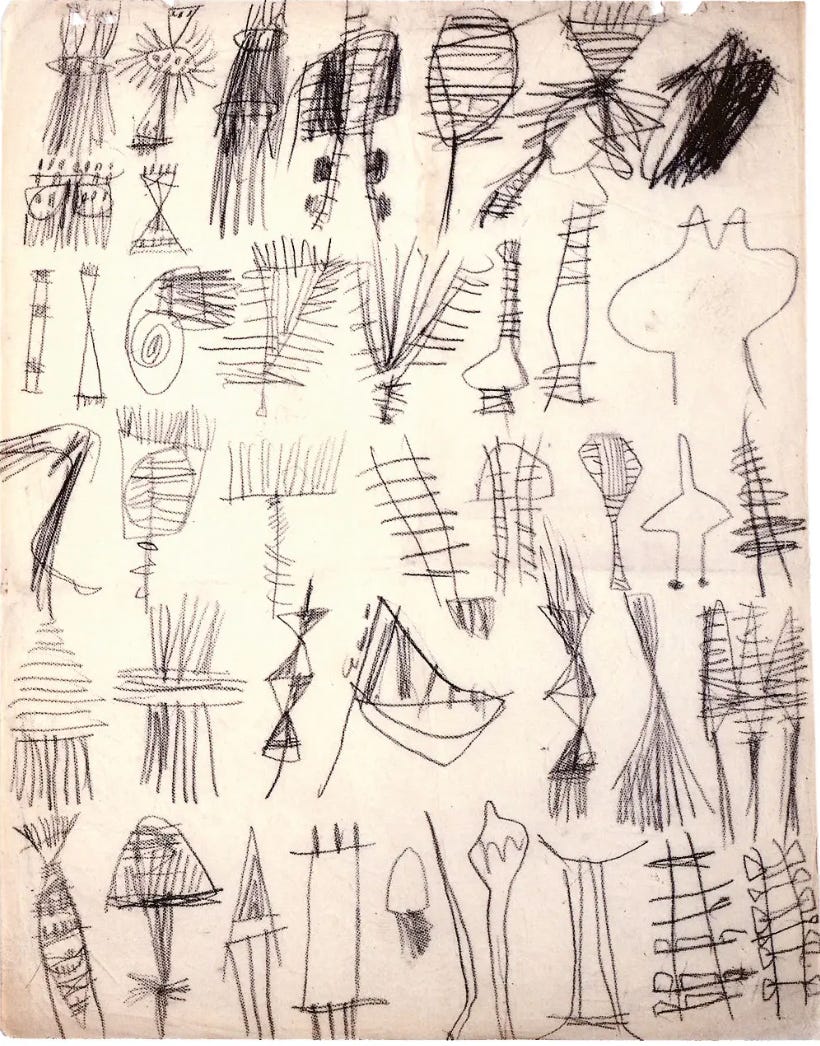

(Above: A page from one of Cy Twombly’s North African sketchbooks when he and Robert Rauschenberg were traveling together and staying in Tangier and its environs. “Untitled (North African Sketchbook),” 1953, private collection, N.Y., © Cy Twombly Foundation)

This is the week when The Prophet Muhammad’s birthday was celebrated in Morocco. It fell on Monday but both Monday and Tuesday served as a tandem national holiday here. I asked Anas, one of the young people who works at the Dar Gara hostel where I am staying for my three months in Tangier, if it is like our Thanksgiving in America and thus the holiday is used for family gatherings and big dinners. He said it is. I’m never quite sure if I am completely understood when I ask such questions but I do know that a sincere attempt is being made by both the person to whom I am speaking and by me for each of us to understand the other across a cultural divide. That itself seems like a kind of holiday - not one we celebrate in America but an extended one I instead am taking away from it right now that has become heightened during this election season back home, although “home” to me is now a peripatetic concept that I carry within me and is no longer a geographic one. It is spiritual, not spacial, its layout leaning into the liminal and away from the architectural. I don’t quite understand it yet as I am still in the nascent first years of this pilgrimage that is now my life, but even in the not-quite-understanding, a liminality of languages and landscapes, I am finding a deeper understanding of home in that lack of understanding and, moreover, my surprising comfort in not quite being able to do so. It is not uncertainty but instead (I am sure of it) a mysteriousness full of the welcome call of wonder. And there is a magnificence in how simple it finally all is as I fall into it - trust it - because I am realizing I am not seeking a greater truth on this pilgrimage. I leave that to religions to hash out in hallowed and horrible ways. I am trying to find a lesser one where such an itinerant life aligns and where an old monk-like man has no need for monasteries but only a room where a desk can be used to pour these decipherments of doubt into a few faithful paragraphs each day which serves for me as a form of prayer. I have always wanted to understand, to comprehend, to control the narrative, to expand my knowledge, to comment upon the flow of events with a knowing nod keenly attuned to the cynicism of others as I skirted my own. Now? I just want to notice. Pay witness. Record. Surrender to each sentence in such paragraphs that emerge along this columned way. It’s a different manner of existing within a narrative as a memoirist and writer with just enough credibility to be at times considered a journalist. In recovery, we learn about a deeper sort of surrender in our home groups where we go to share our narratives and read the stories of others from a book, quite a big one. Home. Groups. Surrender. Narratives. Stories. Sharing. Others. Somewhere in all that is where this pilgrimage began, and continues.

No. Wait. I think it actually began even further back when I became, like the Prophet Muhammad, an orphan. He lost both his parents by the age of 6. I lost both mine by the age of 8. I had not known that about Muhammad until, as part of this pilgrimage where I now find myself in Tangier, I took the time to read about him on the morning of his birthday. It had never occurred to me to do so before. I had no idea when I was a little orphaned sissy boy in Mississippi whose parentless state was where I really lived - my first liminal home - before I set out at 19 to move to New York City and attend the Juilliard School of Drama and then focused instead on my dream of not becoming a writer but admitting that I am one, nor when I set out later to walk the Camino de Santiago de Compostela the first time I actually called myself a pilgrim 15 years ago and was shocked when my epiphany on that path was my ceasing to be a Christian, which had been so culturally inculcated into me, and becoming instead a theist by pulling that “a” away from “atheist” to live in yet another liminal state, that space created there, a certainly mysterious one where the many I-don't-quite-understand gods exist, nor when I set out as well to seek some semblance of sobriety and first walked into a room to admit that I was a drug addict along with being a writer and a pilgrim and a theist and continued to seek the gods of my not-quite-understanding that they all would one day include Allah who would make an entrance this week on Muhammad’s birthday here in Tangier. Allah and All The Others, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot understand …

On Tuesday, I headed upstairs at the hostel for the daily breakfast prepared for all of us staying there. I often use the mornings when breakfast is being served on that upper terrace to suss out the newest guests since I have discovered that my staying there for three months is very much an outlier. Most guests are not only about 40 years younger than I, but also only there for a night or two with their backpacks as they are passing through Morocco on their own kinds of pilgrimages, ones toward their own adulthoods. I sat down next to one of them that morning over in a corner. “Where are you from?” I asked him.

“Palestine,” he said.

I asked if he and his family were okay.

“We live in the West Bank so it is better for us than for those in Gaza,” he said.

We continued to speak about our different lives. I told him that the only Middle Eastern country to which I had traveled was Qatar, which I pronounced as “Cutter.” He seemed to take notice of that and relaxed a bit more within the conversation. He told me that he had recently gotten his Masters Degree in Economic Development there. We spoke a bit more about politics and he told me that Arabs were more comfortable with the concept of authoritarianism and elites choosing their leaders than westerners are. I was surprised by the dispassion in his observation which led me to try to be dispassionate when discussing the upcoming presidential election in America. I told him I am grateful to have lived long enough to have seen a Black president and I hoped (I am sure of it) that I am now living long enough not only to see a female about to be elected president but a woman of color. “That astonishes me,” I said.

“To us Trump and Harris are no different,” he said. “Each will continue to arm Israel and with those weapons they will bombard us, murder us. We don’t see the difference in them from our perspective.”

“I understand that dilemma for you,” I told him as a small Palestinian flag that was attached to the awning over the terrace billowed a bit in the morning breeze and to which I pointed as I continued. “But if you were a gay man like me or a woman who has lost dominion over her own body or a Black person because of the racist Trump and his party, then you would see that there are differences.” I wasn’t sure how he would take my admitting that I am gay but he didn’t evince any disapproval of it. “Plus, if you were to immigrate to America then Trump would demonize you because you would be an immigrant of color.”

He turned the conversation back to Palestinian rights. “I think in your country it is generational,” he rightly observed. “I think people younger than you understand our struggle in Palestine.”

“I understand it, too,” I told him. “Netanyahu and Trump - not Harris - are joined at their political hips. I fear for a wider war there in your homeland because Netanyahu will think it aids Trump in his reelection since it most likely would send oil prices soaring. But you are correct. It is generational in America. I seek balance in lots of ways - even in looking at Palestine and Israel - although I recognize the imbalance of power because of America’s chosen role in it all.”

And then we turned to my own travel plans as I was heading to Chefchaouen for what I still thought would be a couple of days. He had just arrived from there the night before. “Some people tell me it’s too touristy,” I said, “but others say its beauty bests the tourism.”

“I like the mountains more than the sea,” he said. “So to me I liked it more than Tangier. I will always think of the sunset next to the mountain which I saw while standing at the top of the mosque there. I want to go back to see that again and not just in my mind. Make sure to try to do that yourself.”

“I am Kevin,” I said offering him my hand. “I will try to make things in my mind. I am making something right now by talking to you.”

“I am Muhammad,” he said. “It is a pleasure to meet you, Kevin. You, too, are in my mind.”

Muhammad then departed for the train station to head to Casablanca and then fly back home to Palestine. Anas was overseeing the breakfast on Tuesday and I asked him about how I was to catch a bus to Chefchaouen. I was worried that I had waited too late to book a ticket. Since it was the second day of the national holiday more people seemed to be traveling. He checked the bus schedules for me and, yes, discovered that there were not tickets until the evening. He then called his brother, also named Muhammad, to see if he would be willing to come drive me on his motorcycle to a parking lot full of vans that traveled to Tétouan, which is about 40 miles outside Tangier, where I could then catch another van in another parking lot filled with them to Chefchaouen. Muhammad, a sweetheart of a young man just like his brother, agreed to help me. When he later arrived at the hostel and was about to put my motorcycle helmet on my old bald monk-like head, I joked, “When I was coming to Tangier I had a fantasy that I would ride on the back of a motorcycle of a hot young man named Muhammad. And now I have manifested it.” Muhammad was already wearing his own helmet and all I could see were his eyes but I was relieved to see amusement in them. In some odd, ironically parallel way his hair and face were covered in the manner of Muslim women but with a masculine aplomb that was designed to ward off an accidental evil in an Evel way that made me think of yet another motorcyclist and writer and pilgrim, journalist Ted Simon, now 93, when he circumvented the globe from 1973 to 1977 on his Triumph Tiger and wrote about it in his memoir, Jupiter’s Travels.

When I climbed on the back of Muhammad’s motorcycle, I asked, “Is it okay if I touch you?” before getting the okay to place my hands on his hips as off we sped through the winding byways of the Medina before getting out on the real roads and roundabouts for about twenty minutes as we headed to the vans. Once there, much discussion ensued as a price was agreed upon - one that equaled $4 for each of the two legs of the journey’s over two hours. I had already given Muhammad bit over $4 for his twenty-minute motorcycle ride, one which both reawakened a sensuality within me as well as a feeling of real fear, a combination I hadn’t felt since I first harbored hormones that insisted on being identified as belonging to a homosexual, a term that sissy becomes when it seeps into puberty and floods your life with the yoke of yearning for what you are told you must not want.

Maybe it was having broken my shoulder in Paris over a year ago when I fell down those metro steps on the way to Orly Airport that made me feel so fearful on the back of that motorcycle as we wove through the Moroccan traffic on Tuesday morning, but I was suddenly queasily envisioning being back in an emergency room in a foreign country once we had an accident. The imagined queasiness was no match, however, for the real motion sickness that was to surface the rest of the afternoon in the back of those two vans that climbed the winding roads into the Moroccan mountains to get to Chefchaouen. I was so sick by the time we got there and had come much too close to throwing up several times in the bag I had emptied of my toiletries and put beneath my chin just in case it had to catch the vomit that kept trying to erupt. I much preferred to be back on that motorcycle with Muhammad remembering the hormones of my teenage years as we wove our way around Tangier. The memory of how that sensuality and fear wove themselves together as he and I wove our way through traffic was almost hormonal itself in its pull as I tried, remembering it as a remedy, to rid myself of the horrible nausea that still tugged at me as I trudged around that newest old Medina trying to find my latest hostel within all those blue walls with which Chefchaouen has branded itself.

Once I did find the hostel for which I had paid only $17 a night for a single room - a charming one called Vallparadis Pension Familiar in a corner of the Medina - I drank a lot of water and lay down trying to feel better. Once I did, I took a walk and decided after about two hours that once you’d seen one blue wall, you’d seen them all and that I had no need to be there for another full day. I decided that the people who warned me that the place was too touristy were right. Unlike my young Palestinian friend from earlier in the day, I preferred the sea to the mountains. I already missed Tangier and my routine there. The shops in Chefchaouen were lovely and far from junky but the whole place had a Disneyland feel to it and was set up for tourists to shop, to ogle, to buy.

And I am not a tourist.

I am a pilgrim.

I seek experiences not souvenirs.

I don’t even look for sights since my own sights are set in more internal, mindful ways. I don’t look at guide books but set out to just walk around each day knowing now that I am never lost because I always end up where I am supposed to be. And I knew that first evening in Chefchaouen that I was supposed to be back in Tangier. So I booked a seat on a big bus the next day. No more vans for me.

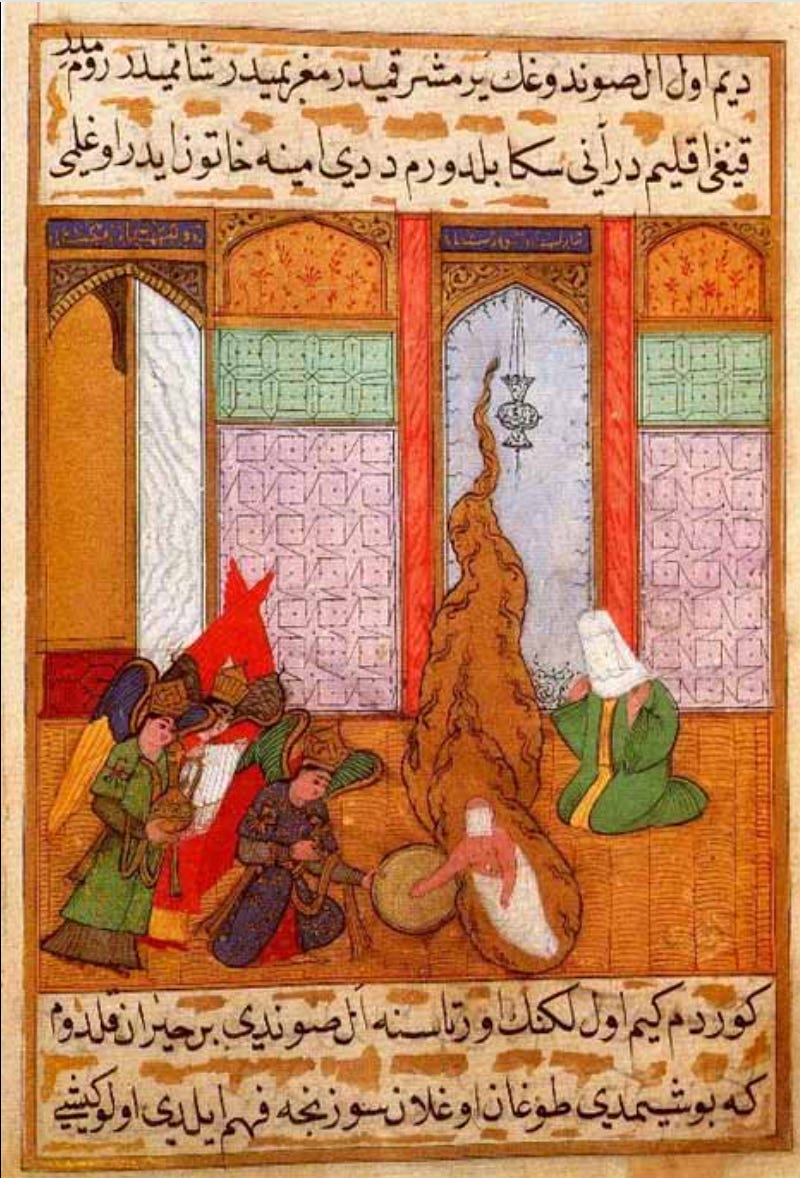

(Above: The birth of Muhammad in the 16th-century from the Siyer-i Nebi, an Ottoman epic about the life of The Prophet completed around 1388.)

That night I did have a lovely, inexpensive meal at Sinibad Restaurant which offers expansive views of the mountains and the city. Afterward I retrieved a large bottle of water from its refrigerated display case but only had a 200 dirham bill. The proprietor told me to go ahead and take it and come back to pay him once I had some change.

“But you don’t even know me,” I told him.

“That’s okay. I trust you. You will honor my trust,” he said.

“Well, I’ll come back for breakfast then,” I said. “You have my business.”

He put one hand on my shoulder and the other on his heart. “Not everything is about business, my friend,” he said.

I introduced myself and asked his name.

“I am Muhammad,” was the answer.

The next morning I did return to eat breakfast there. That afternoon I headed back here to Tangier a day early. The Muslim call to prayer in Chefchaouen - the adhan sung forth by the muezzin - had been more succinct and quieter than it is in Tangier which for the last almost three weeks has been difficult for me to get accustomed to with its echoing volume and length and a kind of choral insistence I had not noticed in Tunis before I arrived here nor for my short time within the blue mountain walls of Chefchaouen. But upon my return on Wednesday evening even its eruption within the corner of the Medina where it so loudly beckons - too loudly at times - with what I had been hearing as a terrible longing here in Tangier felt for the first time like a cacophony of comfort. A terrible longing? That description that just surfaced as I surrendered to that previous sentence in this prayerful paragraph where I am grappling with the deciphering of doubt could also be a description of how I felt - still feel - so yoked as I am to yearning that is not, I fear, sexual or hormonal or sensual, but deeply spiritual, a longing that led me to this pilgrimage. It has led me to Tangier. I sat listening to the muezzin’s own spiritual longing as the adhan adhered to it upon my early return to this Moroccan city by the sea this week that began with the celebration of Muhammad’s birth and longed myself not to understand it - is that terrible of me? - but instead to accept its mysteriousness full of what has become my home - not Tangier, not Chefchaouen, - but the welcome call of wonder.

Onward …

*The weekly NEWSLETTERS while I am in Tangier for the next 8 weeks will be titled TANGIER NEWSLETTER instead of WEDNESDAY NEWSLETTER and will be published on various days of each week. Thanks.

Enjoyed every word. Thank you.

Let peace find you.