TANGIER NEWSLETTER: 9/27/24

MOROCCO & MISSISSIPPI & ME: MELDING, DIFFERENCE, AND WHAT REALLY MATTERS

I.

“Are you, all right?” I was asked by one of the kind, cool Moroccan crew of young people who work at my hostel here in Tangier the other night when I was quieter than usual as I cooked myself some dinner in the outdoor kitchen next to where they congregate along the low-slung sofas on the upper terrace as they smoke their kif and their voices form a cacophony of Arabic sounds in a language so exotic to me, an openly gay American man who is old enough to be their grandfather - or جَدّ. - and who, in turn, is exotic to them. Or am I? Am I instead just a jester-like figure who both makes them, on cue, laugh in a performative manner with my remarks and openness - my own sincere attempts to befriend them a bit too performative too alas - but also at whom they laugh with more honesty when I, a cue ball who wants to believe the best about people even in my own ability to be witty across age and language barriers, am not understanding what they are saying in my presence. I assume I am liked but maybe I am because I can be derided to my face, just another American who has arrived in Tangier to take what I can from its culture to objectify it - and them - for my own use, as I am doing in this very column. Indeed, rolling out the term “exotic” to describe them already in this opening paragraph is both a compliment and diminution all at once even as I applied it to myself when seen by their eyes.

But can I ever really do that? See something from their eyes? Even myself.

My being in a culture so foreign to mine has certainly opened my own. And yet am I able to see differently because of it? Should that even be a goal if seeing the world that way diminishes me as a gay man whose own exotic nature is not nullified - which is impossible because it is so deeply indeed natural, innate - but still criminalized? I was quietly thinking the other night about my openness at being a gay man in their company and their culture as I continued to cook my eggs while not understanding anything being said around me and wondered if each time I talked about being a gay man or folded that into an understandable conversation, it was not a mission statement on my part - see? we are all just alike - because I am finally not at all just like them. Was what I thought of as a mission statement nothing instead but a criminal confession because the conversations - understood, not understood, misunderstood - are all taking place within a Medina embedded in a Moroccan kasbah where homosexuality (when acted upon) is against Article 489 of the Penal Code here which criminalizes "lewd or unnatural acts with an individual of the same sex.”? Oh, that’s just theoretical at this point, I’m told about such a law still on the books when I have brought it up. I want to respond, “You mean, like Islam and Christianity and Judaism?” But I know my place (and don’t really know this one enough) so I keep my own counsel, and cook more eggs.

The cacophony of their voices continued as the cacophony of such thoughts did alongside it. I took the eggs which I had scrambled that night with all their mixed ingredients from the pan - broccoli and spinach and Roquefort cheese - and wondered what the term would be for it? Spanish omelette? Frittata? I was, in my fretful state, even fretting over the correct terminology to comprehended an egg dish.

More low-slung laughter erupted around me from over on the terrace.

I told myself it wasn’t about me as I bit into a sliver of egg shell that had shamed the mixture of precise ingredients with its presence.

A call to prayer erupted.

“Are you okay?” I was asked again.

“I'm just contemplative tonight,” I said and we all fell silent as the call continued to fill the world around us, a roundelay echoing off the Medina walls of riads and dars, the darkest of corners, the highest of roofs, a balance trying to be found within the competing calls of muezzins from the many minarets that pierce the sky here, an architecture of acoustics that can make it aurally feel you are being religiously accosted while also being included in the soothing sonority of certitude that those who seek it find.

I have become certain of only this in Tangier: there is no silence like the silence that befalls us - infidels and believers, yes, alike - after the call to prayer suddenly, finally ceases.

The kif smoke curled within it and gave such silence a shape.

The young then filled it - suddenly, finally - with more of their laughter.

I longed to know the reason for it and join along but ate my eggs in another kind of silence, stilted, western, woeful, and thought of the dream I’d had the night before.

II.

“At some point in the night she had a dream. Or it was possible that she was partially awake, and was only remembering a dream? She was alone among the rocks on a dark coast beside the sea. The water surged upward and fell back languidly, and in the distance she heard surf breaking slowly on a sandy shore. It was comforting to be this close to the surface of the ocean and gaze at the intimate nocturnal details of its swelling and ebbing. And as she listened to the faraway breakers rolling up onto the beach, she became aware of another sound entwined with the intermittent crash of waves: a vast horizontal whisper across the bosom of the sea, carrying an ever-repeated phrase, regular as a lighthouse flashing: Dawn will be breaking soon. She listened a long time: again and again the scarcely audible words were whispered across the moving water. A great weight was being lifted slowly from her; little by little her happiness became more complete, and she awoke. Then she lay for a few minutes marveling at the dream, and once again fell asleep.”

- Paul Bowles, from Up Above the World

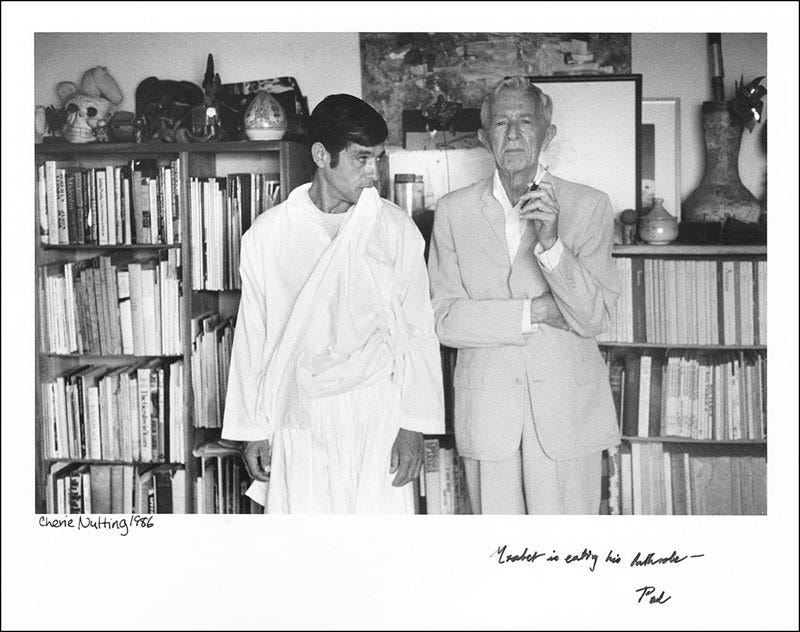

Above is a photo Bowles with his friend Mohammed Mrabet. “Bowles and Mrabet met in the early sixties, and they remained close until Bowles’s death four decades later in 1999,” wrote Lucy Scholes in an essay titled “The Storyteller of Tangier” in The Paris Review about Mrabet and his own work, especially his memoir, Look & Move On, which was translated by Bowles. “Mrabet worked for Bowles in various capacities: as a driver, a cook, general handyman, and sometime traveling companion. But theirs was much more intimate a relationship than that of employer and employee. They were friends—and it’s assumed, at one time or other, lovers, too—but most importantly, artistic collaborators. Throughout the sixties, Bowles increasingly turned his attention to translating. His wife, the novelist Jane Bowles, suffered a stroke in 1957, from which she never fully recovered. From then until her death in 1973, she was plagued by depression, impaired vision, seizures, and aphasia—health problems that also had a notable impact on her husband, depriving him of the ‘solitude and privacy’ that he needed to write.”

In another essay in The Paris Review titled “Paul Bowles in Tangier,” the novelist Frederic Tuten wrote of his time here teaching a summer writing course at the American School with Bowles and befriending him as best he could. Here are excepts from that essay:

On my second week in Tangier, Paul asked me to come to tea, and I kept finding excuses to postpone. I was afraid to visit him, thinking that no sooner would I walk through the door than the Moroccan police would burst in and arrest us all. He smoked kif all day long. In class he’d empty out a cigarette, finger in the kif, stick it in a holder, and smoke away, quietly, inhaling like an Austro-Hungarian aristocrat in a B movie.

I had been told that the police were rough with foreigners who used drugs, often entrapping them, especially the young who had come from Europe and America, and then putting them in prison where they were beyond the protection of their embassies. Bowles had never been arrested for smoking kif, but I was certain that were I with him chez lui, I’d be arrested and sent away to the most depraved prison and stay caged there forever. A fear that was, in part, thanks to Bowles himself, who, from the week I arrived in Tangier, fed me stories of dreadful police-doings.

Here’s one he relished: A middle-aged, conservative British couple on holiday motoring in the Maghreb mountains were stopped at a police barricade and their car searched. One of the policemen produced a package of kif, saying he had found it in their trunk. The couple denied ever possessing or knowing of such an item.

“Someone put it there,” the husband insisted, stopping short of an accusation against the two policemen and feeling assured that his word on the matter was sufficient. One of the policemen answered: “We are not happy. Make us happy.”

The couple was slow to get the point, but when they did they were irate—framed and extorted, they were, an outrage—and they told the policemen that they would be reported to the proper authorities. Husband and wife were arrested on the spot and hauled off to jail, where, finally, someone from the British consulate came dutifully to visit them.

It was a local matter; there was nothing really the consulate could do. But somewhere it was hinted that they could have avoided all that trouble at the onset by giving the policemen just a few pounds, but now they would have to get a Moroccan lawyer and go to court. Perhaps that lawyer could find a way to help them, in any event.

The lawyer suggested certain payments, emoluments to soothe the feelings of the arresting officers and to prepare for the goodwill of the presiding judge, and then, of course, there were his own fees. Having felt a bit of awful jail life and sensing that the outcome of the trial might not be based on their honesty and good word, they reluctantly let their lawyer take care of matters as he had suggested, and everyone who was involved, and some who were not, found their pockets heavier. Yet for all the soothing and the paving of kind feelings, the couple received a sentence of two years.

I was shocked. “Why were they sent to prison after they finally paid them off?”

“To teach them a lesson,” Paul said, smiling.

“How can you stay in such a scary place?” I asked.

“Who said I don’t like to be frightened?”

…

One day it was clear that if I again postponed visiting Bowles, I would never again be invited to tea and that our relationship would sour. Not that he would make me feel that directly—his indirectness was iceberg-scale—and, liking him, I didn’t want any ill feelings between us. I said that I wanted my girlfriend, Dooley, to meet him and that when she arrived in a week we’d set a date, and we’d both come for tea.

At the start of Ramadan, Dooley and I walked six flights up the newly washed Italian marble staircase to Bowles’s doorway. I was still out of breath when he opened the door.

“Why didn’t you take the elevator?” he asked. “Was it not working?”

“Yes,” I said, “but Dooley is frightened of elevators.”

“So was Jane,” he said, regarding my companion kindly. Paul’s longtime friend and protégé of many years, Mohammed Mrabet, was also there greeting us in faulty Spanish and crippled English.

Tired suitcases stacked high in the corridor stood as totems of Bowles’s travels. I fancied his beige living room, which gave off the glow of the desert at dusk. I felt immediately comfortable. Except for the Moroccan-style banquette, it was exactly like my friends’ Greenwich Village digs in the fifties: a living room with scatter rugs frayed at the edges, a low table for tea, a canvas sling chair. Everything orderly and clean but with the dusty patina of yesteryear. I can’t imagine it ever having changed since the day Paul moved in some forty years ago.

I had read about Mrabet and that he and Paul had been close for more than thirty years. Mrabet was a street urchin of fifteen when he met Paul. Illiterate, he was a natural-born storyteller, and Paul had tape-recorded his stories, transcribed and translated them, and aided in their publication. We settled down to drinking mint tea and exchanged pleasantries. Mrabet suddenly said, “Paul is my Papa!”

“Oh, that’s great,” I said.

“I am married. I have three or four children. I’m a no gay.”

“Oh,” Paul said laughing. “He chased Alfred Chester around the apartment threatening to kill him because he called him my sexy cowboy.”

“He was a big stupido,” Mrabet said. “Paul knows many stupidos. But you’re not one. You’ve never come to bother him.”

Paul laughed. “Because he never comes.”

While we were drinking tea, Mrabet opened a green cloth bag and took out a load of kif, and he and Paul set about to separate the seeds. They started to smoke as they worked. Mrabet offered Dooley some hash. She smoked a bit and seemed staggered. “I feel like I’ve gone through a wall,” she said.

“Do you have anything to drink other than tea?” I asked. I was hoping for a big glass of scotch.

“No. No alcohol,” Mrabet said. “Kif,” he said, with a big smile.

“I have an allergy to all drugs,” I said, “all except alcohol.”

Everyone laughed warmly.

…

The following spring I wrote Bowles from Paris, asking what I could bring him when I returned to Tangier. “Kellogg’s Corn Flakes,” he wrote back on a postcard.

I remembered his telling me how hard it was to get the American Kellogg’s cornflakes, that those he bought at the tiny European market in Tangier were made in Germany and tasted nowhere near the ones he loved. I went to Fauchon near the Madeleine and bought two large boxes, flown in from the U.S., and carried them with me to Tangier that June, the second summer of our teaching together.

Perhaps because he was so pleased, later that month, after our teaching chores were done, Paul brought me to hear a trance musician play his deep reedy flute at the home of Paul’s old friends, a dying Frenchman and his wife.

Paul’s driver on call was a Moroccan with extremely long legs, whose djellaba rose above his ankles. We drove to Old Mountain, where in the colonial days the rich Europeans in their villas partied nonstop. We parked on an earthen side road and walked toward the house. Paul stopped to point out a small cottage that he had once rented. It stood on a cliff’s edge facing the Mediterranean, so that from his window, sky and sea merged into one vast blue slab. “That’s the cottage where I wrote Up Above the World,” he said.

“Oh. Because the cottage is so high up on the mountain here?”

“No,” he said smiling. “Twinkle, twinkle, little star. How I wonder what you are. Up above the world so high,” he said. I had seen him smoke kif but had never seen him high, perhaps because that was his natural condition, to stay quietly high and up above the world.

We walked farther until we were met by our host, a woman in her late fifties, who drew us into a circle of six seated on a knoll a few yards from the house. She was grief-stricken and could hardly speak. She asked Paul in English, “How does anyone ever get over this loss? How did you, with Jane?” Paul did not answer right away. He took her arm and finally said, “We survive.”

Her dying husband lay in a wide stone-and-glass tower about twelve feet high at the cliff’s edge facing the Mediterranean. His wife slid open a window to let the music in, to soothe him, along with the morphine, in his dying. Sitting cross-legged on the grass, the musician played away on his thick wooden flute. Very odd how after a while everything but the music started to melt away. Me, too, melting, until I was only an atmosphere without body, and only a weaving low woody sound was left of the world.

…

III.

In many ways I began this pilgrimage of mine back in the Mississippi of my childhood when I was a gay man aborning - all body and atmosphere - as an orphaned sissy seeking certainty in such an uncertain world in the solace of the sentences I found I could conjure and, by doing so, felt conjured instead by them because they were telling me I was a writer. They still do. The other night as some of the young Moroccans on the terrace were trying to teach me the sounds to make within the phonetic constructs of their Arabic dialects which I could not quite master I told them it was all just too alien to me, too difficult. “What kind of sounds are not?” I was asked. “The sounds I make in silence,” I said. “That’s what writing is finally - sounds made in silence.” I was then looked at the way the adults could look at me when I was that sissy child trying to find a sense of certainty in the world. “What kind of creature is this?” was the look on those old Mississippi faces as it was too on the young Tangier ones.

Part of my pilgrimage since my childhood in Mississippi has always been the navigation it takes to discover the subjective goodness in what we consider the objectively bad in those we love or adore and to whom we are so instinctively drawn. Is it the goodness that draws us to them or the badness we uncover or that they so proudly at some point put on display? I have written about such a navigation in my two memoirs, Mississippi Sissy and I Left It on the Mountain, when I delved into the racism of those who raised me, but here in Tangier I have experienced it yet again when I have seen on the social media account of one of my new friends here - whom I, yes, adore - some things that have shocked me about what can only be termed his hatred of Israelis. One such post had a photo of young Israeli children under an Israeli flag with the caption written beneath it claiming they were the only children worth killing.

I should not have to write this. But here in Tangier I do, and feel profoundly sad about it. I have to write it. This: Every child has worth and no child is “worthy” of such a thing, or even such a thought.

I have often been accused by both sides in the conflict in the Middle East of lacking sufficient support for or opposition against each as I have sought balance and empathy in my attitude about the atrocities perpetrated by both sides. Moreover, that frightened Mississippi child I carry within me to this day - the one who had to navigate loving those who harbored bigotries within them - sees all children as worthy of life and respect before their innocence can be curdled by a call to calibrate their own navigations of the world with hatreds and distrust which just makes it even more dangerous, more deranged.

When I saw my new friend again who wrote that social media post he was still as sweet and nice and lovely to me as he’d ever been and yet I had to accept all that from him with a new kind of knowledge about him - and about myself as well since I still felt so drawn to him physically. He is, to me, quite beautiful. I also - this is the troubling part - felt still drawn to him in ways that aren’t physical, but are emotionally felt. How was my attraction still possible? Was this a dangerous form of derangement itself? Does it all stem from my having found a way to love those who raised me even though they spewed the n-word with abandon? Ahhh … Abandon. The word that haunts my life. In some way I can never abandon that abandoned child - an orphaned sissy who has felt my whole outcast existence a sense of unworthiness - whose navigation of this life, this pilgrimage was first built on the love of objectively bad people (if one believes bigots are bad) but who had goodness in them, deep, deep wells of it. It is the root conundrum from which my incongruous life continues to grow from Mississippi to Morocco in - another incongruity - unexpected but predictable ways.

I wanted to delve into some of this with a fellow Mississippian, the bibliophile and gallerist and aesthete Jane Stubbs who is from Natchez. She is also here in Tangier helping to organize the moving of the library of the American Legation to its annex while a refurbishing is being done to its rooms back at the Legation - or a “resuscitation” as she calls it. Her assistant is a young Muslim Moroccan man named Ali, who is in the above photo with her. They have bonded in their affection for each other and even in their differences. I wanted to talk to them about how they have navigated their friendship with such grace.

Jane, how does Tangier compare to Natchez, Mississippi?

It’s a place I love. It’s an eccentric small-town in a rather larger town. It reminds me very much of Mississippi and Natchez in its way with its different ages mixing at parties and none of the kind of age segregation of New York. I first came here in 2001. I was invited by a friend to come for a couple of weeks and just loved it. At that point , the drive into Tangier was the wildest thing. There were these red and green lights that came across the boulevard as one drove in from the airport as far as the eye could see. It was like Christmas …

In a Muslim country. There is certainly an alluring duality about this place. I love its incongruity. Hell, I love all incongruity. My life is based on it.

It just seemed like a magical place to me. I fell in love with it.

What’s it been like to work with Jane, Ali?

I have had the experience to learn a lot from her - how to fix books and read them apparently.

Were you a reader before you met Jane?

Ali is not the bookish sort.

You want to be a fighter of some sort. Is that right, Ali?

I am trying to punch people for a living. It’s mixed martial arts. There are judges and one is awarded points. It’s very regulated.

What appeals to you about it? I think you’re religious so is it its ritualistic aspects?

It’s because when I go there, there is a fear in me. The more I’m afraid, the more I am alive because I know I want to save my life.

That’s more philosophical than pugilistic.

It’s like a form of art.

What was your attitude about Americans before you met Jane and began to work with her?

I had a perception about them that they were fat and they could only speak English and they are not very educated.

You sound like you just described a Trump voter.

But since I met Jane there has been a lot of change in my attitude. Whatever subject I talk to her about she has something to say about it and knows about it - no matter what country we are talking about. She changed my perception of Americans. We are best friends some people might say.

And how has he changed your perceptions, Jane? You two could not be more different and yet you are very bonded.

We could not be more different. We have developed a wonderful friendship, and I have loved that. I have learned so much about Morocco that I did not know through my friendship with Ali. I have been to visit his family. He had an illness at one point and we went to different clinics and hospitals. That was intense. When he was so ill, all kinds of work boundaries just fell away.

There is an intimacy about caring for someone who is ill. It sounds more like family in its way than friendship.

Yeah, I took Jane to my home. Boundaries are not so much a thing here as they are in America. My first day with her I was telling her that she had to come meet my family because they would love her.

Do you have children, Jane?

I don’t.

So is there a maternal aspect to your friendship with Ali? He could be your child.

Or even a grandchild - as he has pointed out to me. I do feel very, very protective of him in the way I think that I would if I had children.

You grew up in what religion, Jane?

Episcopalian.

As an Episcopalian woman sharing an office with a young Muslim man, do you talk about religion?

All the time.

Ali?

And I beat her to the punch every time. I’m trying to convert her.

Hmm. More talk of punches. Any chance of that, Jane? A conversion to Islam?

He’s not going to have good luck with that. The Episcopalians I grew up with in Natchez made very few demands.

Other than about the dryness of their martinis.

Yes, it was always just cocktail time. And it’s never cocktail time in the Muslim religion. I have learned so much about Islam from Ali even though I had read a small Penguin edition of the Koran which obviously didn’t include everything.

Does it make you uncomfortable, Ali, that I am so openly gay?

I’ve been talking to Jane about this. When I see a foreigner who’s gay, I don’t care. It’s their thing. But when I see Moroccan and he’s gay, I feel he brought shame to Moroccans somehow. It’s deep down. I’m not going to lie about it. It’s a nationality thing. Because in Morocco they’re supposed to be strong men.

Let me beat you to the punch: You can be a strong man and be gay.

It’s very drilled into me. But I don’t care, to be honest.

Jane, were you an influence in this regard?

He has learned all sorts of things. He is here now in this environment where so many of the things he had thought are being rattled.

Ali?

I don’t mind gay people but I mind gay people who make it their personality.

But when I first met you, you made it very clear to me that you are straight. So don’t make it your personality either.

Well, yeah. I guess we should make some boundaries that you Americans like so much. To be honest, it was confusing to me at the beginning because all the people who have been treating me well and giving me opportunities are gay men. I was like, okay, I am supposed to believe that they are bad and they are harmful but all the good things I’ve gotten from life are because of these gay men.

So maybe Allah is teaching you a lesson by having your path intersect so positively with gay men.

Probably.

Jane?

Allah is teaching him so many lessons.

And us.

IV.

At some point in the night I had this dream. Or was it possible that I was partially awake, and was only remembering the dream? As usual the Muslim call to prayer had pried my dreams from me a bit after 5 a.m. and I lay in my tiny room in the Dar Gara hostel in the Medina here in Tangier listening to its blasted echoes all around me. Was this call itself what had been in my dream or was there another one now embedded in my subconscious? Half asleep, half awake I had been only moments before stuck in a crowd at a fashion show as a Muslim woman covered with her burka and holding her small daughter’s hand came up to me in a worried state and told me that she had to find a place to pray but had no idea where that would be as the call to prayer continued and on the runway the models paraded to it. I asked if I could take her hand and was given permission and she came with me as I tried to navigate the crowd in an attempt to find a safe quiet place where she could pray in solitude. But I couldn’t find it. That is my recurring dream: trying to find someplace I cannot find. I can never arrive at where I am going. There are always obstacles. But I am usually alone. For the first time I can recall, I had someone else by the hand trying to find the place for her and not for me. Suddenly, finally the call to prayer ceased. I lay for a few minutes marveling at the dream - and now the silence, the utter silence - and once again fell awake in Tangier.