THE MYSTERIES OF IAN

REMEMBERING MY FRIEND, IAN FALCONER

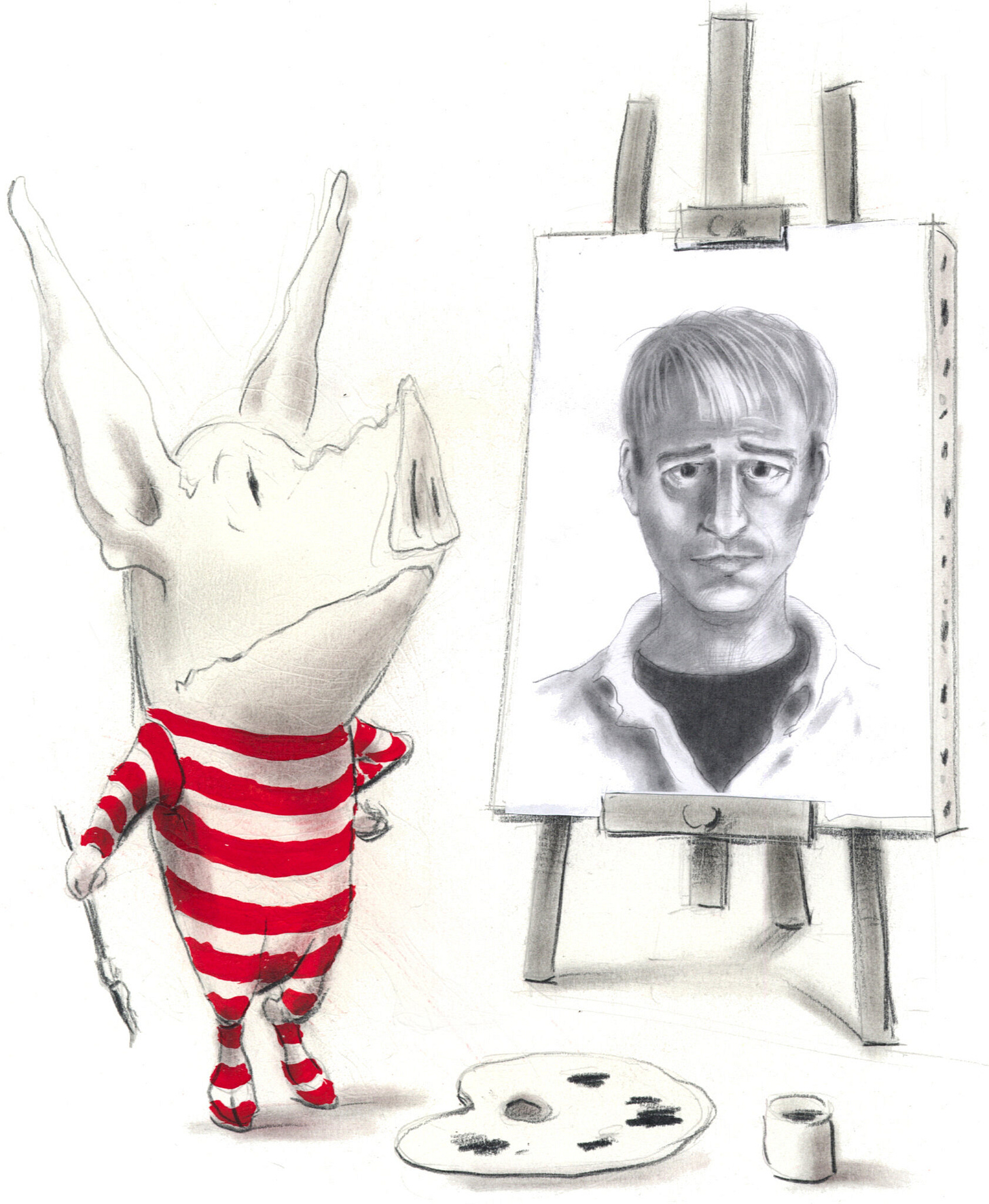

(Above: the illustration that Ian Falconer did for The New York Times when he agreed to answer some questions for its Book Review’s “By the Book” column which I am reprinting below in his memory. I love this illustration because it gets at Ian’s knowing whimsy. His famous Olivia has done his portrait but it is not quite right, just a bit off, and even the portrait is “commenting” on its not being spot-on. But being spot-on never interested Ian. He left room to ruminate. His children’s books were never condescending. They were childlike yet deeply sophisticated. They acknowledged the wariness embedded in childhood wonder before it grows up and wanders into the wearying room where rigor replaces rumination, where “wrong” alas has a “rightful” place, where quotation marks become quotidian, and questions much too quaint. He himself has “left the room” much too soon. I will ruminate on that the rest of my own life - and never quaintly question why. I loved the guy.)

(Above: an illustration by Maurice Sendak for his 1967 book, Higglety Pigglety Pop!: or There Must Be More to Life. It was Ian’s favorite children’s book.)

This past weekend there was a memorial dinner for children’s book author and illustrator, set and costume designer, artist, brother, son, uncle, and friend of so many Ian Falconer. It was held at the New York Yacht Club on Saturday. He died almost two months ago. I had just arrived here in Paris for my two-month stay - I have one more week to go - and came home from a concert around the block from me here in the Eighth Arrondissement to the news of his death. This is some of what I posted on Facebook the next day:

“I came home last night to my place here in Paris after attending a concert by pianist Maurizio Baglini playing Liszt's transcription of Beethoven's No. 9 to the news that one of my oldest friends, Ian Falconer, had died at the age of 63 surrounded by his family and a few other friends. I was already deeply moved by having experienced the Liszt transcription of Beethoven but the joy turned into an ode to grief as I sat in a daze and actually talked aloud to Ian believing the dead can hear us. I hope he had also been sitting beside me earlier at Gaveau Hall and hearing the Beethoven and sharing in the sublimity of my joy before surfacing later as my grief. He created such joy himself in the world with his art and his costume and set designs for ballets and operas and his Olivia books and his last one Two Dogs. He had a difficult last few years. I trust whatever death is it is not painful and he is free of that: human pain. Last night's concert felt healing to me so maybe he really was sitting beside me and what I was feeling was not my own healing but the hope of his.

“Indeed, feeling the healing of others is a way that we each can heal ourselves. Maybe that is what healing is, one vast feeling that we all finally feel a part of that has nothing really to do with ourselves but with some greater consciousness we can only know once we shed this one. Ian would be rolling his eyes at all that. ‘Come on, Kev,’ he'd say, then crack wise because woven into his knowing whimsey as an artist was his wisdom. The term ‘old soul’ has become hoary, tatty. But Ian always was. Even as a 20-something he was crotchety. But he was never cruel. There was kindness in him. And beauty. And a belief in both. When I was still an actor - that's how far we go back - I once left the city for several months to play Alan Strang in a production of Equus and Ian needed a place to stay, so I even gave him my little 6th floor walk-up on Bleecker and Sixth to crash in for those months. We were that kind of friends. I loved him.

“I will never forget the first time I laid eyes on him and his then boyfriend, Wilson Kidde, over 40 years ago. I was sitting with Henry Geldzahler - and I think David Hockney - at the Ninth Circle in the West Village when we saw them walk in on a trip to the city from where they were attending college at Princeton. Of maybe only Wilson was. That bit is hazy. But part of my role in those years I was mentored by Henry was to fetch the fetching. So I made a beeline for Wilson and Ian and brought them back to introduce them and bring them into Henry's art world fold where we all learned to be aesthetes and, instead of judgmental, discerning. Cut out of the herd myself, I helped cut them out of it. He and Wilson became friends - Ian and I often more than that when we were in the mood. It was a heady time not only because it was the time of our youth but also because it was when we became a part of an ‘our crowd’ crowd. There is a French term - jeunesse dorée - and we were. Ian with his looks and locks of blonde hair really was. He was golden. The world is less so without him in it.”

###

Part of being in “our crowd” was to head up to Rhinebeck at times to visit the farm of art dealer and collector Stephen Mazoh, who died himself from complications from Parkinson’s Disease only two months before Ian died. Ian and I would sigh twiddling our thumbs by a Twombly when making those first visits to Stephen’s with Henry Geldzahler, read by the fireplace or be more sneakily randy in the middle of the night on the floor in front of it, or wander the grounds admiring sculptures just beginning to be carefully placed there just as he and I - and other young artful types - were being carefully placed in such a setting ourselves. One day as we were lying on the grass staring up at the sky, I thought I had spotted a hawk but repurposed it for our narrative that day as a falcon since I always thought they were rather the same thing, in the way that I merged the kind of friendship I felt for Ian with a longing for another kind of love. Henry once told me that my obvious crush on Ian made me a “fauconier.” A few years later, I actually read in a narrative written by one of my favorite writers, Michael Chabon, in his novel The Mysteries of Pittsburgh, a replica of the conversation that Ian and I had had that day.

“Love is like falconry. Don’t you think that’s true, Cleveland?” wrote Chabon.

“Never say love is like anything” Chabon has Cleveland say in return. “It isn’t.”

As I was walking around Paris on Saturday thinking of the memorial dinner I was missing for Ian I remembered our almost identical conversation.

“Henry says I’m a falconer myself,” I said to Ian as a way to confess my feelings. “Love is sort of like falconry, don’t you think.”

We watched the bird soar, swoop, disappear, return. The sun moved a bit and the art next to which we lay offered us now its sharpened shade. “Love is not like anything,” he said. “A hawk is like a falcon. But love is not, Kev. That’s a hawk.”

And in that moment I fell more deeply in love with Ian as a friend. In some way I have been befriended anew by him in his death. He is the sharpened shade in which I have lived these last two months. In Sendak’s Higglety Pigglety Pop!: or There Must Be More to Life, the lead character, Jennie, who is a Sealyham terrier, sets off on a pilgrimage to Castle Yonder. I like to think of Ian there now with her and their buddy Olivia born of her and with Sendak and Mazoh and Henry and maybe lots of “maybes” where quotation marks are no longer quotidian and the first question asked is, “Wasn’t this place supposed to be more quaint?” And the next thing said is, “Thank God it’s not.”

“Let’s not talk about God,” says the caption beneath Ian, who is bemused to be drawn into the picture of the place.

And then he is drawn drawing himself drawing the others, a yawning Yonder replete with replication, revision, renewal, an infinite whimsical knowingness, a falconry of mystery. He soars, swoops, disappears. He does not return.

(Above: Ian photographed by Patrick McMullan.)

Here is that interview:

What book is on your night stand now?

I’ve just got Jim Holt’s “Why Does the World Exist?,” which is marvelous and, given the subject, very readable. I’ve been working, and when I work I generally read things that are short and distracting, so I also have (next to the bed) “A Mencken Chrestomathy” and (next to the potty) “The Oxford Book of Humorous Prose,” wonderfully edited by Frank Muir — everyone should have a copy — and “All in One Basket,” by Deborah Mitford, Dowager Duchess of Devonshire. It has six pages devoted to the tiara which are worth the price of the book.

Any literary genre you simply can’t be bothered with?

Vampires. Definitely vampires.

What was the last book to make you cry?

Normally I don’t cry at books. I’ll tear up watching a State Farm commercial but am more circumspect with the printed page. I do remember, about age 13, “David Copperfield” and the powerful adolescent feelings that swelled reading of Steerforth’s rotten treatment of little Emily.

The last book that made you laugh?

I read a lot of humor. I laugh all the time.

The last book that made you furious?

Books don’t make me furious. Career politicians make me furious.

Name a book you just couldn’t finish.

Oh, gosh. “The Eustace Diamonds.” I always get lost trying to read Trollope. I’m sure I have many books with untouched pages after the break in the spine.

What were your favorite books as a child?

Fairly obvious choices. Dr. Seuss’ “The Cat in the Hat” and “The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins”; Maurice Sendak’s “Where the Wild Things Are,” “Nutshell Library” and “Higglety Pigglety Pop!” ( a great favorite); William Steig’s “Sylvester and the Magic Pebble.”

What makes a good children’s book?

That’s a bloody good question. O.K., if I had to say one thing, it would be to not underestimate your audience. Children will figure things out; it’s what they do best — sorting out the world.

What’s the best book by an illustrator you’ve ever read?

I’d have to say “Higglety Pigglety Pop!” The story is sort of slow and moody, but very funny, and the monochrome drawings beautiful.

Of the New Yorker covers you’ve illustrated, which do you like the best?

There are a couple of Valentine’s Day covers I’m proud of, and I always do well on Halloween. I think my all-round favorite is a cover I did for Miss America. A row of all-American, blond, cookie-cutter beauties showing off their perfect pearlies, and a snarling, raven-haired Miss New York in the middle, like a bad tooth. I’m also very pleased with my latest cover — a global warming theme featuring Santa Claus.

You often work as a theater designer. Do you enjoy reading plays? Any recent favorites?

Most theater work I’ve done has been ballet, opera or musical. I get a bit lost reading plays cold. The descriptive glue interspersing the dialogue is so pared down (“H. crosses stage left. Spies L.M. Mock horror”), that I can’t really see a picture.

If you could meet any writer, dead or alive, who would it be? What would you want to know?

An answer to that could be its own book. Socrates, I’m sure, could really hold a dinner table. I’ll bet Suetonius could keep your attention too. (“Oh my dear! Next to Galba, Caligula was an absolute nun!”) I’ll stop here.

You’re holding a literary dinner party and inviting three writers. Who’s on the list?

If you had combined the last two questions — “You’re organizing a literary dinner, and you could invite three dead writers . . . ” — you could have a lot of fun. First I’d ask Shakespeare, Marlowe and the Earl of Oxford and get that tiresome question out of the way for good.

Do you have a favorite book about pigs?

“Animal Farm.”

Any plans to write a book for grown-ups?

But I do write for grown-ups.

If you could give one piece of advice to aspiring artists and illustrators. . . .

I would say study life drawing as much as you can. It will inform your illustration in so many ways. I can’t stress this enough.

Marvelous, Kevin. We're at that time in our lives when we're unlucky that friends die and we grieve and miss them, but lucky that we can remember them as they were when we met them. Remembering is a gift, and using your memory by writing is another kind of gift to ourselves. Your friend Ian would be thrilled right down to his socks that you remember him as you do.