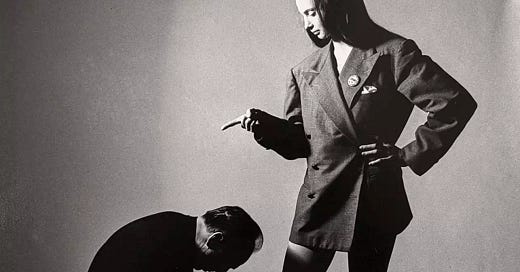

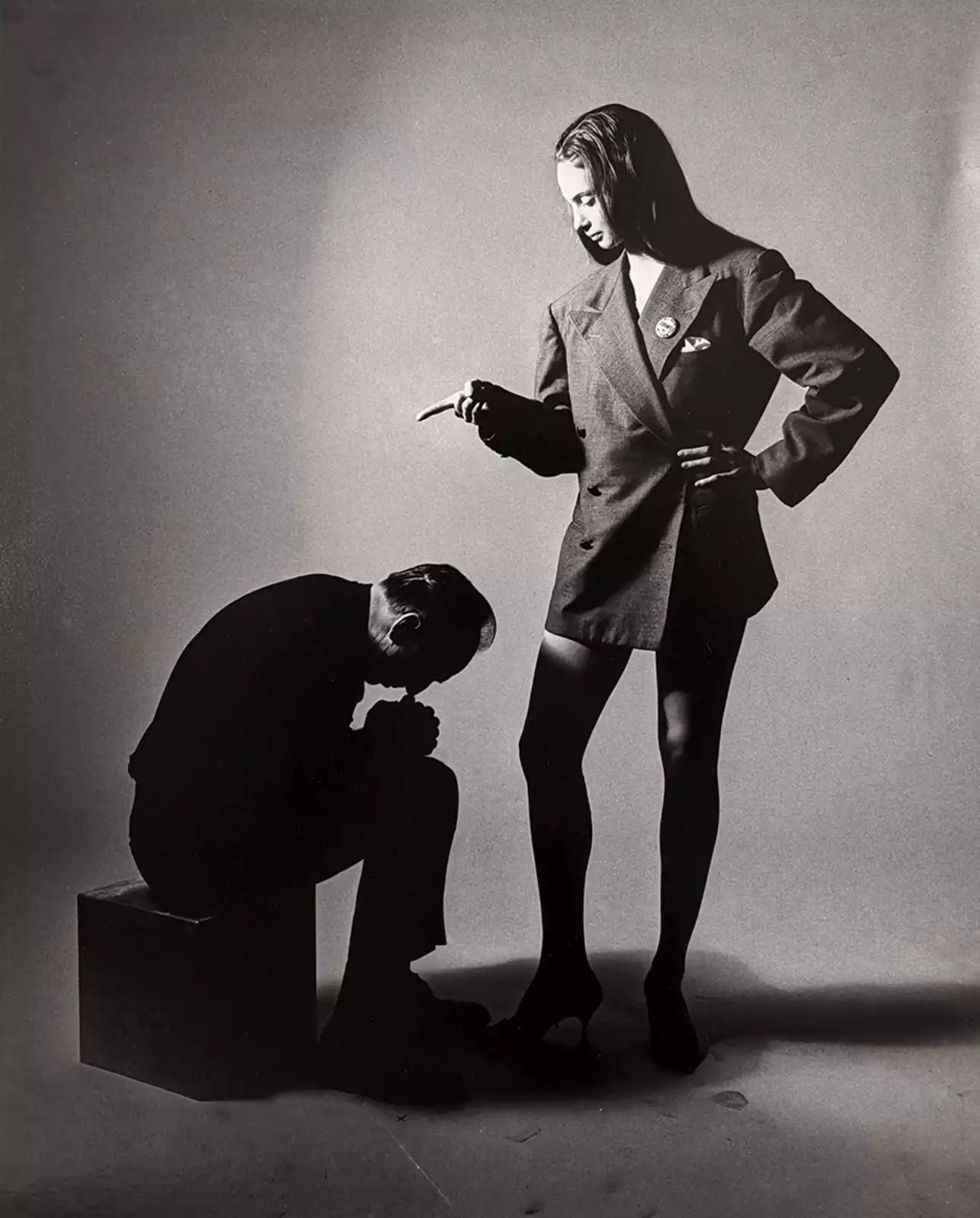

(Above: George Balanchine and Suzanne Farrell. Photograph by Bert Stern. Vogue, 1967.)

People often ask me the question in the title above. I once had an answer at the ready that was, as usual, self-deprecating and yet captured the visceral allure ballet held (and still holds) for me. “I don’t know much about ballet. I’m not schooled in it. I just know how it makes me feel,” I’d say. “It’s like having amazing sex with someone - the kind when you feel as if the top of your head is about to come off - and then afterward you realize you don’t know the person’s last name. I don’t know ballet’s last name but sex with it is the best I’ve ever had.” Yes, there is a physical sensation I have when witnessing its physicality, its athleticism - a carnality that cannot be denied - but it goes deeper than that and has over the decades seeped into my soul, reminding me that I even have one when I have spiritually had my doubts since it was ballet, when I was a boy, which let me know that I just might have one after all. It lifts my spirits as if it is partnering me, its hands around something that hands should be incapable of holding for I feel its fingers on what is ephemeral about me; it imbues my emotions with its artful flesh. Most of all, it makes me less sad even though it can leave me in tears. That’s it on its most basic level: it taught me how to cry without the need for sorrow.

Ballet did not dry my tears - it knew such an attempt was futile - but drew them out of me in a new way. The second time it happened was over 40 years ago when I walked into the New York State Theater at Lincoln Center to see New York City Ballet for the first time. I am newly astonished each time it still does here in London now at the Royal Opera House, the home of the Royal Ballet, or at Sadler’s Wells or London Coliseum where I have seen the English National Ballet. Since October, I have seen the Royal Ballet’s Mayerling and The Sleeping Beauty more than once, and marveled at its production of Crystal Pite’s Light of Passage. I also attended its gala Diamond Celebration evening with new and old works by Pam Tanowitz, Joseph Toonga Valentino Zucchetti, Christopher Wheeldon, George Balanchine, Frederick Ashton, and Kenneth MacMillan. I liked the English National Ballet’s Swan Lake even better than the Royal Ballet’s and have equally marveled at its way with choreography by William Forsythe. And I will never forget the Royal’s Matthew Ball - also brilliant when he danced Mayerling - and Joseph Sissens dancing Wheeldon’s duet Us at the Coliseum as part of the Men in Motion program produced by dancer Ivan Putrov. To be astonished at 67 - I might as well own it since my birthday is next month - is the gift too ballet unwraps within me. It renews with the sinews of its art the parts of me aged with cynicism and sin and the gibbous gait of hobbled hope. I find it wondrous, and doing so makes a place for more wonder to wander gracefully as well into my life. It gives me my gait back. It gives hope back its.

I have been on a search for grace in any form since I became feral with sorrow after the consecutive deaths of my parents in 1963 and 1964, my father having been killed in an automobile accident and my mother having died of esophageal cancer, each in their early 30s. I really do think I was maddened by grief, the kind with which no grownup can grapple for it needs a childhood to churn into its dark magic. Outwardly I was a mannered little sissy clinging to good manners; inside I was a wild angry urchin orphaned of everything but the desire to destroy what was left in my wake. I knew people looked on me as some sort of creature, demonized if not demonic, since I refused to hide being a sissy and even flaunted it. Conversely, there was a brutishness within me that the sissiness camouflaged which was also what enabled me to be brave enough to weaponize my being a sissy. I hadn’t seen a plié yet, but I knew how to wield my pliable wrists.

It was the year after both parents died when I first became aware of ballet. Initially, it put some joy back into my life. The first time I remember laughing after Mommy and Daddy died was one morning watching I Love Lucy when Lucille Ball took a ballet class with Mary Wickes as her instructor. Later that year, I faked a stomach ache one Sunday night so I wouldn’t have to go to evening church services. I curled up in front of the black and white television to take in the acts on The Ed Sullivan Show, so satisfied with myself for having gotten away with faking an illness then feeling guilty not for skipping church but for disrespecting illness to do it since illness had been what had taken my mama from me. That night on Sullivan, Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev performed a pas de deux from Swan Lake. There was nothing Ball-at-the-ballet-barre slapstick about it. It was indeed something I had never seen before and need an “indeed” in a sentence to describe whatever it was. That Sunday night was the first time I cried my ballet tears, shedding them at a kind of beauty that was unknown to me trapped as I was in a world where wonder had seemed to die along with my parents and left me gracelessly lost in the plodding ugliness of grief. I wasn’t crying from sadness finally but at witnessing the manifestation of longing in that Swan Lake pas de deux, of being something that you are and that you are not at the very same time, a swan and a woman, a well-behaved little sissy and a child feral with an inside sorrow. I also longed there in 1965 before that television set to know more about such beauty which replaced the longing I had had for so many months not to be so damn sad and secretly angry and stuck out in the country in Mississippi where my grandparents, who took me in with my brother and sister, lived their ballet-less lives. Yet there I was alone in their living room - mine now, ours - at the end of a pas de deux fixated on Fonteyn’s black and white foot as it vibrated and quivered and quieted ironically at the very same time the frenzy inside me it was mirroring. I am sure there is a term for such un pied tremblant, but I still don’t know ballet’s last name. What I do know is that a recognition swept over me at that moment and a bonding with ballet itself because I recognized in the vibration of that foot the way my mirrored soul felt inside of me. “Soul” was a church term I did know about, but it never meant anything to me until I saw Fonteyn’s foot. That was my soul. That was how it felt inside, and in that moment its beautiful agitation reshaped and replaced the anger harbored there. Church never gave me that spiritual definition, that salvation. Fonteyn’s foot did.

When I arrived in New York City at the age of 19 to attend Juilliard’s Drama Division, I was welcomed into a fold of older balletomanes who were part of Jerry Robbins’s nest of eggheads and who miraculously spotted a kindred spirit in me - or maybe their own longing had to do with my more earthly pull for them. None of them ever made a pass at me, however, in all those nights they ushered me into the New York State Theater, their own church, their own temple, to experience New York City Ballet of the 1970s and 1980s. I was introduced to Jerry and brought into his world of lofts and lofty dinners and then introduced to his works as well as the “ballet-is-woman” genius of Balanchine. Both Jerry and Mr. B. were flawed men but they were not false gods. I too began my worshipful years attending NYCB which had one distinctive quality to which I deeply responded: it mostly had no need for narrative. It was such a spiritual and emotional relief that any intellectual challenge it presented to me as I entered my 20s was offset by this newfound balance ballet put into my life for I had, up until my early years witnessing NYCB, steeped myself in narrative as a survival instinct. Even before I lay in front of the black and white television that Sunday night and experienced the deliverance of that Swan Lake pas de deux, I had become a character in the narrative of my own life as a way of separating myself from the sorrow of it. My first act of being an outsider was to step outside my own life at the age of 8 and to create a narrative self. I am not sure if I were born a writer and thus survived the trauma or my childhood or I became a writer in order to survive it. But I was a writer before I ever wrote a word. Narrative - its separate power - was what I deployed to battle back at life. It was the lack of any need for narrative that was ballet’s hold on me in my early years of attending NYCB. I even developed an aversion to story ballet. It wasn’t until I began to spend so much time at the Royal Opera House watching the Royal Ballet that I became a fan of Kenneth MacMillan’s plotted full-length works. His Manon was the first story-driven ballet that moved me. I have now seen it over and over. New York City Ballet healed me of my narrative need. The Royal Ballet healed narrative itself for me.

And then there was Suzanne Farrell. She was returning to NYCB in 1975, which was the year I moved to Manhattan to attend Juilliard. Seeing Farrell onstage in the “Diamonds” section of Balanchine’s Jewels was a transcendent moment in my life as all feral elements that still existed inside me fell away. Ever since the trauma of my parents’ deaths, my life had been imbued with a feeling of disorder. Watching Farrell for the first time felt not like order returning to my side, but instead more like the establishing of a New Order. Sophisticated. Disciplined. And within it, something other than personal sadness could be deeply felt: the melancholic magnificent that great art and great artists can inculcate into the lives of those who care to open themselves to it and them, a pensive resolve purer than any other survival technique I had ever deployed on my own. Oh, sure, I noticed Peter Martins’s butt as he partnered her, but I kept returning to Farrell’s body forming spacial art. I have tried to move through my life in a semblance of its evanescent grace ever since. Balanchine described her in the “Diamonds” section of Jewels as a “whale in her own ocean,” and there was a sense of seeing someone swim within a new context, an unseen watery flow of air and waves and, yes, this word again: wonder. Arlene Croce, the dance critic for The New Yorker from 1973 to 1998, wrote of Farrell in this ballet, “Your eyes gorge on her variety, your heart stops at the brink of every precipice. She, however, sails calmly out into space and returns as if the danger did not exist … Farrell’s style in Diamonds is based on risk; she is almost always off balance and always secure … Of course, the autonomy of the ballerina is an illusion, but Farrell’s is the extremest form of this illusion we have yet seen, and it makes Diamonds a riveting spectacle about the freest woman alive.”

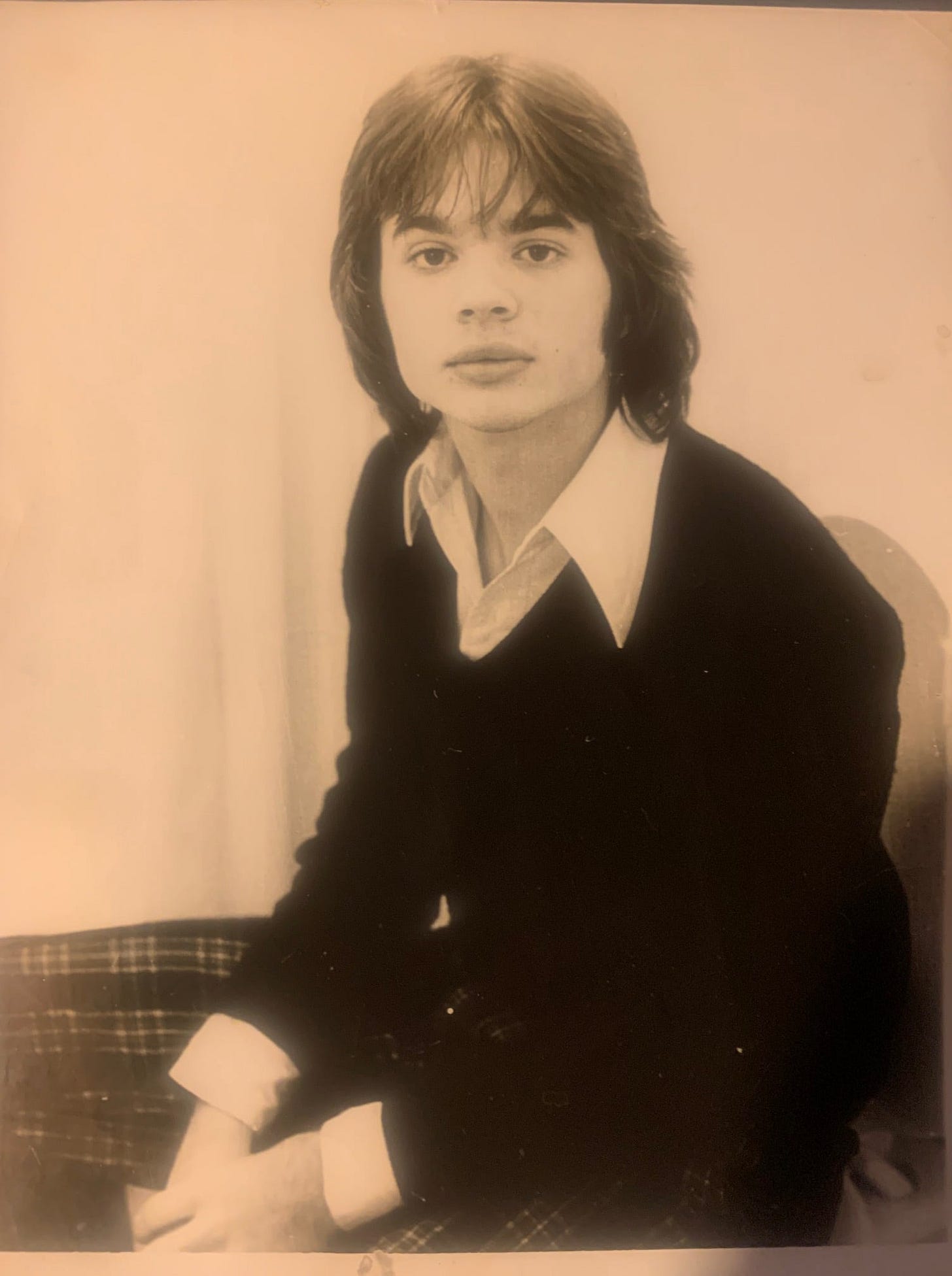

(Above: A photo of me at 17, two years before I moved to New York to attend Juilliard’s Drama Division and discovered New York City Ballet across the way at Lincoln Center.)

When I was a teenager - and during those first years in New York City - I was told over and over that I reminded others of Nureyev. I loved being told that because I’d remember lying on that Mississippi floor on a Sunday night and seeing him with Margot Fonteyn. Maybe the bonding with her was combined with a melding with him. The melding continued when I later met his young French boyfriend who was visiting him at his place in The Dakota and embarked on an affair with him. When I visited Paris several months later, the boy had returned to their apartment there alone. He invited me over and we made love in Nureyev’s bed which is fitting since I have always lived a life just outside the frame of fame. I remember the boy’s first name but I can’t recall his last one - which too is fitting since I have come to like not knowing ballet’s and the mysterious slightly illicit allure it can still have for me because of that, this wordless art form that captured this wordsmith’s broken heart. That is finally the greatest irony of all about my love of ballet, its wordlessness. There is a practicality to that though since I can go to a ballet anywhere in the world and not worry about knowing a country’s language. But it is poetic as well - even in the embedded way poetry is rhythmically so. There is the musicality of the art form along with its movement. Dance sentences us to sight and sound; language just might be the one thing for which it does not long. It is complete without it.

That Nureyev quality that others once saw in me was not just about homoerotic allure, but more deeply about setting out as Nureyev had on a pilgrimage toward himself by leaving all that he had ever known just as I did when I was only 19 to move to New York City from Mississippi and just as I’ve done now in a more profound way by shedding almost all my possessions as I continue on a lifelong choreographed search for who I really am. I have told people I am doing this because “I have one more chapter left in me,” proving that I am still creating a narrative in order to live a life. Croce called Farrell in Jewels the freest woman alive. Nureyev’s allure for me has always been the bravery it took for him to leave everything he knew behind in his great leap toward freedom and artistic renewal. I discovered long ago that the way to survive was not only to live a narrative, but also to set-out over and over within it to seek one’s own version of that. Fonteyn’s foot was my soul manifested. But my true north was Nureyev’s nerve.

Ballet righted my writerly life.

It rights it still.

MyKen’s 2nd wife - Diana Byer - founded the New York Theater Ballet; I know you don’t know this … but Ken - my Ken …my glorious Ken… helped build that Ballet company from the ground up in their loft & then… helped finance that company. My husband is quite the hero. But, Diana, is quite the Goddess SHEro!

Bravo!